A gold treasure discovered in Andalusia in the 1950s caused a wave of speculation and debate: to whom did this sumptuous treasure belong? Where did that come from? And could it represent a piece of the puzzle in the Atlantis theory? Now, chemical analysis has revealed the origin of gold, providing some answers to the ancient mystery, while raising even more questions in the process.

Buried treasure

The El Carambolo treasure, consisting of 21 heavy blocks of gold, was discovered by construction workers on El Carambolo hill in Camas (Seville province, Andalusia, Spain) in September 1958. According to a recent study published in the Journal Journal of Archaeological Science, the gold was of local origin and was not imported by the Phoenicians as previously suspected.

Gold from El Carambolo treasure. (© José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Director of the Seville Archaeological Museum and one of the study’s authors, Ana Navarro told National Geographic: “Some people think that the Carambolo Treasure came from the East, from the Phoenicians. With this work, we know that the gold was taken from mines in Spain.”

A culture disappears

The discovery of the 2700-year-old treasure, consisting of 21 exquisite gold items packaged in a ceramic vase, awakened the interest of Tartessos. National Geographic reports that Tartessos was “a civilization that thrived in southern Spain between the ninth and sixth centuries BC. Ancient sources describe the Tartessians as a wealthy, advanced culture, ruled by a king. That wealth, and the fact that the Tartessians seemingly ‘disappeared’ from history some 2,500 years ago, have led to theories equating Tartessos with the legendary site of Atlantis.”

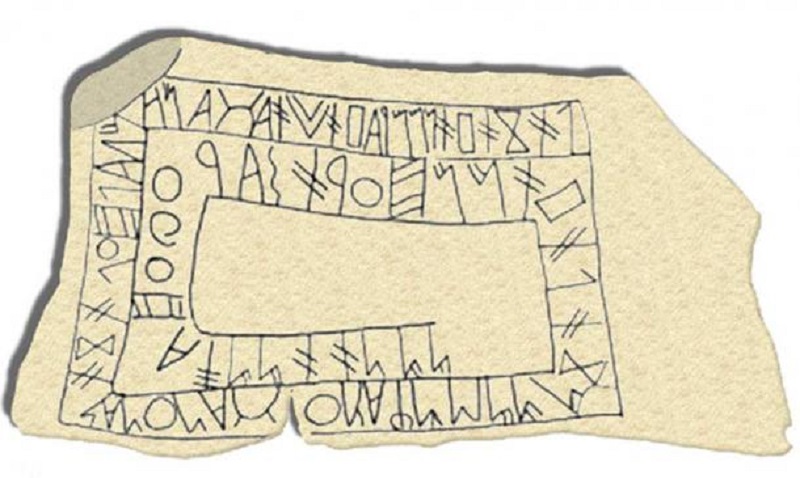

The Tartessian Fonte Velha inscription was found in Bensafrim, Lagos, Southern Portugal. (Public domain)

The Tartessians are believed to have developed a unique language and writing system that differed from their neighbors, and it is believed that they only received the cultural influence of the Egyptians and Phoenicians during the period. last.

Archaeologist Sebastian Celestino, while studying the ancient site in 2010, told the newspaper El Pais, “There were earthquakes and one of them caused a tsunami that flattened everything and appropriate to the era when Tartessian power was at its peak.”

The discovery of gold in the 1950s led to further excavations, and archaeologists discovered two separate settlements at El Carambolo; one reflects indigenous culture dating from the ninth to mid-eighth centuries BC, and another, later reflection, dates from the mid-eighth century; a trading center established around the time of the beginning of relations with the Phoenicians. Excavations at the newer site have revealed a Phoenician-inspired temple and a statue of the Phoenician goddess Astarte.

Tartessos Cultural District ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Celebrating the 50th anniversary of the discovery of El Carambolo treasure (in Spanish)

Gold on the hill

National Geographic writes that researchers “used chemical and isotopic analysis to examine small pieces of gold that broke off from one of the jewelry pieces. Analysis shows that the material may have come from the same mines associated with the monumental underground tombs at Valencina de la Concepcion, which date from the third millennium BC and are also located near Seville. The authors of the article assert that the jewelry of the Carambolo Treasure marks the end of a continuous goldsmithing tradition that began about 2,000 years ago with Valencina de la Concepcion.”

Gold processing is carried out in Valencina de la Conception. (Cazalla Montijano, Juan Carlos/ CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Gold pieces from the treasure. (© José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Treasures of both worlds

The question of who created the treasure is a mystery. Although researchers have determined that the gold was of local origin, it was produced in the Phoenician style and using their techniques. So the treasure was born from both worlds: Spanish gold and Phoenician fabrication.

“A Phoenician boy marries a local girl — to put it simply,” Alicia Perea told National Geographic. Perea is an archaeologist specializing in gold technology, working at the Center for Human and Social Sciences of the Spanish National Research Council.

The Carambolo sites were destroyed and abandoned after what could have been a large-scale disaster. Treasures found there date back to the 8th century BC, but it appears that the treasure was buried in the 6th century BC, left behind by someone fleeing a feud. unknown danger.

Necklace with pendant from hoarding. (Public domain)

The treasure includes 21 decorative gold pieces: a necklace, two bracelets, two breastplates decorated with bulls, and 16 plaques that together could form a necklace or crown.

Evidence of Atlantis?

The site’s possible inundation would add to the theory that its fate is linked to the story of Atlantis.

Cuban archaeologist Georgeos Diaz-Montexano, who has spent decades searching for the famously mysterious Atlantis, told The Telegraph: “There is more and more evidence that the story of Atlantis is not just fiction, a fable. proverb or myth but a true story as Plato always asserted.

However, researchers involved in the recent study and sites disapprove of such theories and call it “complete madness.”