The tale behind the whale that Adrián Villas Rojas left at The End of the World

How did this artist make his name with a beautiful, but incredibly obscure, work that’s almost impossible to experience first-hand?

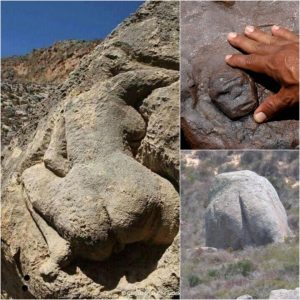

In the spring of 2009 Adrián Villar Rojas and his team began to collect clay from a public quarry on the outskirts of Ushuaia, a town on the farthest most southerly tip of Argentina. “To prepare the clay, the team resorted to hand sieving to remove the pebbles,” explains our new book on Villar Rojas. “They also softened hard lumps by wrapping them in nylon and squashing them under their feet.”

They had a lot to get through. Villar Rojas had been invited to take part in the second End of the World Biennial, held in this remote tip part of Latin America. However, rather than create something in a gallery space within Ushuaia’s city limits, Villar Rojas chose to accentuate the geographical extremism a little further, by creating a strange, temporary work, outside Ushuaia, in the nearby Yatana Forest. And it wasn’t any old work; he had decided to make a whale out of raw, unfired clay.

“The first time I went to Yatana, I was immediately fascinated by the idea of people wandering around a forest, nowhere near the biennial site, getting lost, seeing no signage or directions, then finding nothing, or eventually finding a whale made of earth, with its skin sprouting fungus and plants,” the Argentinian artist tells the writer and curator in our new book.

“I wanted the people who found our whale, emancipated from the expectations of trying to find an artefact that was part of the biennial apparatus, to have the feelings and questions that those who discovered the humpback in Brazil must have had: How did this get here? Who did this? Is this some end-of-the-world scenario? What back in 2009 could be read as a sci-fi image or a fantasy, has now become a mundane transcription of the climate crisis: a bloated, decomposing cetacean beached in a forest is no longer surreal, it is a political and environmental reality.”

Today the piece is an early signature work by an artist who the New York Times describes as having “a sci-fi writer’s imagination and an ecologist’s anxieties.” And the unfired clay model certainly fired up the imaginations of those who were lucky enough to see it before it disintegrated.

“The twenty-seven-by-three-by-four-metre sculpture, made of an inner wooden structure and covered in raw clay, began to crack immediately upon completion” writes museum director and author Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev in our book. “Clay comes from the erosion of mountains by rain and rivers, and in a notebook from 2008, where he conceived the piece, Villar Rojas noted, ‘It would be good that the same weather degrades everything rivers of clay)’. He has stated elsewhere, ‘It was there that I realized I could build my own ruins’.”

In some ways, the sculpture is not hard to interpret. The scale and size of the piece is impressive; the title is shocking; there are obvious environmental overtones; and perhaps an element of personal, ecological protest. In retrospect, its importance is clear: with this work, Villar Rojas went from being a promising young Argentinian artist to a world-wide art star.

Yet the requirements that this artwork placed on its viewers – to get to what is often regarded as the southernmost city in the world, and from there to strike out into a forest, to find a work that was slowly disintegrating – is perhaps the most important part of this whale’s tale.

“What does it mean to embody a story materially, and then to have that materiality disappear?” asks Christov-Bakargiev, in our book. “This is the space of theatre, of performance, of the stage. This is an attempt to find a form of art able to ground us, to pull us away from digital schizophrenia, to play out the materiality of the world through its constant disappearance, to push our imaginary into the world as a form of embodied film or video, to elaborate and work through the shift from a primarily physical life to a primarily virtual one, because we know that unless this is properly worked through in the early twenty-first century, society will turn towards authoritarian populist regimes as it did in the early twentieth century, ultimately dehumanizing and de-worlding through destruction.”

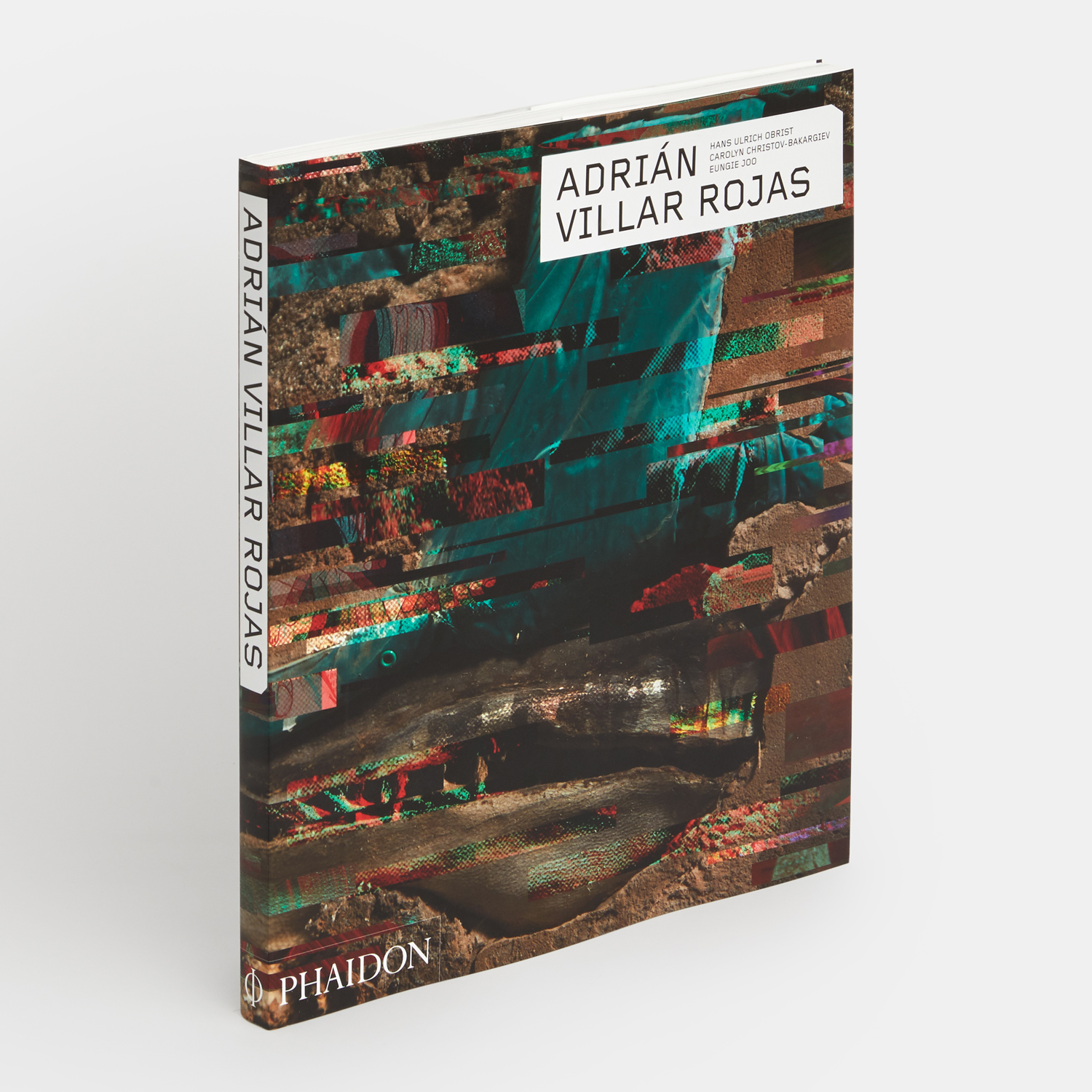

My Dead Family might, in ways, remind us of what it means to truly be alive. To see further pictures and to find out more about this and other works by this crucial contemporary artist, order a copy of our new Adrián Villas Rojas book here.