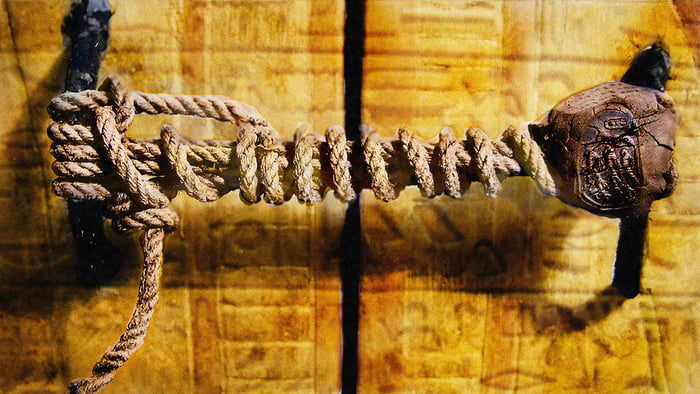

Tutankhamun’s unbroken rope seal

This is the rope seal securing the doors of Tutankhamun’s tomb, unbroken for more than 3200 years until shortly after Harry Burton took this photo in 1923. A description from National Geographic:

Still intact in 1923 after 32 centuries, rope secures the doors to the second of four nested shrines in Tutankhamun’s burial chamber. The necropolis seal — depicting captives on their knees and Anubis, the jackal god of the dead — remains unbroken, a sign that Tut’s mummy lies undisturbed inside.

How did the rope last for so long? Rare Historical Photos explains:

Rope is one of the fundamental human technologies. Archaeologists have found two-ply ropes going back 28,000 years. Egyptians were the first documented civilization to use specialized tools to make rope. One key why the rope lasted so long wasn’t the rope itself, it was the aridity of the air in the desert. It dries out and preserves things. Another key is oxygen deprivation. Tombs are sealed to the outside. Bacteria can break things down as long as they have oxygen, but then they effectively suffocate. It’s not uncommon to find rope, wooden carvings, cloth, organic dyes, etc. in Egyptian pyramids and tombs that wouldn’t have survived elsewhere in the world.

How was King Tut’s tomb discovered 100 years ago? Grit and luck

The 1922 discovery became a global media sensation—and captured the imagination of millions.

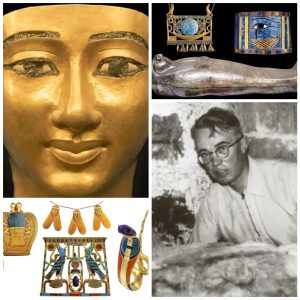

Lady Fiona Herbert, the eighth Countess of Carnarvon, turns the folio pages of a leatherbound guest book, pointing out the signatures of illustrious visitors who frequented her famous home a century ago. We are high in Highclere Castle, the grand country estate some 50 miles west of London that in recent years became the setting for the popular period drama Downton Abbey. Now every table, chair, and much of the floor in Lady Carnarvon’s small study is stacked with books and original documents from the 1920s: letters, diaries, and yellowed photographs mounted in albums or rolled up like ancient papyrus scrolls. The guest register contains the cast of characters for a book Lady Carnarvon is writing about her husband’s forebear, George Edward Stanhope Molyneux Herbert, the fifth Earl of Carnarvon. “The Fifth Earl,” as she refers to him, famously sponsored British archaeologist Howard Carter in his dogged search for the lost tomb of King Tutankhamun. Lord Carnarvon also hosted lavish parties at Highclere that brought together an eclectic mix of explorers, diplomats, socialites, and—a bit surprising for an English aristocrat—leaders of Egypt’s independence movement.

Lady Carnarvon stops at July 3, 1920, and introduces the guests as if she’d been at the soiree herself. “Here is Howard Carter, of course, who spent weeks here each summer planning the excavations with the Fifth Earl … British High Commissioner Lord Allenby … Alfred Duff Cooper and his beautiful wife, Lady Diana Cooper.” She indicates a noble who signs only one name, Carisbrooke—a grandson of Queen Victoria: “A minor member of the royal family, to give the gathering a little street cred.”

She points out a series of signatures, some in Arabic script. “And look there … Saad Zagloul, Adly Yeghen, and other fathers of the modern Egyptian state.” Zagloul, a national hero in Egypt, had been arrested and exiled for his opposition to British occupation. Yet here he was, hobnobbing with British bigwigs.

“I can see what he was doing, because I do it myself,” Lady Carnarvon says of the earl. “The Fifth Earl was putting people together informally, where they could develop a measure of personal trust, maybe even friendship, before negotiating a treaty or solving a political crisis.”

I notice that Zagloul signed his name next to Carter’s and wonder if they conversed about the fate of Egypt’s ancient treasures. Zagloul decried foreign control of Egyptian antiquities as a pernicious form of colonialism—an issue over which he would soon clash with Carter and the archaeologist’s blue-blooded benefactor.

Lord Carnarvon began spending winters on the Nile in 1903, on the advice of his doctor. He suffered congenitally poor health, made all the worse by a near-fatal car accident that left him with badly injured lungs. (An avid “automobilist,” Carnarvon owned one of the first cars in England.) Breathing Egypt’s desert air was, he said, like drinking champagne.

Soon Lord Carnarvon was relishing Egyptian antiquities as much as Egypt’s air. In 1907 he hired Carter to search for artifacts for his growing collection at Highclere and to supervise the excavations he was funding.

Carter had left England for Egypt at 17 with no formal training in archaeology but with marked talent as an artist. He developed a keen eye for artifacts and in 1899 was appointed one of two chief inspectors of antiquities in the Egyptian Antiquities Service.

Carter’s fortunes took a sharp turn in 1905, after what he called a “bad affray” with a group of French tourists. (They were drunk and abusive, Carter claimed, although he later admitted to having a “hot temper.”) To avoid a diplomatic incident, his superior told him to express his regrets. He refused, feeling that his only honorable option was to resign, which he did several months later.

Carter had been scratching out a living selling watercolors to well-heeled tourists when he was introduced to Lord Carnarvon two years later. The two men stood far apart in the social pecking order, but they shared a passion for ancient Egypt. Their partnership would lead to the discovery of a little-known boy king who had been laid to rest with a staggering store of treasures, then largely forgotten for more than 3,000 years. The find was one of archaeology’s greatest triumphs, offering the world a dazzling vision of ancient life on the Nile and instilling in modern Egyptians a new sense of national pride and self-determination.

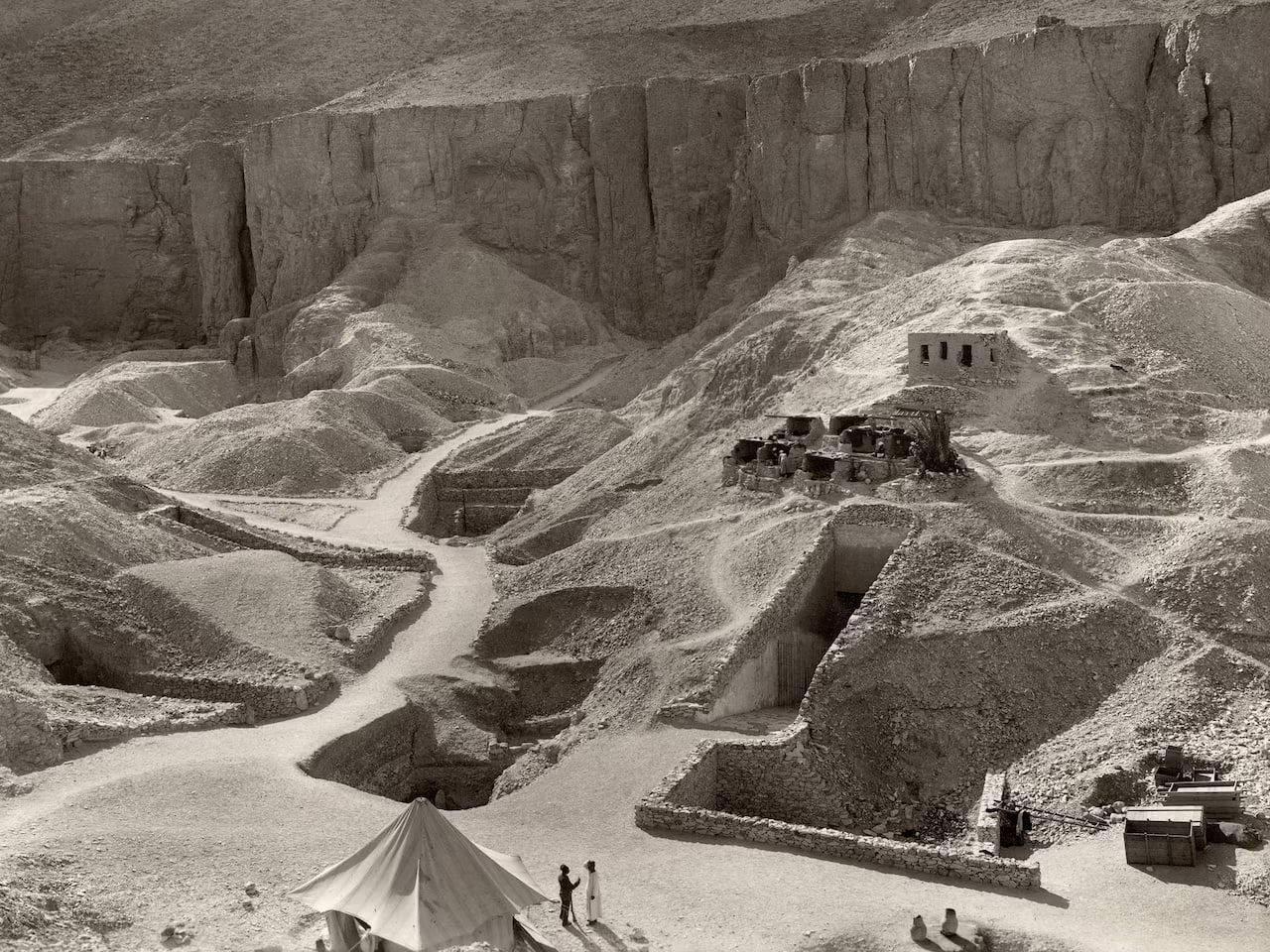

Important clues to the whereabouts of Tutankhamun’s tomb came to light in the early 1900s in the Valley of the Kings, a complex of rugged canyons across the Nile from modern Luxor, site of the ancient Egyptian capital of Thebes. Unlike earlier pharaohs who were interred in towering pyramids that became easy targets for looters, Theban royals were buried in tombs dug deep into the secluded valley’s rocky hillsides.

By the turn of the 20th century, the Theban necropolis was Egypt’s most productive and prized archaeological site. Excavations sponsored by Theodore Davis, an American businessman, produced a string of important discoveries. Among them were a few artifacts bearing the name of the mysterious Tutankhamun.

Carter had developed an intimate knowledge of the Valley of the Kings during his years as chief inspector. But before he and Lord Carnarvon could start digging there, they had to acquire the excavation permit, called a concession, which was jealously held by Davis.

Archaeologists and treasure hunters had been digging in the valley for decades, and many believed the heyday of discovery had come and gone. After years of funding successful excavations, Davis was coming to the same conclusion. “I fear the Valley of the Tombs is now exhausted,” he wrote in 1912. When he relinquished his concession, Lord Carnarvon, at Carter’s urging, snapped it up in June 1914.

Later that same month, the assassination of an Austro-Hungarian archduke plunged Europe and the Middle East into World War I, delaying a full-on search for Tutankhamun’s tomb until the fall of 1917, when improving news from the war allowed resumption of excavations. Over the next five years, Carter and a team of Egyptian laborers moved an astonishing 150,000 to 200,000 tons of rubble. The work was hard, dusty, and sweltering under the desert sun.

Those five years of pain produced little gain, and Carter’s benefactor grew disillusioned. Perhaps the valley was indeed picked over and played out. In June 1922 Lord Carnarvon summoned Carter to Highclere and announced he was giving up on the valley. Carter pleaded for one more season of digging, even offering to pay for it himself. Lord Carnarvon reluctantly agreed. When Carter arrived back in Luxor on October 28, 1922, the clock was ticking down. Seven days later, a chance discovery lifted his hopes—and soon upended his world.

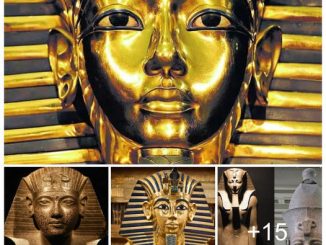

Egypt’s later pharaohs were believed to begin their journey to the afterlife in the Valley of the Kings, just west of the religious hub of Thebes. Most of the valley’s 64 known tombs were looted over the centuries. But in 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter made an astonishing discovery when he opened tomb KV 62: the treasures and mummified remains of the 18th dynasty pharaoh Tutankhamun.

On November 4, a member of Carter’s team whose name is lost to history stumbled upon a carved stone, the top of a buried stairway. In his pocket diary, Carter wrote just five words: “First steps of tomb found.”

The next day, the team uncovered 12 steps and descended to a doorway that had been plastered over and stamped with pharaonic seals. The seals were too indistinct to be read but were clearly unbroken. Convinced he’d discovered an intact royal tomb, Carter cabled Lord Carnarvon in England: “At last have made wonderful discovery in valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact … congratulations.”

News of the discovery spread quickly, and reporters raced to the valley to witness the opening of the tomb. Lord Carnarvon arrived on November 23, and by the 24th, Carter and his team had exposed the entire doorway and found seals that were more easily read. Several contained the long-sought-after name: “Nebkheperure,” the throne title of Tutankhamun.

Carter and his companions were elated, but a second discovery cast a shadow over the celebration: The doorway bore evidence of forced entry. Someone had been there before them.

The door was cut away, revealing not a treasure-filled tomb but a sloping passage filled with rubble. Two more days of digging brought them to the tomb, more than 20 feet underground. Another plastered doorway bore more seals naming Tutankhamun. Carter made a small hole in the masonry, held up a candle, and looked in. In what would become one of the most famous exchanges in the annals of archaeology, an impatient Lord Carnarvon asked, “Can you see anything?” to which Carter replied, “Yes. It’s wonderful.” (See the enduring power of King Tut as never before)

The objects he spied were indeed wondrous: golden beds, life-size guardian effigies, disassembled chariots, a richly decorated throne, all in a jumble. Carter wrote later, “At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold—everywhere the glint of gold.”

Tutankhamun’s tomb, Carter soon learned, included four rooms, now known as the antechamber, annex, treasury, and burial chamber. The tomb was unusually small for a pharaoh, but the rooms were packed with everything he would need to live like a king for all eternity—some 5,400 objects in all.

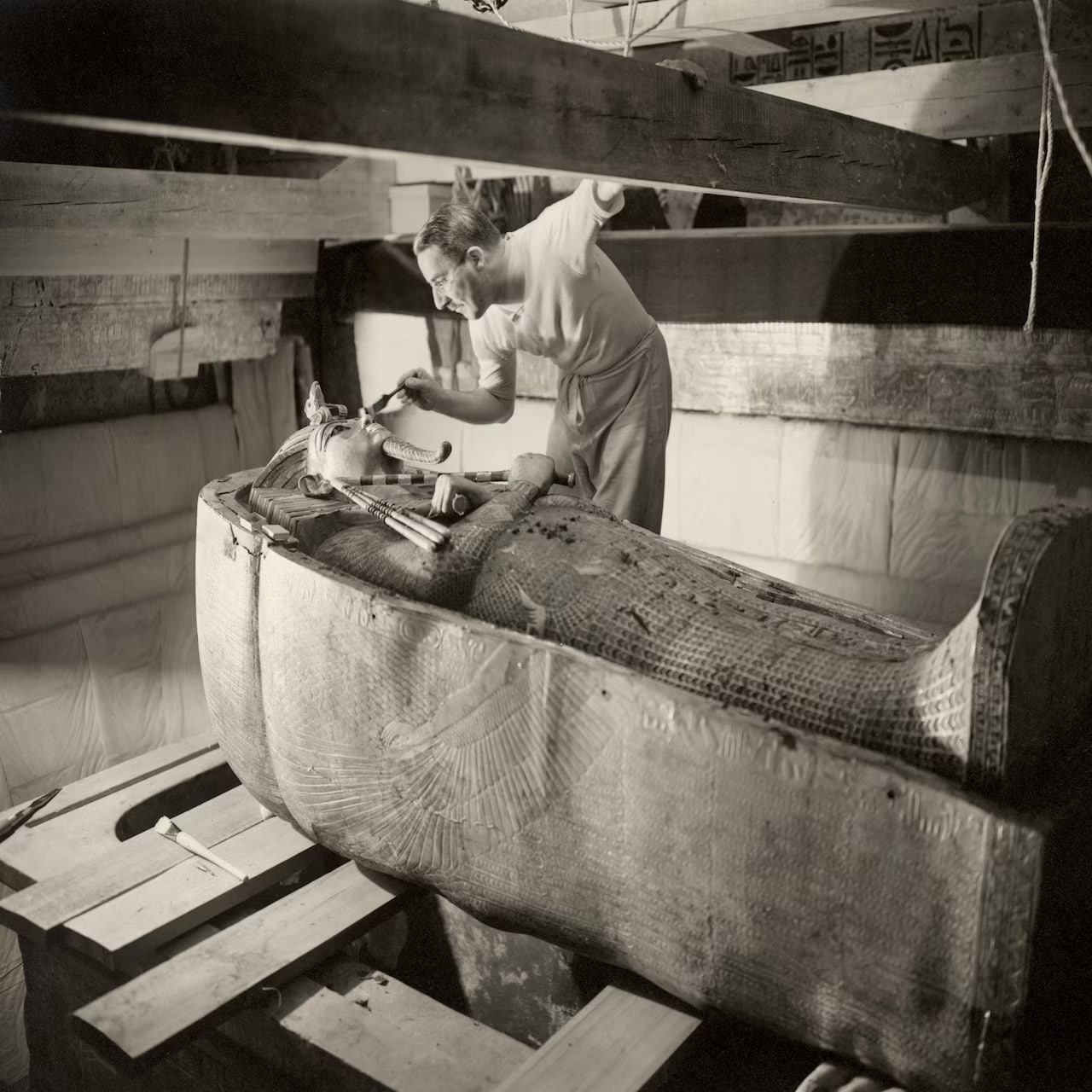

It was an archaeologist’s dream—and nightmare. Unpacking, cataloging, preserving, and moving the hoard of artifacts—many of which were damaged and fragile—would take a decade of painstaking work and involve an interdisciplinary team of specialists, including conservators, architects, linguists, historians, experts in botany and textiles, and others. The project signaled a new era of scientific rigor in Egyptology.