Gold was called ‘Semen of the Sun’ and ‘Sweat of the Sun’ by ancient pre-Columbian South American cultures but on that continent, where gold was abundantly available, it had no material value intrinsic. However, it has great spiritual significance as its malleable yet indestructible properties are considered to be ‘from’ the Sun. Therefore, gold was considered a conduit to the Sun god. After being melted down and mixed with other metals to change color for various rituals, it was crafted into ornate offerings, masks, statues, and jewelry, which were then thrown. into sacred lakes and lagoons in large numbers.

On the other hand, in Western materialistic cultures, where achieving wealth in this life is considered more important than ensuring security in the next, gold is more sought after than any other. any other material thing – but it has no spiritual value. Fundamentally different views on gold led to global upheaval in the 16th century, when Spanish belligerents, flying the flag of God, arrived in South America and launched a brutal gold-gathering operation that is being led by a wave of genocide across the continent. Tens of millions of indigenous people were massacred.

The Muisca raft, representing the beginning of the new Zipa in Guatavita Lake, may be the origin of the legend of El Dorado. (Andrew Bertram/ CC BY SA 1.0 )

Rushing to find gold

Two and a half centuries later, gold-hungry Europeans were still running across America with the idea of finding gold. And it happened! The famous California Gold Rush began on January 24, 1848, when James W. Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California. This news attracted more than 300,000 prospectors to the state. At the beginning of the Gold Rush, it was truly the Wild West as no laws existed regarding ownership in gold mines. Thus, entire indigenous societies whose heritage dated back 13,000 years were attacked and driven from their ancestral lands by money-hungry gold hunters, known as “the forty-niners” (referring to 1849), who mined tens of billions of dollars worth of gold today, which led to enormous wealth for a few.

Panning for gold during the California Gold Rush. (Public domain)

On the other side of the Atlantic, on Scotland’s remote northeast coast, magical Strath Kildonan hugs the River Helmsdale as it flows southeast through the remote uplands towards the North Sea. Kildonan Burn is a small tributary of the River Helmsdale that flows from the foot of the “Irish Hill” and lies under a one-way road for about 10 miles (km) along the A897 from the village of Helmsdale. In 1818, a large nugget weighing “about 10 cents” was found in the Helmsdale River. It is thought to have been made into a ring that is now in the possession of the Sutherland family.

Scotland’s ‘Golden Town’

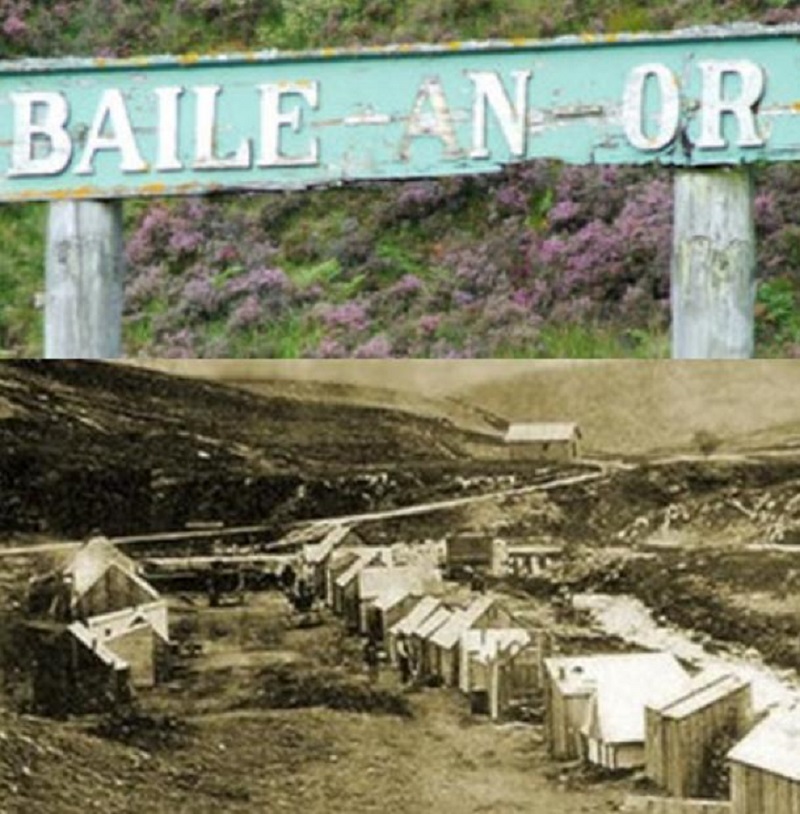

Fifty years later, in 1868, an ambitious prospector named Robert Gilchrist returned to Helmsdale from the Australian goldfields and received permission from the Duke of Sutherland to prospect for gold in the Helmsdale River. He continued to ‘discover gold in many places’, but concentrated most on the Suisgill and Kildonan fires. News of Gilchrist’s findings quickly became widely reported, attracting national interest. By April 1869, more than 600 prospectors had made their way to remote Strath Kildonan in the hope of making their fortune, which required an arduous 30-mile (km) hike from Golspie railway station. Two temporary settlements were established – a shanty town on the edge of Kildonan Burn at Baile an Or: Gaelic for Golden Town, and Carn na Buth, or Hill of the Tents, on the edge of Suisgill Burn.

Baile an Or: Gaelic for Golden Town. (Top: Author. Bottom: Free sharing)

Gold-filled gravel was removed from the burn margin and sifted into wooden grates. It is then rotated several times in the pan to separate the pebbles from the gold. Because gold panning was not an activity requiring special skill, the Scottish gold rush attracted a combination of both skilled miners from the fields of California and Australia as well as mechanical explorers. armed with hoes and hearts full of hope. A June 1869 edition of The Inverness Courier reported: “Mr. Wilson, a goldsmith of Inverness, bought thirty pounds worth of gold, five pence eightd in the early part of March, and purchased additional gold worth £193 at the end of the month.” In June, a drought enabled prospectors to strike at exposed gravel on the riverbed and ironically the price of gold, at its peak of £4.50 ( ) an ounce, plummeted down to 3.5 oz ($3.50) an ounce.

In late summer, the Duke of Sutherland began charging “£1 per month” ($ ) for prospecting licences, plus a 10% royalty on all (declared) gold found. This reduced the number of gold miners to around 200, however, falling gold prices coupled with decreasing find levels and better opportunities in the local herring fishery, meant that numbers dropped to about 50 by the fall. To further squeeze prospectors, the Duke was losing out on potential income from salmon fishermen and deer hunters, so in December he announced that “any prospecting for gold would terminated as of January 1, 1870.” The Strath Kildonan gold rush ended and Baile an Or was abandoned, still standing today, largely as it was when the prospectors left.

Photograph of Baile an Or taken by Alexander Johnston in 1869. (Suisgill)

You can try panning for gold

If you find yourself in the Scottish Highlands and want a truly ‘out there’ experience, then you simply need to visit the Helmsdale river valley and in particular the Gold Rush village of Baile-An-0r. The unpolluted, deep purple, peaty river is a hunting ground for wind-sheared hawks and a playground for flocks of cobalt blue dragonflies. Here, nature exists at an almost pristine level, with no managers, campsite attendants or thugs – just you and the great outdoors. You can camp for free in a tent, motorhome or caravan for up to 2 weeks a year and barbecues are welcome. I highly recommend giving gold panning a try, as not only does it give you the chance to explore for a few hours at a time, but it’s actually a great, sometimes back-aching, workout. Here are a few suggestions for the adventurers out there.

Goldpanners at the Kildonan fire, Scotland. (Les Harvey/ CC BY SA 2.0 )

Gold panning is restricted to the areas between the top of the stone bridge and the ford. Mineral separation equipment is limited to gold pans, sieves (hand sieves), spades and trowels, but gravel vacuums are permitted.

Digging must be done in the center and on both sides of the burn, avoiding bank erosion. Any holes must be filled for the safety of other users.

The gold mining rights are currently owned by the Suisgill Estate and the position regarding gold panning today is set out on their website.

You can learn more about the Strath Kildonan gold rush and see some gold at the Timespan Museum and Art Center in Helmsdale.

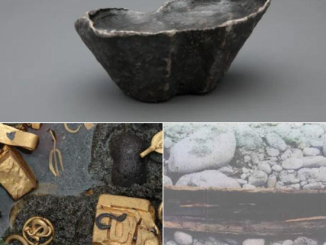

A nugget from Kildonan Burn, Helmsdale, Sutherland, Scotland. (mineral paradise)

Top image: gold panning at Kildonan. ( slains-castle ) Alluvial gold from Kildonan Burn, Helmsdale, Sutherland. (BGS Geological Heritage)