Gazing at the beautiful red garnets glinting in gold at the Corinium Museum’s Anglo-Saxon exhibit, I could imagine the lustre of the dragon’s hoard in ‘Beowulf’, brought to life through archaeology. My love of early medieval artefacts and literature grew through studying Fine Art, English Literature and Medieval History A-Levels, yet this exhibit has inspired me to consider Old English literature with a new light on archaeology, landscape and material culture.

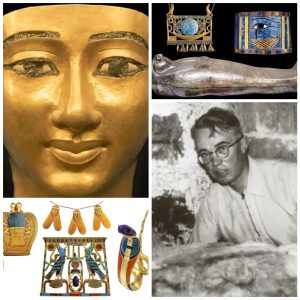

The artefact that most inspired me during my visit was the gold disc pendant set with garnets, dating from the seventh century, which was found while excavating grave 95/1 at Butler’s Field, Lechlade in 1985.

The Anglo-Saxon cemetery at Butler’s Field held the buried remains of 248 men, women and children who lived in a modest settlement compared with the wealth of their grave goods. Significantly, the site was occupied by both pagan and Christian burials from the late fifth to early eighth centuries, establishing a culture of spiritual ambivalence during the conversion to Christianity in England.

As the conversion began in the late sixth century, the seventh century pendant was created with Christian iconography: its cruciform design, and the red garnet, or carbuncle, gemstones are referred to in the biblical Book of Revelation and in early medieval literature. The literary form of the lapidary, an encyclopaedia of jewels, compiled the properties, symbolism and medical qualities of precious and semi-precious stones 1, yet the basic meaning of jewels was mainly limited to the educated classes. However, the carbuncle was ‘one of the best-known gems’ 2, and it was featured in an Old English lapidary dated to the mid-eleventh-century from the Cotton Tiberius A. iii manuscript at the British Library. In this lapidary, the carbuncle is described ‘like a burning coal’ 3, alluding to medieval literature where the stone could magically illuminate dark spaces, and the dark red hue of the stone visually confirms this description. Yet archaeological evidence from other seventh century Anglo-Saxon artefacts with red garnets, like the Sutton Hoo helmet, transforms the fictional quality of the carbuncle as an illuminator into a more tangible reality. The Sutton Hoo helmet – at the British Museum – has a line of red garnets embedded in the eyebrows, and on one side each garnet is backed with a gold foil to reflect the light and glow red, ‘like a bike reflector’ 4, to illuminate the dark.

Elemental themes of fire, darkness and light are present in Old English literature, such as the poem ‘Beowulf’ to create a metaphor for the moral ambiguities of heroism and monstrosity. The warrior Beowulf fights the monsters Grendel, Grendel’s Mother and a dragon in a midnight mead-hall, underwater in a haunted lake and in an underground cavern near the dragon’s hoard. These subterranean, isolated landscapes are home to the non-conformist opponents which Beowulf fights, yet in defeating them, could his own humanity be questioned? The defeat of the inhuman could only be enacted by some being of greater inhuman strength, yet perhaps this illustrates the main struggle in the poem as survival. Anglo-Saxon society was militaristic, reliant on ties of loyalty and kinship, which is evidenced through the weaponry grave goods at Butler’s Field: armour, arrows and shields.

Old English riddles, included in the Exeter Book manuscript, construct metaphors that blur the meaning of popular objects from Anglo-Saxon society. Echoing the elemental imagery of the pendant, in Riddle 30a, the Timber-Cross, the Christian cross of crucifixion is animated into a living, tormented thing:

‘I am concerned with fire, at play with the wind, spun about with glory, made one with the firmament, eager for the outward way, afflicted by burning, blossoming in the coppice, a burning ember.’5

Although Riddle 48 expresses the sacramental paten or chalice, which are vessels used during the Eucharist in Christian worship, references to ‘a circlet…the secret of the red gold and its occult utterance’ remind me of the Anglo-Saxon pendant. The circular composition of the pendant itself and as a necklace echo the vessels, while the red garnets within it echo the ‘red gold’ that alludes to the blood of Christ, solidifying the pendant as an expression of Christian faith for the wearer.

Yet who wore this pendant? A thirty-five to forty-year-old Anglo-Saxon woman wore it regularly as a necklace. Archaeologically, this can be seen from signs of wear on the pendant and the position of the pendant on her buried body. The high-quality metalwork of the pendant itself and evidence of its Christian iconography perhaps illustrates her as a religious authority in her local community 7.

Necklaces described in the Old English poem ‘Beowulf’ belong to the tradition of material exchange in Anglo-Saxon culture. Through loyalty, looting, fighting and mourning, material culture is omnipresent in fights against monsters, on funeral pyres, journeys across the sea, and gifting heroes with wondrous jewels and armour.

The poet writing ‘Beowulf’ is aware of the artistic composition of metalwork, with armour described as ‘the brightly forged / work of goldsmiths’8 , as well as the literary composition of the poem itself. References to necklaces in the poem reveal their amuletic as well as spiritual nature, as the Queen Wealhtheow enthuses to Beowulf after he slays the monster Grendel, ‘Take delight in this torque, dear Beowulf, / wear it for luck… I wish you a lifetime’s luck and blessings / to enjoy this treasure.9’ The warrior Beowulf gifts this torque to his lord, King Hygelac, who will die wearing it, as time shifts mean that objects move through different hands throughout time within the poem. The integration of the spiritual and secular is also present in this specific necklace, as it is expressed as ‘the most resplendent / torque of gold I have ever heard tell of / anywhere on earth or under heaven.10′

Through archaeological and literary evidence, the pendant was a spiritual symbol signalling the woman’s public identity within the secular context of her local community, yet it also existed as a personal belonging revealing her private need for the magical protection of an amulet.

Once again, this signals the integration of pagan and Christian belief in the seventh century, while ‘Beowulf’ was believed to have been composed between the seventh and tenth centuries with Christian hindsight on the pagan traditions it describes. Set in Scandinavia, the poem describes Beowulf’s torque as ‘Brosings’ neck-chain’ 11, the goddess Freyja’s necklace, the Brisingamen, from Norse mythology. Etymologically, the Old Norse brísingr meant ‘fire’ or ‘blaze’, which links back to the pendant’s burning description in the Old English lapidary. In the Corinium Museum’s Anglo-Saxon exhibit, there is a plaited Anglo-Norse ring, the Tunley torc, which visually matches frequent descriptions of coiled jewellery in ‘Beowulf’.

Within ‘Beowulf’, female figures like Queen Wealhtheow hold the political, diplomatic power of material exchange during feasts, where she presents Beowulf with his torque, yet the queen wears jewellery that signals her own high status. The poet describes her as ‘Adorned in gold…queenly and dignified, decked out in rings, / offering the goblet to all ranks… regal and arrayed with gold’. With a particular focus on gold, this suggests that the pendants found in the female graves at Butler’s Field indicate their owner’s high social status.

Artefacts from the grave of a twenty-five to thirty-year old woman, who lived in the sixth century, reveal her powerful status: a bone comb, hair decorations, a blue glass and bone beaded necklace, a beaver’s tooth pendant, a large bronze decorated square-headed brooch, two bronze decorated saucer brooches and two silver spiral rings. This was the grave of ‘Mrs Getty’, whose burial has been reconstructed in a display at the Corinium Museum. Her beaver’s tooth pendant may have been an amulet, continuing the amuletic tradition of jewellery from the sixth century to the seventh century owner of the gold pendant.

When Beowulf is buried at the end of the poem, the importance of the material culture in his grave is sadly dismissed by the poet:

‘And they buried torques in the barrow, and jewels

and a trove of such things as trespassing men

had once dared to drag from the hoard.

They let the ground keep that ancestral treasure,

gold under gravel, gone to earth,

as useless to men now as it ever was.’ 12

However, examining early medieval archaeology or literature independently would not develop the rich knowledge we have of Anglo-Saxon society today. Using an interdisciplinary approach, through archaeology and material culture, we can contextualise the themes in Old English texts more clearly. The elemental, devotional and secular nature of Anglo-Saxon jewellery can inform us of past lives, both real and fictional.

Come and visit all these beautiful Anglo-Saxon wonders! The Corinium Museum’s exhibit is infinitely inspirational with displays of Anglo-Saxon jewellery among other artefacts from early medieval culture.

Written by Annabel Brodersen