Glass’s rich history is being traced using modern archaeology and materials science.

Tracing glassmaking

Another reason why it’s tricky to identify sites for glassmaking is that the process makes little waste. “You get a finished object, and that, of course, goes into the museum,” Rehren says. That led him and archaeologist Edgar Pusch, working in in a flea-ridden dig house on the Nile Delta about 20 years ago, to ponder pottery pieces for signs of an ancient glassmaking studio. The site, near present day Qantir, Egypt, was the capital of Pharaoh Ramses II in the 1200s BCE.

Rehren and Pusch saw that many of the vessels had a lime-rich layer, which would have acted as a nonstick barrier between glass and the ceramic, allowing glass to be lifted out easily. Some of these suspected glassmaking vessels—including a reused beer jar—contained white, foamy-looking semi-finished glass. Rehren and Pusch also linked the color of the pottery vessels to the temperature they’d withstood in the furnace. At around 900° Celsius (1,652° F) , the raw materials could have been melted, to make that semi-finished glass. But some crucibles were dark red or black, suggesting they’d been heated to at least 1,000° Celsius (1,832° F), a high-enough temperature to finish melting the glass and color it evenly to produce a glass ingot

Some crucibles even contained lingering bits of red glass, colored with copper. “We were able to identify the evidence for glassmaking,” Rehren says. “Nobody knew what it should have looked like.”

Since then, Rehren and colleagues have found similar evidence of glassmaking and ingot production at other sites, including the ancient desert city of Tell el-Amarna, known as Amarna for short, briefly the capital of Akhenaton during the 1300s BCE. And they noticed an interesting pattern. In Amarna’s crucibles, only cobalt blue glass fragments showed up. But at Qantir, where red-imparting copper was also worked to make bronze, excavated crucibles contain predominantly red glass fragments. (“Those people knew exactly how to deal with copper—that was their special skill,” Rehren says.) At Qantir, Egyptian Egyptologist Mahmoud Hamza even unearthed a large corroded red glass ingot in the 1920s. And at a site called Lisht, crucibles with glass remains contain primarily turquoise-colored fragments.

The monochrome finds at each site suggest that workshops specialized in one color, Rehren says. But artisans apparently had access to a rainbow. At Amarna, glass rods excavated from the site—probably made from remelted ingots—come in a variety of colors, supporting the idea that colored ingots were shipped and traded for glassworking at many locations.

Glass on the ground

Archaeologists continue to pursue the story of glass at Amarna—and, in some cases, to more carefully repeat the explorations of earlier archaeologists.

In 1921-22, a British team led by archaeologist Leonard Woolley (most famous for his excavations at Ur) excavated Amarna. “Let’s put it bluntly—he made a total mess,” says Anna Hodgkinson, an Egyptologist and archaeologist at the Free University of Berlin. In a hurry and focused on more showy finds, Woolley didn’t do due diligence in documenting the glass. Excavating in 2014 and 2017, Hodgkinson and colleagues worked to pick up the missed pieces.

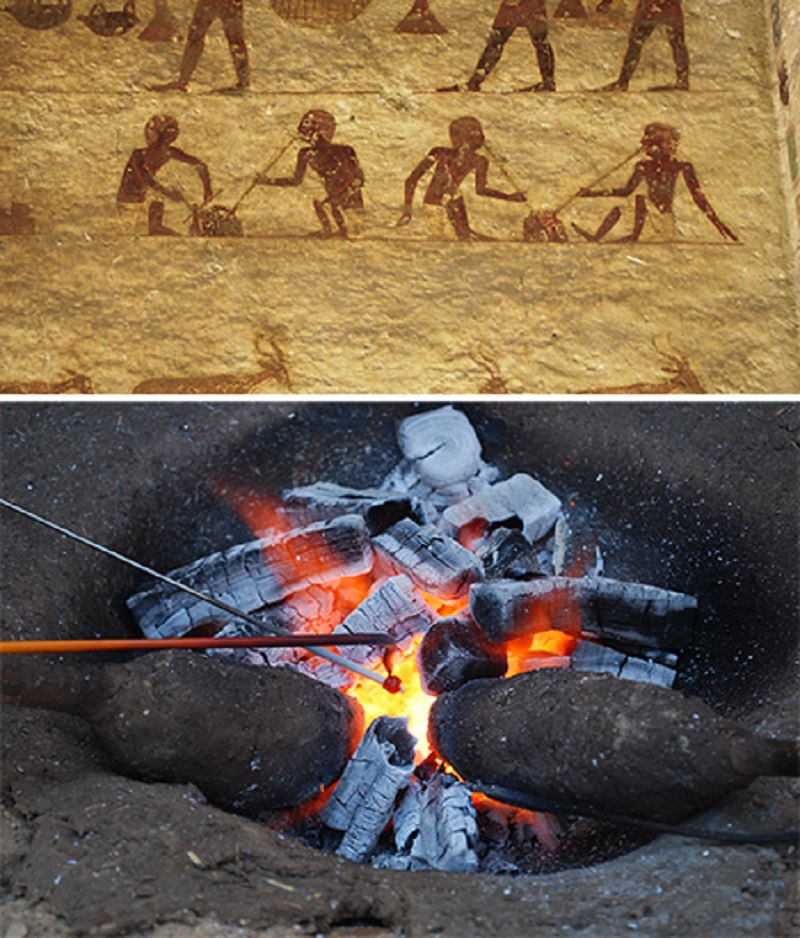

Hodgkinson’s team found glass rods and chips all over the area of Amarna they excavated. Some were unearthed near relatively low-status households without kilns, a headscratcher because of the assumed role of glass in signifying status. Inspired by even older Egyptian art that depicted two metalworkers blowing into a fire with pipes, the archaeologists wondered whether small fires could be used to work glass. Sweating and getting stinky around the flames, they discovered they could reach high-enough temperatures to form beads in smaller fires than those typically associated with glasswork. Such tiny fireplaces may have been missed by earlier excavators, Hodgkinson says, so perhaps glassworking was less exclusive than researchers have always thought. Maybe women and children were also involved, Hodgkinson speculates, reflecting on the many hands required to maintain the fire.

Rehren, too, has been rethinking whom glass was for, since Near Eastern merchant towns had so much of it and large amounts were shipped to Greece. “It doesn’t smell to me like a closely controlled royal commodity,” he says. “I’m convinced that we will, in 5, 10 years, be able to argue that glass was an expensive and specialist commodity, but not a tightly controlled one.” Elite, but not just for royalty.

Researchers are also starting to use materials science to track down a potential trade in colors. In 2020, Shortland and colleagues reported using isotopes—versions of elements that differ in their atomic weights—to trace the source of antimony, an element that can be used to create a yellow color or that can make glass opaque. “The vast majority of the very early glass—that’s the beginning of glassmaking—has antimony in it,” Shortland says. But antimony is quite rare, leading Shortland’s team to wonder where ancient glassmakers got it from.

The antimony isotopes in the glass, they found, matched ores containing antimony sulfide, or stibnite, from present-day Georgia in the Caucasus—one of the best pieces of evidence for an international trade in colors.

Researchers are continuing to examine the era of first glass. While Egypt has gotten a large share of the attention, there are many sites in the Near East that archaeologists could still excavate in search of new leads. And with modern-day restrictions on moving objects to other countries or even off-site for analysis, Hodgkinson and other archaeologists are working to apply portable methods in the field and develop collaborations with local researchers. Meanwhile, many old objects may yield new clues as they are analyzed again with more powerful techniques.

As our historical knowledge about glass continues to be shaped, Rehren cautions against certainty in the conclusions. Though archaeologists, aided by records and what’s known of cultural contexts, carefully infer the significance and saga of artifacts, only a fraction of a percent of the materials that once littered any given site even survives today. “You get conflicting information, conflicting ideas,” he says. All these fragments of information, of glass, “you can assemble in different ways to make different pictures.”

Carolyn Wilke is a Chicago-based freelance science journalist who is fascinated by how chemistry and materials intersect with societies both ancient and modern. Find her on Twitter @carolynmwilke.

This story originally appeared on Knowable Magazine.