Penn Museum casts new light on ancient Iraq

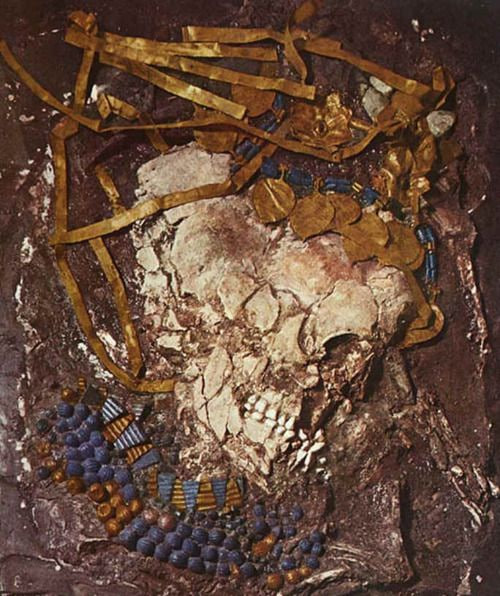

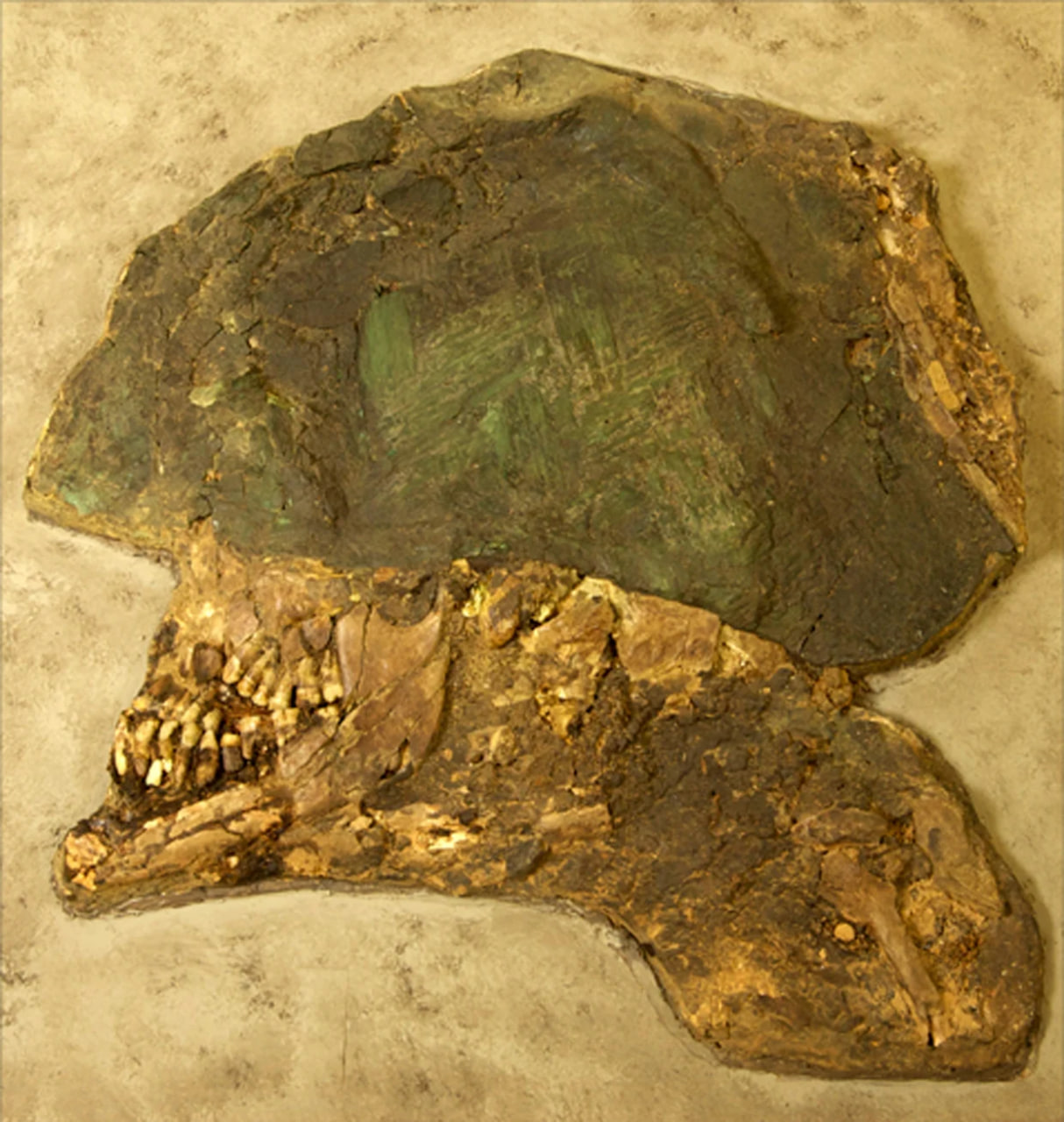

Ancient skull of a male guard from the “Great Death Pit,” a mass burial place of royal retainers flattened under the tombs of later burials. Profile of the head and helmet clearly shows teeth, and the outline of the chin and neck. Penn Museum

A flattened human head draped with gold and lapis lazuli jewelry lies in a glass case at the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, its teeth the only recognizable feature.

It’s all that remains of a female courtier to a Mesopotamian monarch who was buried around 4,500 years ago with all of his or her wealth, including the humans who attended the royal court.

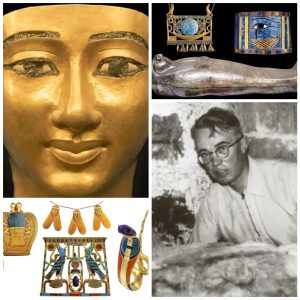

The attendant, together with several hundred others, was discovered in 16 royal tombs that generated international headlines in the 1920s when they were unearthed by British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley at Ur, near modern-day Nasiriyah in southern Iraq.

Now the remains, together with some 220 other objects from the site, are going on display at the Penn Museum for the first time in more than 10 years in a show that sheds new light on one of the great archaeological discoveries of the 20th century.

“Iraq’s Ancient Past: Rediscovering Ur’s Royal Cemetery”, a long-term exhibition opening on October 25, places the Ur treasures in the historic context of a region known as the “cradle of civilization”, and tells the story of their excavation between 1922 and 1934.

The objects have been on tour at art museums throughout the U.S. over the last decade, and have now returned to Penn — co-sponsor of the original 1922 expedition — which is emphasizing their historic and cultural significance rather than the aesthetic value highlighted by art museums, said co-curator Richard Zettler said.

The royal attendants found in the tombs were not poisoned, as suggested by Woolley, but killed by blows to the back of the head with a sharp object, a theory supported by recent CT scans by the University of Pennsylvania Hospital, Zettler said.

After death, bodies were dried out and treated with preservative so that they could be used in tableaux such as a banquet, demonstrating the monarch’s continued wealth and power even in death.

“These people were made to look like they were part of a funerary ritual,” Zettler said.

During burial, the remains were covered with such a weight of earth that skulls were crushed, explaining the flattened shape of the heads on display.