Homer’s Iliad is often considered one of the greatest works of Western literature. For centuries, Homer’s Troy, the city besieged by the Greeks, was considered legendary by scholars. However, during the 19th century, one man embarked on a journey to prove that this legendary city actually existed. This is German archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. He was successful in his mission and Hisarlik (the site Schliemann excavated) is today recognized as the ancient site of Troy. Among the artifacts unearthed at Hisarlik was the so-called ‘Treasure of Priam’, which, according to Schliemann, belonged to the Trojan king, Priam.

Discover Priam’s treasure

In 1871, Schliemann began excavating the Hisarlik site. After identifying the level known as ‘Troy II’ as the Troy of the Iliad, his next goal is to discover the ‘Treasure of Priam’. Since Priam was the ruler of Troy, Schliemann reasoned that he must have hidden his treasure somewhere in the city to avoid capture by the Greeks if the city fell. On May 31, 1873, Schliemann found the precious treasure he was looking for. In fact, Schliemann found the ‘Treasure of Priam’ by accident, as he is said to have seen gold on the surface of the trench while straightening the edge of a trench to the south-west of the site.

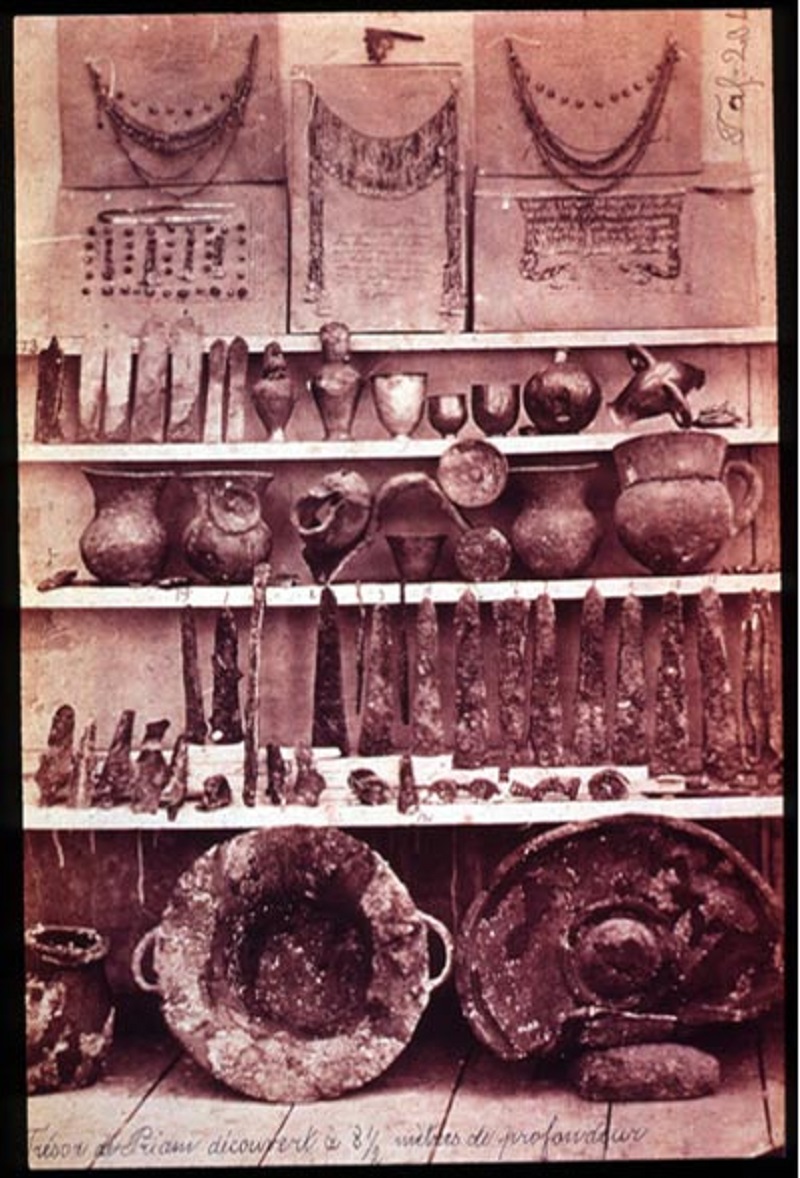

Items from the trove of Troy II (“Priam’s Treasure”) discovered by Heinrich Schliemann. (Wikimedia Commons)

A treasure trove of gold

After removing the treasure from the ground (the objects were tightly packed and Schliemann reasoned that they had once been placed in a rotting wooden chest), Schliemann locked his finds in the wooden house mine. In addition to gold and silver objects, the ‘Treasure of Priam’ also contained several weapons, a bronze cauldron, a shallow bronze pan and a bronze kettle. Although Schliemann reported that the ‘Treasure of Priam’ was a single find, others have doubted this claim, arguing that it was a mixture, with the most important objects discovered in May 31, 1873, while other objects were discovered at a different time. days earlier, but was added to the treasure chest nonetheless.

Bold plan to keep the treasure out of Ottoman hands

Regardless of the nature of the ‘Treasure of Priam’, the Ottoman government still wanted to get its hands on it. However, Schliemann had other plans and came up with a plan to get the artifacts out of Ottoman territory. How Schliemann achieved this feat remains a mystery and there has been much speculation over the years. For example, one legend attributes Schliemann’s successful work to his wife, Sophie, who smuggled the artifacts through Ottoman custom by hiding them in her underwear. Schliemann was eventually sued by the Ottoman government. He lost the case and was fined 400 pounds as compensation to the Ottomans. However, Schliemann voluntarily paid £2000 instead, and it has been pointed out that this increase may have secured him something additional, although exactly what this is is unclear.

Portrait of Sophia Schliemann wearing some of the Priam Treasures ( Wikimedia Commons ). It is believed that she helped smuggle her husband’s belongings out of the country by hiding some of the treasure in her underwear.

Find a home for Priam’s treasure

After discovering the ‘Treasure of Priam’, Schliemann searched for a museum to display it. Meanwhile, valuable artifacts were being stored in Schliemann’s house, making him extremely worried. It was in 1877 that ‘Priam’s Treasure’ was displayed to the public for the first time at London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). After being displayed for several years in London, ‘Priam’s Treasure’ was then transferred to Berlin in 1881. From 1882 to 1885, the objects were temporarily displayed in the Kunstgewerbe Museum, before being transferred to the newly built Museum of Ethnology.

One of the treasures of the Priam treasury. Golden crown with “idol” pendant ( Wikimedia Commons )

In the following decades, ‘Priam’s Treasure’ was housed at the Berlin Museum of Ethnology. However, after the defeat of Nazi Germany and the end of World War II in 1945, the artifacts disappeared. It is suspected that the Soviet troops occupying Berlin were responsible for bringing the treasure as well as countless other valuable artifacts and works of art back to Moscow. Possession of the ‘Treasure of Priam’ was denied by the Soviet Union until 1993, when it was first officially acknowledged that the treasure was actually in Russia. Today, ‘Priam’s Treasure’ still resides in Russia. While the Russians considered the treasure to be booty to compensate for their losses in World War II, the Germans considered it looted goods and demanded its return.