The three great pyramids of Egypt have stood tall for some 4,500 years. By the late 1800s erosion on the Giza plateau raised fears among scholars that the grand structures were threatened. Illicit digging in the area was the suspected cause, and a team of scholars knew that a solution was necessary.

In 1902 a group of them met at a Cairo hotel to come up with a plan. In attendance were German Ludwig Borchardt, who would discover the Nefertiti bust in 1912; Italian Ernesto Schiaparelli, who in 1904 would find the tomb of Nefertari, queen of Ramses II; and George Reisner—known as the “American Flinders Petrie” because his cautious methods were compared to that of the celebrated British Egyptologist. The group decided to divide up the plateau among them so that teams could organize and conduct their own excavations.

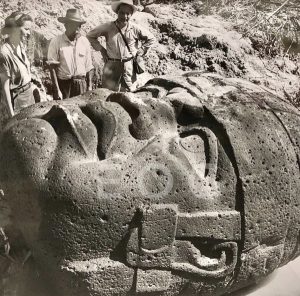

Standing on the veranda, they drew lots from a hat. Borchardt won the Pyramid of Khafre, and Schiaparelli part of the cemetery to the north. Reisner picked the funerary complex of the pharaoh Menkaure, a section that would yield some of the most iconic artworks from the Old Kingdom.

Buried Treasure

Menkaure, the sixth ruler of Egypt’s 4th dynasty, was buried in the smallest of the three great pyramids. His father Khafre and his grandfather Khufu (Cheops in Greek) rested in the other two. Built between 2550 and 2490 B.C., the Giza Pyramids stand as an eternal symbol of Egypt.

This fate, however, was not shared by Menkaure’s mortuary temples, which Reisner believed to be located on the pyramid’s eastern side. These temples would be the center of a cult to worship the dead pharaoh. Evidence suggests that Menkaure’s temples operated for nearly three centuries after the pharaoh’s death. After his cult declined, so did the temples, and they disappeared beneath the sands.

The Pyramid of Menkaure had long ago been plundered by robbers in the ancient era. Centuries later, other Menkaure artifacts would be lost to time as well. In the 1830s British soldier Richard Vyse entered the structure and found the empty sarcophagus of the king, which he shipped off to London. The ship carrying it was wrecked, and Menkaure’s sarcophagus ended up on the seabed. Reisner hoped that locating the lost temples would yield artifacts that would compensate for the theft and loss of so many objects from the pyramid, and shed much needed light on this period of the Old Kingdom.

In 1906 Reisner was ready to begin searching his alloted share of the Giza complex. The head of an expedition organized by Harvard University, Reisner would patiently and methodically excavate the site. His prudence paid off. In December he uncovered the “Upper Temple.” In June 1908 he found another major structure, known as the “Valley Temple,” crudely constructed due to the king’s sudden, unexpected death.

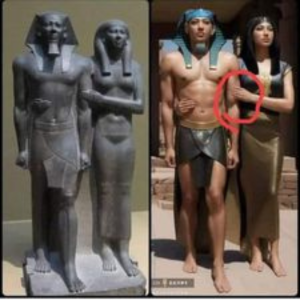

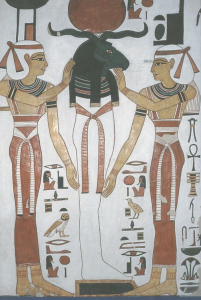

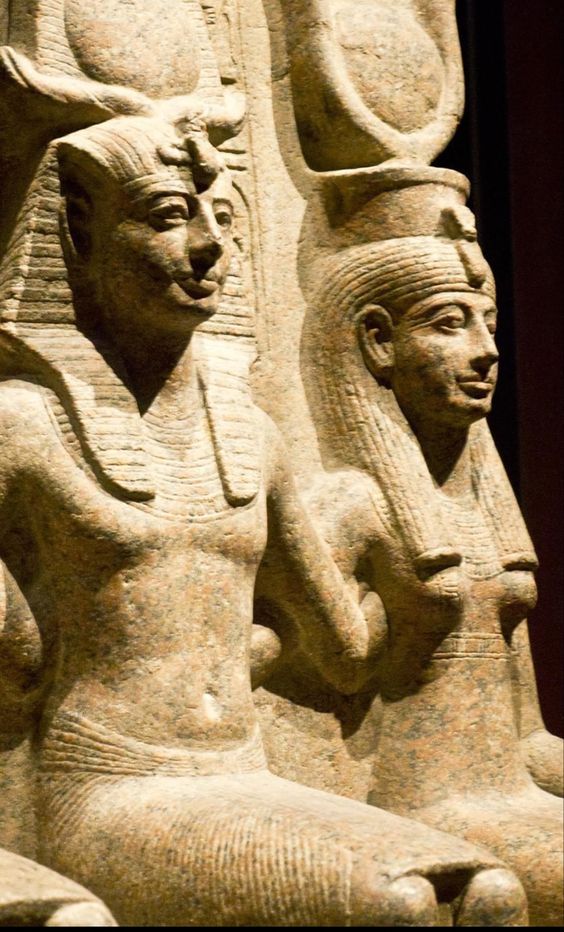

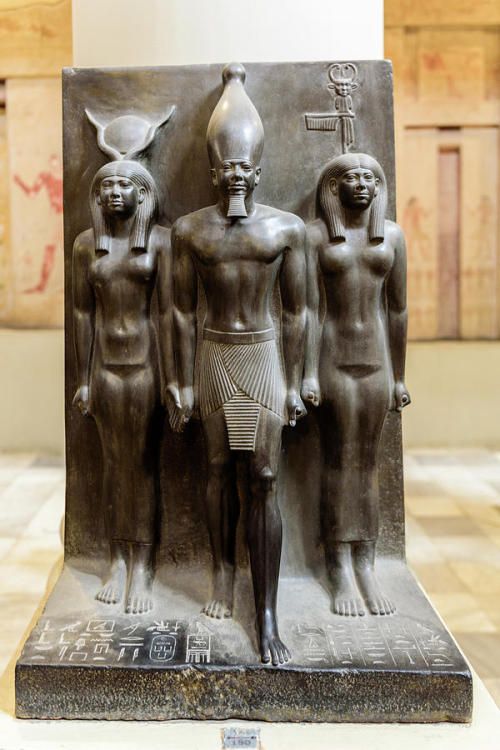

As excavation continued, Reisner found a cache of remarkable artworks celebrating Menkaure in the Valley Temple. The most notable were four intact triads (groups of three figures) carved from graywacke, a type of sandstone. Preserved in near-perfect condition, the four pieces depict, in varying configurations: Menkaure wearing the tall crown, or hedjet, of Upper Egypt; the goddess Hathor, identified by her characteristic horned headdress and solar disk; and a third figure personifying regional deities from the provinces of Egypt.