When Samhain approaches it doesn’t do to be wandering too near the underworld lair of the war goddess Morrigan.

Marked by whitethorn trees, the cave of Mór-Ríoghain, or the Great Queen, sits in east Connacht, within a couple of kilometres of the royal complex of Rathcroghan, one of the most significant but least appreciated archaeological landscapes on the island.

Resembling what the mountaineer Dermot Somers terms a “crack in the floor of time”, the narrow entrance to Uaimh na gCait, or Cave of the Cats, consists of a man-made souterrain and a natural limestone cavern.

Ogham inscribed on a lintel stone translates as “Frach, son of Medb”, referring to the queen associated with the area. Local myth has it that this was a gate to hell, marked by Morrigan, who harassed the cattle raiders of the Táin Bó Cuailgne after they set out from Rathcroghan to the Cooley Peninsula.

READ MORE

The plan for that campaign may have been hatched on top of this grassy mound, which was once an enclosure for a royal settlement and sacred burial place in the centre of Machaire Connacht.

One of four royal sites

Rathcroghan Mound was where the kings and queens of Connacht were inaugurated, in a ritual “mating” with the local Earth goddess. Irish medieval literature has many references to it as one of four major royal sites; the others are Tara, in Co Meath, Navan fort, in Co Armagh, and Knockaulin, in Co Kildare.

The eighth-century text known as the Táin Bó Fraích records how Medb and her husband, Ailill, had a house there built of pine, with “four pillars of copper” over their bed, which was “all adorned with bronze”.

Rathcroghan has survived as the nucleus of a complex of more than 60 monuments just northwest of the village of Tulsk, in Co Roscommon, where the community runs a visitor centre known as Cruachán Aí.

The centre allows visitors to travel in time from the Mesolithic – 6,000 BC to 4,500 BC – to the Iron Age. Much of the tour trail has been informed by geophysical surveys by NUIG’s school of geography and archaeology, in association with earth- and ocean-science colleagues.

As Joe Fenwick, an NUIG field officer, says, geophysical surveying is uninvasive but very good at interpreting the physical or chemical properties of the soil. “I feel very differently now about Rathcroghan, knowing what we know now, than when I came here first,” he says as we walk to the mound. “This was a very pagan landscape which has been preserved through Christian times, largely due to agricultural practices. You have a corduroy-like pattern of cultivation in surrounding fields, but the mound itself was never touched.”

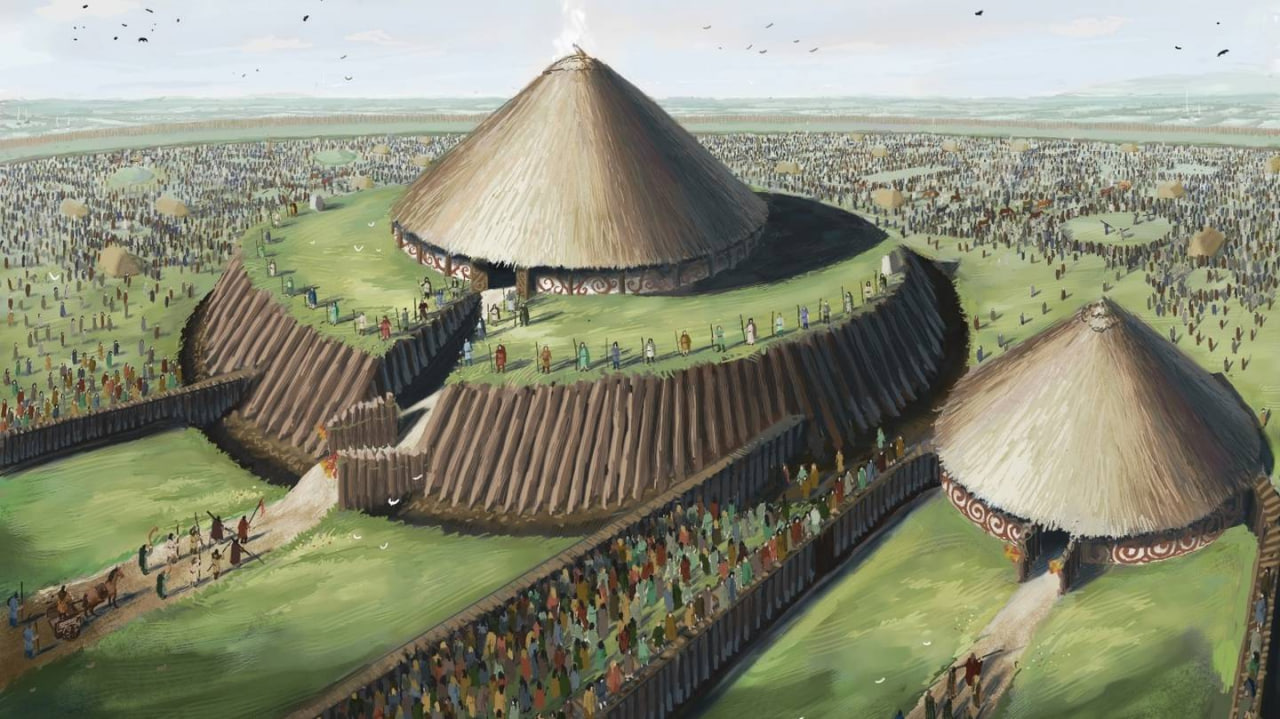

About the same size as Newgrange, Rathcroghan was once approached by an east-facing avenue. There are the remains of two concentric stone walls within a perimeter retained by a timber palisade; there is also evidence of timber structures on its summit. “There is no definitive proof of roofing, but the Romans were building the Pantheon at the time, so I am sure that these inhabitants could roof an Iron Age structure, even with wood,” Fenwick says.

It is surrounded by 19 enclosures, 28 burial mounds, pillar stones and other earthworks. Among these are a raised ring fort known as an Ráth Mór, a ring-barrow burial mound known as an Ráth Beag, and a 170m ring fort known as Ráth na dTarbh, where the white-horned bull and the brown bull of Cooley are said to have met at the end of the Táin Bó Cuailgne.

First contemporary study

Rathcroghan’s first contemporary study was published by Prof John Waddell in 1983. His fellow archaeologist Prof Michael Herity also published a series of papers on aspects of the area’s archaeology.

The imaging project was initiated in 1994 with Heritage Council funding; much of this work is documented by Waddell, Fenwick and Kevin Barton in a 2009 book entitled Rathcroghan: Archaeological and Geophysical Survey in a Ritual Landscape.

A new phase of geophysical surveying over the past three years is still ongoing, Fenwick says. Ground-penetrating radar and magnetic gradiometry can pick up very different underlying features across the same area, he says. An example is the contrasting geophysical images of Rathcroghan’s “northern enclosure”, showing the subsurface remains of an Iron Age circular wooden temple or shrine, perhaps dating to the centuries immediately before the birth of Christ.

“In this case the radar actually picked up traces of two concentric slot trenches, between half a metre and a metre below the surface, which, remarkably, were not detected in the gradiometer survey,” Fenwick says. “It appears, therefore, that this temple or shrine was built and rebuilt a number of times.”

He has also worked with Dr Paul Naessens of Western Aerial Surveys on a computer-generated three-dimensional map of the mound and its surroundings. Two new information panels at the location include an artist’s impression, by JG O’Donoghue, of what Rathcroghan might have looked like.

With Dublin growing at an inexorable rate, the richly historic landscape of Rathcroghan is expected to survive well beyond that of Tara.

Rathcroghan Mound and other major monuments are in State ownership, but others are on private land, so seek the landowner’s permission; rathcroghan.ie