By scouring the remains of early loos and sewers, archaeologists are finding clues to what life was like in the Roman world and in other civilizations.

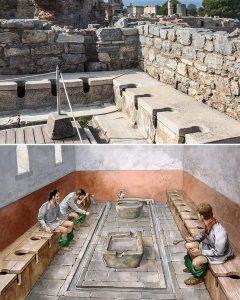

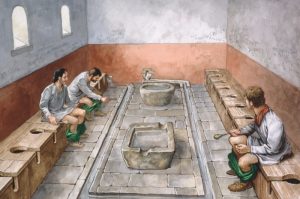

Some 2,000 years ago, a high-ceilinged room under of one of Rome’s most opulent palaces was a busy, smelly space. Inside the damp chamber, a bench, perforated by about 50 holes the size of dinner plates, ran along the walls. It may have supported the bottoms of some of the lowest members of Roman society.

Today, the room is shut off to the public, but archaeologists Ann Koloski-Ostrow and Gemma Jansen had a rare chance to study the ancient communal toilet on the Palatine Hill in 2014. They measured the heights of the benches’ stone base (a comfortable 43 centimetres), the distances between the holes (an intimate 56 cm), the drop down into the sewer below (a substantial 380 cm at its deepest). They speculated about the mysterious source of the water that would have flushed the sewer (perhaps some nearby baths). Graffiti outside the entryway suggested long queues, in which people had enough time to write or carve their messages before taking a turn on the bench. The underground location, combined with the plain red-and-white colour scheme on the walls, implied a lower class of user, possibly slaves.

In 1913, when Italian excavator Giacomo Boni excavated this room, toilets were an unmentionable topic. In his report, he seems to mistake the remains of the holey benches for something much more sensational: part of an elaborate mechanism that, he speculated, would have pumped water and provided power for the palace above. Boni’s prudish sensibilities wouldn’t let him recognize what was before his very eyes, says Jansen. “He couldn’t imagine it was a toilet.”

A century later, toilets are no longer such an unacceptable research topic. Koloski-Ostrow, at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts, and Jansen, an independent archaeologist based in the Netherlands, are among a growing number of archaeologists, infectious-disease specialists and other experts who are shining light on the lost loos of history, from ancient Mesopotamia to the Middle Ages, with a particular focus on the Roman world.

Their investigations have provided a new way to learn about the diets, diseases and habits of past populations, especially those of the lower classes, which have received scant attention from archaeologists. Researchers have inferred that Roman residents ventured into their toilets with some trepidation, in part because of superstition and also because of very real dangers from rats and other vermin lurking in the sewers. And although ancient Rome is famous for its sophisticated plumbing systems, modern studies of old excrement suggest that its sanitation technologies were not doing much for the residents’ health.

“Toilets have a lot to tell us about — far more than how and where people went to the bathroom,” says Hendrik Dey, an archaeologist at Hunter College in New York.

Queen of latrines

Although studies of ancient latrines are no longer off limits, they do take a certain amount of fortitude. “You have to have a very strong sense of self and of humour to work on this topic because one who works on it is going to get ribbed by friends and enemies,” says Koloski-Ostrow. She got started on the topic nearly a quarter of a century ago, when classicist Nicholas Horsfall called her over in the library at the American Academy in Rome. “Latrines. Roman latrines,” he whispered conspiratorially. “No one has done them properly.” She took up that challenge, and now, she says, “I am known widely on my campus as ‘the queen of latrines’.”

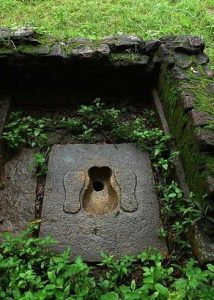

The invention of some of the first simple toilets is credited to Mesopotamia in the late fourth millennium BC1. These non-flushing affairs were pits about 4.5 metres deep, lined with a stack of hollow ceramic cylinders about 1 metre in diameter. Users would have sat or squatted over the toilet, and the excrement would have stayed inside the cylinders with the liquids seeping outwards through perforations in the rings.

Until recently, scholars had little interest in these toilets, says archaeologist Augusta McMahon at the University of Cambridge, UK. “Archaeologists in Mesopotamia have looked at them like, ‘this is a problem: it’s a pit that’s cut into the stuff I’m really interested in’.” As far as she knows, no one has carefully excavated a Mesopotamian toilet yet — something she’s hoping to do when she finds a good candidate and funding.

Mesopotamians themselves also seemed to show little enthusiasm for this revolutionary technology. Although the toilets would have been convenient to use, and cheap and easy to install, they were uncommon, says McMahon, who surveyed the number of latrines in different neighbourhoods for a chapter in a book published last year1. “The number of houses that have toilets is very, very low — one out of five or two out of five,” she says. Everyone else probably used a chamber pot or simply squatted in the fields.

So the health benefits of the technology would have been limited, McMahon says. Although the pit toilets would have successfully separated people from their waste — the measure of a good sanitation system because it prevents the faecal–oral spread of disease — studies by the US Agency for International Development say that some 75% of a population must have access before there are widespread improvements in health.

About 1,000 years later, the Minoans on the island of Crete in the Mediterranean improved the toilet by adding the capacity to flush — although only for the elite. The first known example2 was in the palace at Knossos, says Georgios Antoniou, a Greek architect who has studied ancient sanitation in that country. Water was used to wash the waste from the toilet into the sewer system of the palace.

From there, toilet technology took off. In the first millennium BC, ancient Greeks of the Classical period and, especially, the succeeding Hellenistic period developed large-scale public latrines — basically large rooms with bench seats connected to drainage systems — and put toilets into ordinary middle-class houses. “The society had become more prosperous, and they were dealing more with comfort in everyday living,” Antoniou says.