When we think of wind power as a source of energy, we might think of huge, ugly turbines blighting the landscape. But one village in Iran reveals how our ancestors built turbines using wood and clay, not steel and concrete; with such smarts, they are still being used today—some thousand years on.

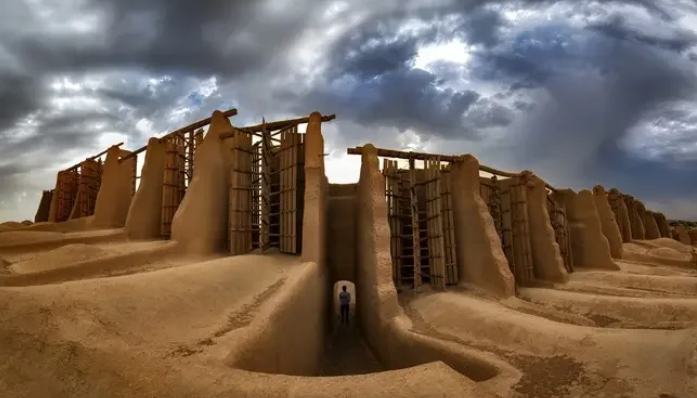

The name of the tiny town in the country’s northeast means “storm’s sting,” due to the ferocity of the winds that blow from the north year-round. Situated on a windswept plain approximately 25 miles (40 kilometers) from the Afghan border, Nashtifan is famous for its ancient windmills, the oldest in the world.

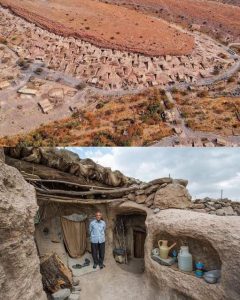

Blending into the semi-desert landscape, constructed high on a hill, an army of 40 windmills stand up to 65 feet (approx. 20 meters) high and serve two purposes: to act as a buffer, protecting the village from the raging air currents, and to grind grain into flour. Locals call the technique of using wind to power milling machinery “asbad.” In a stroke of genius, Iranian architects positioned and designed the windmills in such a way as to “catch” the air in openings, causing the blades to spin, which in turn powers a vertical shaft that turns a millstone, grinding the grain.

The 1,000-year-old windmills in Nashtifan in Iran, near the border with Afghanistan. (V4ID Afsahi/Shutterstock)

Dark clouds loom over the windmills of Nashtifan, Iran. (Hadidehghanpour/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Every year from late May to late September, fantastically strong gusts pick up even more. According to UNESCO, it is known as the “120-day wind or black wind,” and speeds sometimes reach 60 miles (100 kilometers) per hour. Such persistent conditions, combined with a lack of water in the area, prompted the engineers of the time to come up with the idea of optimizing its power. Everything was constructed using natural materials. In addition to wood, clay, and straw they used locally-grown palm leaves for the blades, which were woven tightly together and attached to the central shaft.

One man has dedicated his life to taking care of the unique structures. Custodian Ali Mohammad Etebari has spent long years carrying out daily checks and maintenance. Speaking in an interview with the International Wood Culture Society in 2017, Etebari said: “We put the wheat, we get the powder … we make nan bread, we eat it, we enjoy it.

“I was a driver and as well I’ve been looking after this for the last 28 years.”

The windmills in Nashtifan are still operational after about 1,000 years. (V4ID Afsahi/Shutterstock)

The windmills in Nashtifan provide power for grinding grain into flour. (V4ID Afsahi/Shutterstock)

The elderly man explained that, historically, several members of the same family would look after one single mill; but now, it’s just himself, acting as caretaker for all of them. The near-perfect preservation of the windmills is down to the arid climate.

“Here, there is no humidity,” he said. “It’s very dry, so they last a long time.”

The wheat produced by this truly artisan process is “so much different,” said Etebari. “It’s very tasty, very healthy, and it’s good for the stomach. This wheat is complete; the wheat you get on the outside, it’s incomplete.”

Besides providing locals with wind power for grinding grain into flour, the windmills also buffer the strong winds in northeastern Iran. (V4ID Afsahi/Shutterstock)

Going on to explain the lack of wealth in his town, Etebari marveled at the ingenuity of the windmills.

“They are working without any electricity, without any diesel, benzin [fuel], or any other things. Just by the wind—and for the wind, we don’t pay anything.”

According to his wisdom, it was important that the tree trunks used for the vertical shaft and other parts be left with the bark intact, otherwise, the wood would crack.

“I’m the one who looks after it,” Etebari said with some pride. “If I don’t look after it, the youngsters will come and spoil it, and break things. The kids come and disturb it, throwing stones.”

Grains are ground into flour in windmills in Nashtifan, Iran. (V4ID Afsahi/Shutterstock)

Wooden turbines harness the power of the wind while also buffering the strong winds for the inhabitants of Nashtifan, Iran. (V4ID Afsahi/Shutterstock)

The Nashtifan windmills in Iran (Hamed Yeganeh/Shutterstock)

Etebari’s last remark is poignant. “I’m the only one who is looking after this,” he said, climbing up to inspect the nearest windmill, stooped in his posture.

Knowing how the old man put his heart and soul into maintaining one of Nashtifan’s vital food sources, and the incredible nature of this ancient engineering feat, some might be heartened to know several official bodies, including the Iran Heritage Foundation, have undertaken restoration efforts at the site. Considered one of the first examples of wind power technology on the planet, the Nashtifan windmills are also under consideration for nomination as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Historically known as Persia, Iran’s use of windmills is believed to date back around 5,000 years, its design later spreading across the world.