Beginning in 5300 BC, a Linearbandkeramik or Linear Pottery (LBK) culture developed in the Herxheim region of southwestern Germany, a place that can be described as an idyllic settlement of the period. stoneware. The same houses, the same rudimentary farmland, the small village seemed relatively safe from invaders and predators. However, around 4950 BC, this community suddenly disappeared. The town was abandoned, leaving behind shattered pottery, hundreds of butchered bodies, and a huge pile of bones. Today, researchers are not sure what happened, but signs point to an increase in ritual sacrifice and possibly cannibalism related to it.

Map of the Herxheim site. ( thisbonesofmine.wordpress.com )

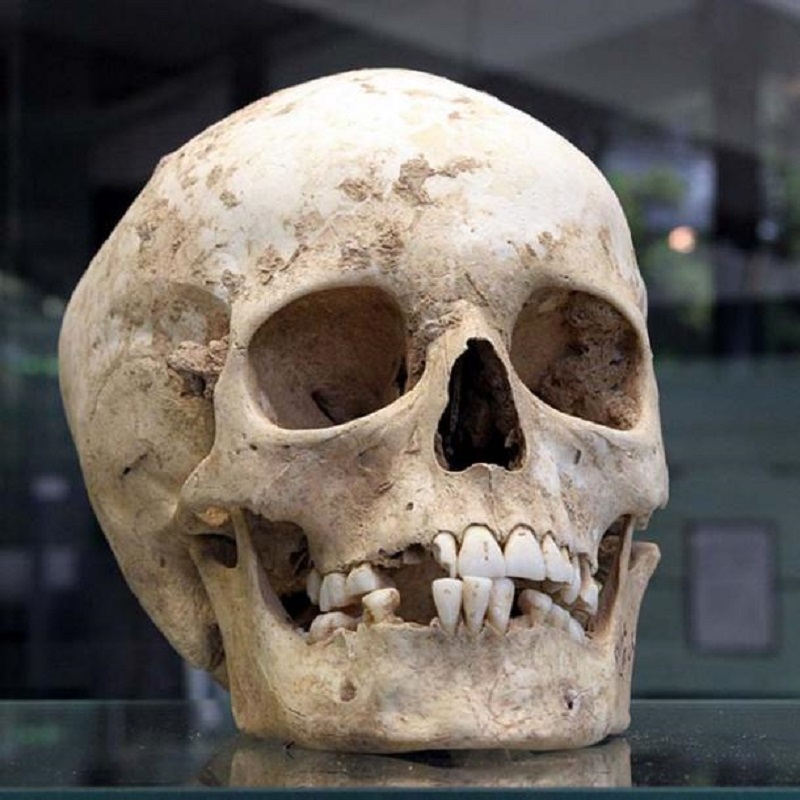

In 2009, an archaeological dig in a Stone Age village discovered a mass grave containing hundreds of human remains, of at least 500 people and possibly more than 1,000 people. The bones are from men, women and children as well as infants and fetuses. Tool marks on the bones show that the flesh was carefully scraped while larger bones were broken, possibly to remove marrow. Even the skull was smashed as if to better extract the brain.

The slaughter all took place immediately after the victim’s death and was clearly done by someone who knew what they were doing. Although the slaughter was carried out with the same practical techniques as slaughtering cattle or sheep, it is uncertain what would become of the human flesh. Some believe that the villagers of Herxheim ate meat; others say it would have been buried with the bones as part of the ritual.

Archaeologists explore the tomb. (museum-herxheim.de)

“We expect the death toll to be twice as high,” said Andrea Zeeb-Lanz, a project leader for the Cultural Heritage Agency working in Herxheim. Such a large number is exceptional for a small village with only 10 buildings. Dating through carbon-14 analysis confirmed that the bones found at the Herxheim site were those of the last known inhabitants of that settlement. However, analysis of artifacts found in the hole showed that the victim was not a native of the village. Indeed, they came from all over Europe, including the Moselle River region (about 62 miles (100km) away) and the Elbe River region (about 250 miles (400km) away). Experts deduced this anomaly through shards of pottery, often very fine pottery, were located between each victim’s ribs. The pottery was exceptionally finely crafted but was deliberately broken into pieces. The shards were as well as stone blades and mortars. Fresh ground was mixed with broken bones and dumped into the pit. The dead were not killed in battle, they were not sick and were not malnourished. Many were not even old.

“One can also imagine that people volunteered to come here and make ritual sacrifices,” Zeeb-Lanz said.

Lead researcher Zeeb-Lanz believes that the answer to the Herxheim mystery lies in the victim’s skull. The crushing of the skull was completed by a skilled hand. After being skinned, each skull was carefully broken to remove the lower part, leaving behind a sort of cap or drinking vessel. Given the fragile nature of human skulls and the basic stone tools available to butchers, only an expert could do this. The skull cap/cup was then carved with intricate symbols. Historians cannot decipher the meaning of these signs, however, it is clear that the people were not killed from starvation. It was part of some kind of ritual, most likely with religious significance. All the skulls were found piled up in one place.

The skull was found at the Herxheim archaeological site. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

“But probably no one drinks from them. Their edges today are still so sharp that people can cut their lips on them, Zeeb-Lanz said. “The more I research, the more mysterious this place becomes.”

Many sensational articles published in Herxheim claimed cannibalism, however, the head of the Zeeb-Lanz excavations warned against such startling conclusions. “We must not forget that this is not a giant settlement. Who is supposed to have eaten all this?”