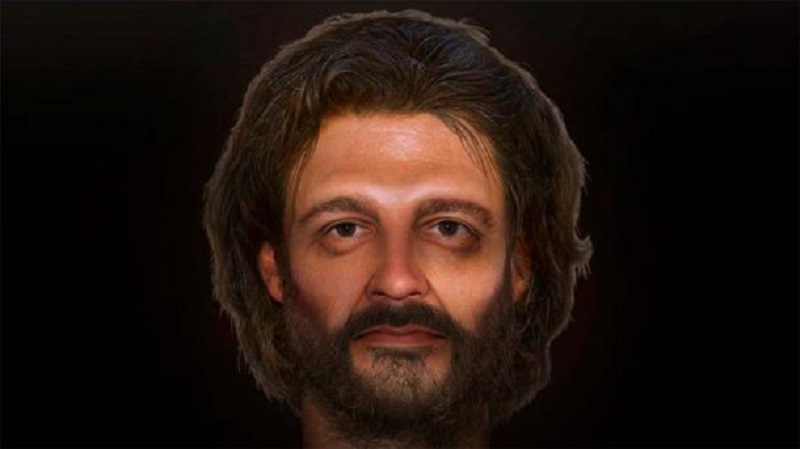

Experts have successfully reconstructed the face of a man who was a victim of Roman crucifixion, a discovery hailed as “almost unique” by Corinne Duhig, a bone expert from the University of Cambridge. best”.

The facial reconstruction was shown on the BBC Four programme, shedding light on the life of a man who met a tragic end at a previously unknown Roman settlement. His skeleton was found at a burial site along with other skeletons from the 3rd and 4th centuries.

“Seeing his face made us respect him more,” Ms. Duhig said.

The reconstruction was carried out by Professor Joe Mullins of George Mason University, Virginia, who described the project as the “most exciting” of his career.

Discover the only evidence of crucifixion in Roman Britain

The practice of crucifixion was one of many “innovations” transported from Rome to Britain after the Roman Empire completed its conquest of the British Isles in the first century AD. This has been established with certainty, after archaeologists working in a small village in Cambridgeshire unearthed an ancient skeleton containing clear and unmistakable signs of having been killed. suffered the cruel and barbaric punishment of crucifixion.

The discovery of the crucified skeleton was announced by the British Journal of Archaeology, but ancient remains were actually recovered during a 2017 excavation in the village of Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire, located 116 kilometers north of London.

The skeleton’s tomb, which is the first evidence of crucifixion in Roman Britain, was found during digging at a future housing development in Cambridgeshire, England. ( Albion Archeology )

Romano-British settlements, cemeteries and crucifixions

While digging at the site of a future housing development, archaeologists from private company Albion Archeology unearthed the ruins of a previously unknown Romano-British settlement. Among other signs of occupation, the site contains five hidden cemeteries containing the bodies of 40 adults and five children. Dating procedures demonstrate that the cemeteries were in use during the third and fourth centuries AD, when Britain was under the control of the Roman Empire.

One of the skeletons unearthed was that of a man, estimated to have been between 25 and 35 years old at the time of his death, who appeared to have been a victim of violence shortly before his last breath.

This wasn’t obvious upon initial examination, but when the skeleton was re-examined in a lab in Bedford, technicians made a chilling discovery. They discovered a metal object embedded in the man’s heel, which was discovered to be a nail that had been driven through the bone.

The first evidence of crucifixion between the Romans and the British was found in Fenstanton, Cambridgeshire, England. A man’s heel was found with an iron nail through the heel bone as clear evidence of crucifixion. ( Albion Archeology )

Based on the nature and severity of this wound, archaeologists know the poor soul was crucified for real or imagined crimes.

Archaeologist Corinne Duhig of Cambridge University, who conducted a thorough examination of the skeleton, said: “The fortunate combination of good preservation and the nail remaining in the bone allowed me to examine this almost unique example where thousands of nails were lost.” BBC .

“This shows that the inhabitants of even this small settlement on the edge of the Empire could not escape Rome’s most barbaric punishment.”

The victim’s face was reconstructed by American forensic artist Joe Mullins. (Unbelievable truth/ BBC )

Radiocarbon testing has revealed that Fenstanton man lived sometime between 130 and 360 AD. The second half of that dating period seems most accurate, as the cemeteries were dated at that time.

In addition to the nail in the heel bone, the man’s leg bones also showed other signs of damage, consistent with him having been chained or shackled. This seemed to give evidence that he had been kept as a prisoner for some time before the final punishment was carried out.

Why is evidence of ancient crucifixions so rare?

Although crucifixion was a common Roman practice, skeletal evidence of it is rare.

When someone was executed in this cruel and deliberate way, their body was often thrown aside or buried in random locations, making it difficult for archaeologists to find. Crucifixion in Rome was a punishment reserved for rebellious slaves, political protesters, and the lower classes, none of whom were of much concern to the Roman authorities when it came time to euthanize them. mourn their bodies.

Additionally, in many cases, crucifixion victims were strung from wooden beams with rope, meaning no nails were needed.

So are there rare skeletons that have clear and unmistakable evidence of having been crucified in Roman times?

According to Corinne Duhig, only three other presumed examples had been reported worldwide at the time of the Fenstanton study. These were excavated at La Larda in Gavello, Italy, at Mendes in Egypt, and in a tomb discovered at Giv’at ha-Mivtar in Jerusalem. Duhig believes that the skeleton found in Jerusalem is the only one that can be identified with 100% certainty as having been crucified, as a nail was also discovered in the heel bone of that unfortunate individual.

In most cases, it appears that the Romans would remove the nails they used in crucifixion before disposing of the body. But in the Fenstanton skeleton, the nail was bent when driven in and thus stuck firmly to the bone.

Archaeologist Kasia Gdaniec, representative of Cambridgeshire County Council’s historic environment team, commented: “Burial practices were many and varied during the Roman period and there is evidence of mutilation before or after death. sometimes seen, but never crucified.” “These cemeteries and the settlement that developed along the Roman road at Fenstanton are breaking new ground in archaeological research.”

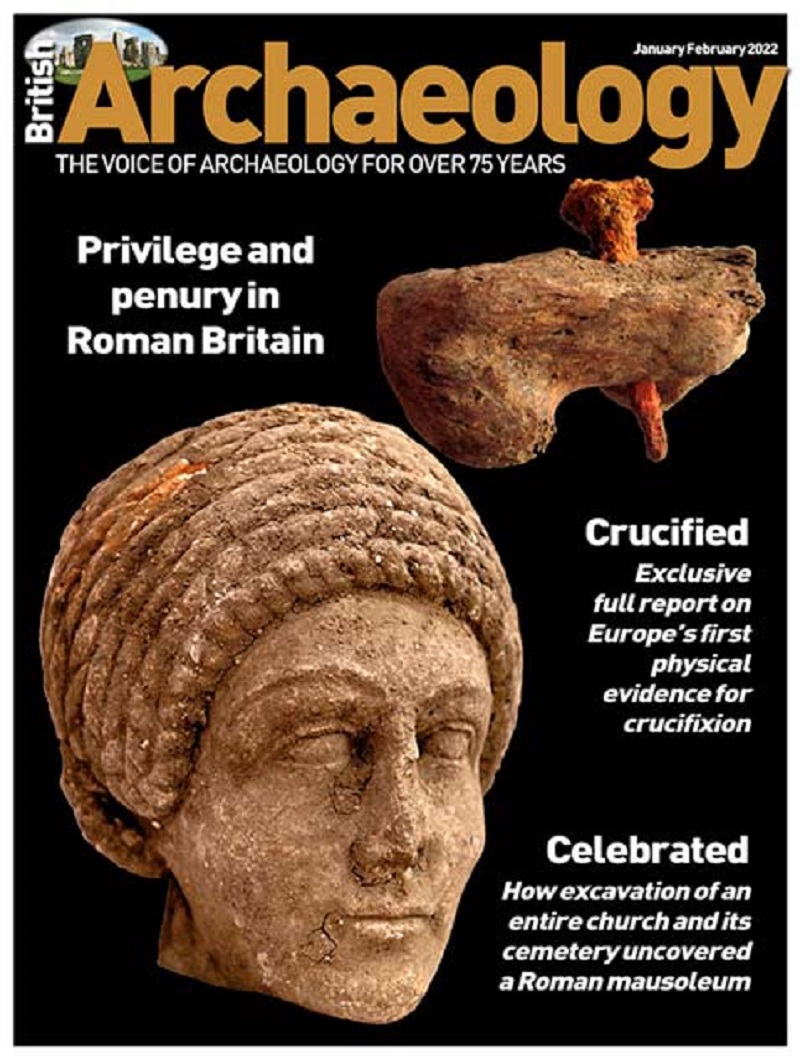

The Romano-British cemetery of Fenstanton and the first evidence of crucifixion in Britain was so important that it appeared on the cover of the prestigious British journal Archaeology. (British Journal of Archeology)

An unknown Romano-British settlement is revealed

News of the crucified remains dominated initial discussions about the excavation at Fenstanton. But Albion archaeological staff have also recovered a number of artifacts left by the Roman-British settlement’s occupants found near ancient cemeteries.

So far, archaeologists have unearthed a horse and rider brooch made from copper alloy, numerous coins, pottery shards with signs of artistic decoration and the remains of cattle bones that appear to have been processed to make personal care items such as soap or bar soap. cosmetics. A large building and leveled surfaces used as courtyards or roads have also been excavated, giving evidence that the Romano-British settlement had advanced infrastructure.

Further excavations will provide more information about how people lived in this unnamed ancient Romano-British settlement. It is known that those who strayed from this ancient village could be sentenced to one of the most terrifying forms of execution ever developed: crucifixion!