Demand for gold has increased sharply in recent years, and not everyone is happy about it, especially residents of the town of Grass Valley, California, USA.

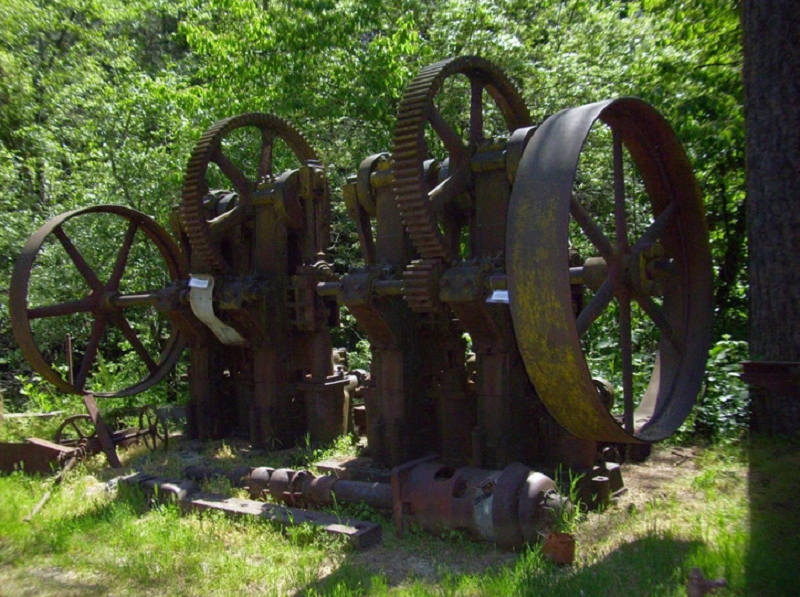

A crusher, once used to crush the gold-bearing rocks of Grass Valley town. Photo: mountain-man-60.blogspot.com

On the outskirts of the town of Grass Valley in Northern California (USA), a giant concrete structure lies alone on weeds and crumbling sidewalks. Nearby, out of sight, is a mine that sinks more than 1,000 meters underground. Those are the remains of the Idaho-Maryland gold mine, a legacy of the town’s gold mining era.

Many mines like these once fueled Grass Valley’s economy, and today, what remains of the Gold Rush is a feature of the town: A crusher, once used to crush gold-bearing rocks, now stands at an intersection on Main Street; Old ore trucks and other rusted remains can be seen in parking lots and storefronts around Grass Valley.

Gold still exists in the abandoned mine’s veins, and Rise Gold, which acquired the mine in 2017, has reason to believe that reopening the mine would make financial sense. When the Idaho-Maryland mine closed in 1956, it wasn’t because gold was running out, but because of economic policy. The Bretton Woods Agreement of 1944 established a new international monetary system that created stability in exchange rates. As part of that effort, the price of gold was fixed at 35 USD/ounce. Gold mining became unprofitable in America.

Today, gold prices are no longer fixed, and prices have increased sharply in response to economic instability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. When the pandemic began, the Federal Reserve Bank (FED) lowered interest rates in an effort to stimulate the US economy and encourage borrowing. But those record low interest rates have reduced returns on bonds and savings, making gold a relatively more attractive investment.

Now, with rising inflation and renewed economic uncertainty due to the Omicron wave, demand for gold remains high. In 2020, about 43% of gold consumed globally went to exchange-traded funds and central banks. As prices rise and mining technology becomes increasingly sophisticated, mines are being reopened in places where mining was once considered economically unviable.

However, gold mining is not as simple as before. The US Geological Survey (USGS) estimates that of the world’s known gold, about 63,000 tons remain in the ground, compared with about 206,000 tons that have been mined. And the world’s untapped gold often lies deeper underground and is therefore harder to access. To get it, companies have to figure out what to do with huge amounts of mining waste, some of which contains heavy metals and other toxic substances.

Rise Gold has committed to minimizing the environmental impact of new mining operations by using a technique called adhesive backfilling, which involves injecting a mixture of water, mine waste and a binder (usually cement) into mining tunnels.

This provides structural support and reduces the amount of mine waste above ground. There are some scientists who advocate the benefits of this approach, but it is only a partial solution and there are still uncertainties about its long-term effects. Many local residents in Grass Valley remain skeptical and concerned about mine waste.

Given these challenges, some economists are questioning whether it makes sense to mine gold when this valuable mineral is only used for bank vaults. “Mining costs are high. There are some profits for the mining company, but a big one is costs,” said financial economist Dirk Baur.

Over the past few decades, proposals to develop or expand gold mining facilities have been put forward across Europe and North America. In Northern Ireland, Dalradian Gold plans to open a mine in the Sperrin Ranges. In Newfoundland (Canada), Marathon Gold plans to open an open-pit mine that the company says will be the largest gold mining operation on the Atlantic coast of Canada.

In the US, which as of 2020 has the fourth largest gold mine reserves in the world, mining operations have expanded in northwestern Arizona in recent years and there are plans to reopen a mine in central Idaho. Many companies are looking to make new fortunes in old locations, facing community opposition similar to what is happening in Grass Valley.

Opponents have good reason to be wary. Mining produces a lot of waste, including ‘waste rock’ and the sludge left behind after gold is extracted from ore. Both waste rock and sewage sludge can contain toxic substances, potentially contaminating ground and surface water.

For decades Grass Valley has had to deal with the effects of Gold Rush-era mining. Arsenic, which occurs naturally in gold mines in the Sierra Nevada foothills, remains an ongoing problem in the region. Old tailings can still leach heavy metals decades after mining operations have stopped. In Grass Valley, authorities recorded high levels of arsenic in a waste pile nicknamed ‘Red Dust Mound’.