In the Campania region of Italy near present-day Naples, there was once a prosperous Roman city – Pompeii. A thriving commercial center, the city’s residents were a mix of elites and slaves. Regardless of their social class, they lead fascinating and sometimes scandalous lives.

Pompeii’s residents left behind a number of detailed written accounts about everything from trade and population to politics and daily life. But however valuable these documents are, they are overshadowed by the unique state of preservation of the city, which was overcome by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, located 5 miles from town.

Although many people first think of plaster statues of victims who died in the eruption when they think of Pompeii, there’s much more to this city than that. The fateful eruption that preserved the city in all its glory may have been disastrous for most of its inhabitants, but it left behind an exceptional and complete record of life in a bustling Roman city at the height of the Roman Empire and considered by many to be the richest archaeological site in the world.

Pompeii’s earliest settlement

While the ruins that people think of today are from the Roman period, Pompeii dates back to the 8th century BC. The area was settled by a group from central Italy called the Oscans, who considered the location ideal due to its favorable climate and fertile volcanic soil.

While grapes and olives are bountiful thanks to the rich soil. Little did the Oscans know that this was due to the activity of the beautiful and harmless mountain that formed the innocent backdrop of their idyllic settlement.

Beautiful Mount Vesuvius, backdrop of Pompeii. ( dudlajzov / Adobe Stock)

The population increased as the Greeks moved into Campania and for a time were joined by the Etruscans.

After the defeat of the Etruscans in 474 BC, they retreated from the area and were replaced by the Samnites who lived in the local mountains but expanded further and moved to cities such as Pompeii. From 343 to 290 BC, a series of battles between the Samnites marked the beginning of Roman influence over the city.

Roman Pompeii and the Siege of Sulla

With rich resources and favorable location, Pompeii quickly became Rome’s favorite city. The city grew and developed actively thanks to the empire investing in large construction projects in the city in the 2nd century BC.

But the city’s Samnite and Oscan origins meant that it was always separate from other cities and it considered itself somewhat independent from Roman rule. In 89 BC, it was besieged by a Roman general named Sulla, who aimed to strengthen the empire’s control over Pompeii. The siege was a success for Sulla and those who showed any resistance to Roman rule were driven from the city while the remaining residents fought and were later granted Roman citizenship.

Pompeii was now officially a Roman colony, and it was given the Latin name Colonia Coernelia Veneria Pompeianorum after the prestigious house of Cornelia and the goddess Venus. Just like the city itself, many of its more aristocratic residents used Latinized versions of their names as a sign of their integration into Roman society.

Pompeii became an important part of the Roman trade route with many goods arriving by sea, passing through the city on their way to Rome. Although Sulla’s veterans initially controlled politics in Pompeii, they clearly gained Roman respect as some names of Oscan origin began to reappear in political positions. local authority several decades after the siege.

After the siege, Pompeii entered a second era of prosperity and a new amphitheater seating 5000 people was built along with an odeon large enough for 1500 people. As was the case with most Roman cities, Pompeii was surrounded by a wall, which was intended to be easier to defend in the event of a siege.

A series of gates serve to separate pedestrians and traffic such as product delivery vehicles. Inside the walls, the city is laid out in traditional Roman style in systematic rows on a grid system, except for the southwest corner which has an unusually chaotic layout. There is evidence that some streets are operated on a one-way system.

People and tourists visit Roman Pompeii

In the years before its destruction, Pompeii was a prosperous city with a large population. Up to 12,000 people lived in the city itself with up to a third of them being slaves. The number of people living in villas and farmland around the city doubled.

Although Pompeii is located inland today, at the time of the eruption it was a coastal city and very popular with the well-off. This means there are several large villas with impressive sea views. Emperor Nero had a villa near or in Pompeii and his wife Poppaea Sabina was a native of the city.

Naples coast (Pompeii) with Mount Vesuvius at sunset. (JFL Photography/Adobe Stock)

Two of the most famous visitors to Pompeii were Gaius Plinicus Secunus and Gaius Caecilius – better known as Pliny the Elder and Pliny the Younger. They were all notable figures in ancient Rome. Pliny the Elder was a natural philosopher, author, military commander, and close friend of the emperor Vespasian. His grandson Pliny the Younger was an author, lawyer and judge.

Pliny the Elder lost his life trying to rescue people and families from the eruption. Winds carrying poisonous gases meant his ship was unable to leave port and he is said to have been overwhelmed by the smoke or suffered a heart attack leading to confusion and panic.

The remaining 247 letters written by Pliny the Younger are of great value to historians. Many of his letters were written to important political figures and some were even sent to reigning emperors. He also provided evidence of seismic activity leading up to the eruption, stating that the Romans were familiar with earthquakes and tremors in the area and did not consider them worrying or alarming because they occurred so often. frequent.

He also wrote two letters about the eruption, 25 years after the event, which were sent to Tacitus in response to a request for information about the death of Pliny the Elder. His meticulous description of the events was so detailed that the type of eruption that destroyed Pompeii is still known as the ‘Plinian eruption’.

Left – Plinian eruption: 1: ash plume, 2: magma conduit, 3: volcanic ash fall, 4: lava and ash layers, 5: stratum, 6: magma chamber. Right – Pompeii and other cities affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The black cloud symbolizes the general distribution of ash and coal. The modern coastline is shown. (Left, CC BY-SA 4.0 / Right, CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Life in the city of Pompeii

Pompeii was an important part of the Roman trade network. Diverse goods pass through the city. Olives and olive byproducts, wine, wool, a fish sauce called garum, salt, walnuts, figs, almonds, cherries, apricots, onions, cabbage, and rice noodles are exported. They imported luxury goods such as foreign fruits, spices, silk, sandalwood, wild animals to fight in the arena, and slaves.

The people of Pompeii had a diverse diet. Along with the items they traded, they ate beef, pork, birds, fish, oysters, crustaceans, snails, lemons, figs, honey, lettuce, artichokes, beans and peas. Wealthier citizens would have greater access to these, as well as delicacies like honey-roasted rats. Access to such a diverse range of foods was one reason the area was so attractive and attracted so many wealthy members of Roman society.

There are thousands of buildings in Pompeii, representing a cross-section of Roman society. There were large, almost grotesque mansions with a luxurious appearance and housing for the poorer members of society. Stores and markets reveal how people buy. Pubs, theaters and brothels show the variety of ways people spent their leisure time.

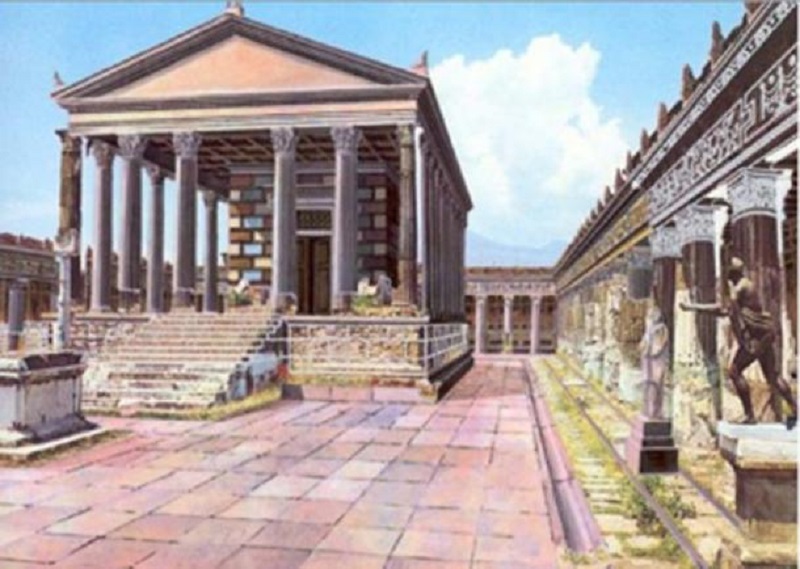

Pagodas and hundreds of shrines worshiping gods and ancestors create a picture of the religious life of the residents. There are schools, public toilets, bathhouses, flower nurseries, exercise fields, churches and water towers. All the buildings that make up a typical Roman city – and more. Everything points to a city experiencing its golden age, with countless amenities available to those who live and visit it.

Illustration recreating what the Temple of Apollo in Pompeii looked like before the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. (DuendeThumb / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Many of Pompeii’s lavish villas were built in a style that reflects the previous Greek influence on the area, and many of the houses with private gardens often have areas dedicated to winemaking.

But with a third of Pompeii’s inhabitants held as slaves, living conditions were much less luxurious and the slave quarters saw people living in prison-like conditions, in extremely cramped rooms cramped. Lower-class prostitutes served their customers from buildings that were little more than curtained rooms.

The mountain and the destruction of Pompeii

Vesuvius is the only volcano to erupt on the European continent in the last hundred years and is considered by many to be the most dangerous volcano in the world because three million people now live near it. Its eruptions tend to be violent and explosive, adding to the dangers and risks of living in its shadow.

There were at least 11 major eruptions before the settlement of Pompeii, but the volcano would lie dormant – sometimes for centuries – between them, and the Oscans were not aware of the volcano’s power when they settled in Pompeii. However, there are mentions of earlier eruptions in Greek mythology. The demigod Hercules is said to have fought fiercely against mighty giants in the fiery landscape around Vesuvius, and the city of Herculaneum was eventually destroyed in the same eruption for which Pompeii was named him, to pay homage to the legends.

The eruption that destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum occurred in 79 AD. On the morning of August 24, thousand-year-old lava erupted from the volcano with a resounding explosion. Residents may have seen an impressive display of fire and smoke but were not immediately alarmed.

Artist’s impression of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii. (Dcoetzee / Public Domain)

Only after the second and larger explosion hours later did the catastrophic nature of the situation become clear. Scientists have calculated that the power of the explosion was 100,000 times stronger than the nuclear bomb that wiped out Hiroshima. As the inhabitants of Pompeii began to flee for shelter, ash began to fly down on them, covering everything and quickly growing several centimeters thick.

As the days passed, the ash continued to fall. The city was buried in meters of rubble and the roofs of buildings began to collapse under its weight. Those unable to escape sought shelter anywhere they thought they could be protected – near walls or huddled with loved ones under the stairs.

Those unable to escape sought shelter wherever they could. (marneejill / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

The final fate of Pompeii and those who could not escape was decided at around 11pm when the ash cloud collapsed and the city was hit by a wave of lava. The streets were filled with toxic gas that could suffocate anyone unlucky enough to survive, and the intense heat caused bodies to later roast to death.

When the last ash fell, the city was completely covered. Meters of debris cover a city that was once an integral part of the Roman Empire and a desirable location for wealthy and influential members of the Roman elite. In just a few hours, Pompeii was buried and it was largely forgotten until in 1755 A.D. local legends of a preserved ancient city were proven true during the construction of a new channel.

When the city was excavated in the 19th century, the inhabitants were revealed after 1700 years of being buried in the city. Surprisingly, archaeologists realized the skeletal remains were surrounded by air pockets. As the bodies decomposed, the outline of their final resting place remained imprinted in the compressed ash that surrounded them.

Victims of the volcanic eruption in Pompeii are still covered in ash. (themadpenguin / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

As plaster of Paris was carefully poured into the voids, the bodies were brought back to life in astonishing detail. As well as their final poses, the clothes and faces of the inhabitants of Pompeii have been preserved. It shows people clinging to loved ones, curling up and covering their mouths to try to escape toxic fumes, or holding on to precious objects so they don’t get lost or stolen.

Despite the stark difference in fortune observed in the rest of the city, those who died there revealed themselves on another level – the rich and the poor were no different. The people of Pompeii all died in the same tragic way, no matter what part of the city they called.