The city of Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic, is known for many things. But one aspect of its history is often overlooked – it was a major center of occult and dark arts in the 16th century. Evidence for this side of Prague emerged when the discovery of a The old building appears to have been an alchemy laboratory in 2002 – Speculum Alchemiae.

Explore Speculum Alchemiae

In 2002, the city of Prague suffered a terrible flood that left 30,000 people homeless and at least 16 people killed. During the cleanup after the flood, a house in the Jewish quarter was found that contained several underground experimental facilities dating back to the 16th century. Further examination of the building led searchers to seeing it believed it was an alchemy laboratory.

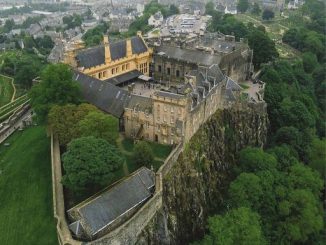

The exploration includes alchemy workshops with equipment and a network of underground tunnels connecting three important locations in Prague – the Old Town Hall, the Barracks and Prague Castle.

The house is now the site of an alchemical museum, Speculum Alchemiae.

‘Alchemy.’ The Speculum Alchemiae Museum in Prague shows the mystical side of the city. Source: CC0

In the 16th century, Prague was the domain of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1552-1612). Rudolf II is known as a great patron of arts and sciences. He was named Holy Roman Emperor in 1576 and ruled the city of Prague in 1583. Until his death in 1612, Rudolf II helped make Prague one of the centers of scientific research and leading art production in Europe. He hosted some of the most important scientists, philosophers, and artists on the continent at the time. Some famous scientists who worked in Prague under his patronage were astronomers Tycho Brahe (1546-1601) and Johannes Kepler (1571-1630).

Portrait of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II (1590s) by Hans von Aachen. (Public domain)

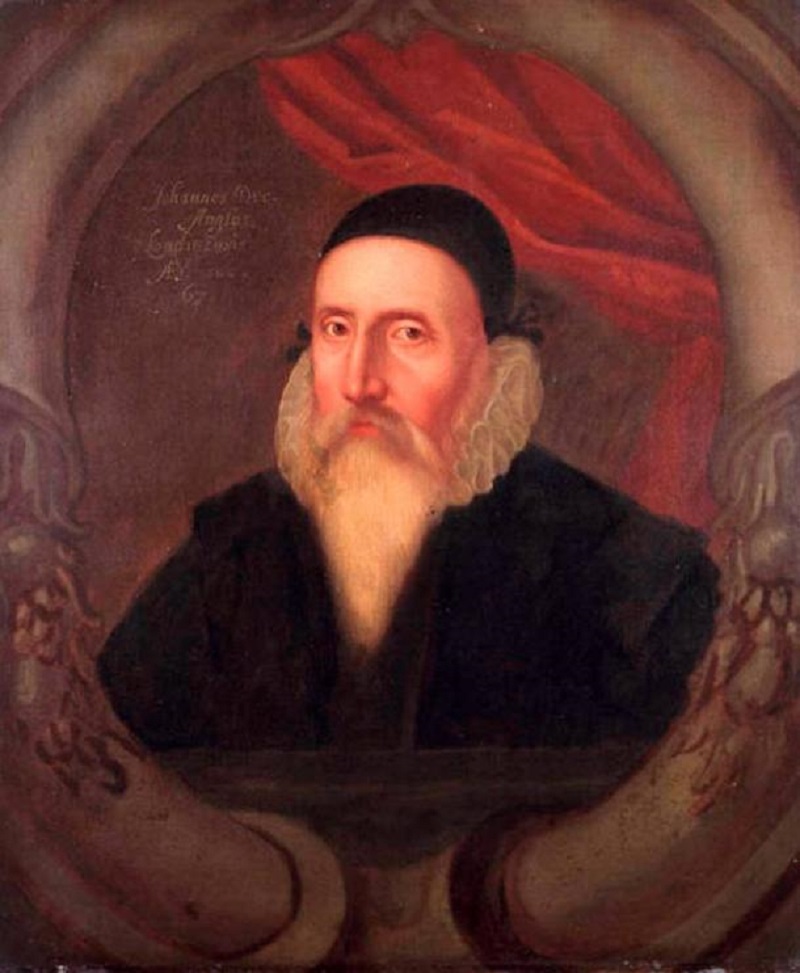

In addition to the emperor’s interest in science, he also showed interest in the occult. Rudolf II was a patron of alchemists and was associated with famous magician-type figures such as John Dee and Edward Kelley. This 16th-century laboratory seems to have been the result of the emperor’s interest in the mysteries of the hidden wisdom of previous ages.

Rudolf II: Science enthusiast and occultist?

Today, there is a clear separation between what is considered science and what is considered mystical and magical. Alchemy, astrology, and similar disciplines are considered pseudoscience by scientists today. However, in the 16th and 17th centuries, there seems to have been less separation between science and mysticism. Many figures considered great scientists today were also fascinated by the occult. For example, Johannes Kepler was also an astrologer. Isaac Newton, in addition to his revolutionary contributions in the field of classical mechanics, also devoted most of his life to studying alchemy. Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry, was also heavily influenced in the thinking of earlier alchemists.

On the other hand, John Dee, famous as an alchemist and mystic, was also a brilliant mathematician and astronomer who also worked in the field of navigation. These are all pursuits that today are considered legitimate science.

Portrait of John Dee. (Public domain)

As a result, it is possible that Rudolf II did not notice the great difference between his interest in astronomy and mathematics on the one hand and his advocacy of alchemy and astrology on the other. and mysteries. He, like many intellectuals at the time, could see them as the mundane and fantastical sides of the same spectrum. They all pursue science.

Secret reason

Although alchemy and similar disciplines were considered legitimate sciences at the time, there were still some risks in practicing them. Interestingly, Rudolf II chose to build this alchemical experimental facility in the Jewish quarter. Maybe the reason for this is that in some ways Judaism at that time was more friendly to the occult sciences than Christianity. So building it there would cause less suspicion.

Part of Speculum Alchemiae. (Steven Feather/ CC BY NC SA 2.0 )

The legacy of alchemy

Alchemy is no longer accepted as a scientific view of nature, but there is growing historical evidence that early alchemists made useful contributions to science and laid the foundations for the foundations of later fields such as physics and chemistry. Although alchemists did not always understand the results of their experiments, alchemical experiments sometimes produced interesting and practical discoveries.

An example is the philosopher’s tree – the result of an alchemical experiment that created a tree-like golden structure. A chemist and historian of science at John Hopkins University, Lawrence Principe, used alchemical texts and notebooks to repeat the experiment and was able to create the philosophical tree.

A well-developed Diana plant (Philosopher’s plant) grows on a copper rod from a silver/mercury amalgam placed in a 0.1 M silver nitrate solution – reaction time 2 hours. ( CC BY SA 4.0 )

Alchemists did not succeed in turning base metals into gold, but they may have been on to something even if they didn’t realize it. It is possible that alchemy was a primitive science in the 16th century, a precursor to a formal scientific field, rather than a pseudoscience. This made the alchemy laboratory a precursor to the science laboratory. Instead of reaching a dead end, the work of medieval alchemists paved the way for the work of modern chemists.