When a Colombian sugar plantation worker and his tractor plunge into a hole that suddenly opens in the ground, the spectacular discovery buried underground will lead to a looting, murderous rampage. on a large scale and destroyed ancient artifacts and tombs from there. a rich, mysterious, unknown culture.

This is the story of the Malagana Treasure.

In 1992, a sugarcane farm worker was working in the fields at Hacienda Malagana located in the municipality of Palmira in Colombia’s Cauca Valley. The ground gave way, and both man and machine fell into the hole. As the worker tried to solve his predicament, he noticed shiny yellow objects on the ground. Upon closer inspection, he realized he had found treasure and did not tell anyone, instead choosing to hide the valuable objects for himself.

This man didn’t know much, but he had just removed ancient, priceless gold artifacts from burial mounds and objects of a previously unknown indigenous culture of Colombia .

Gold fever

The clerk sold objects that might have come from the newly found graves, but his secret did not last long. When other employees and locals learned there was treasure buried in the field, the news spread like wildfire and a looting frenzy began. Between October and December 1992, around 5000 people are said to have visited Hacienda Malagana in what has been described as the “Malagana Gold Rush”. The Hypogeum was ruthlessly and thoroughly plundered by gold seekers, and it was reported that at least one person was murdered. Nearly four tonnes of pre-Columbian artifacts have been taken off the site to be melted down or sold to collectors in what has been ruefully described as “the largest haul since the early conquests ”. Hundreds of graves were destroyed in the process.

“Stylized cat nose decoration from Malagana 200BC-200AD as part of the exhibition “The Spirit of Ancient Colombian Gold”. While wearing this large nose ring, a magician transformed into a jaguar. Powerful predators, jaguars symbolize power and status.” (David, Flickr/ CC BY 2.0 )

It was not until January 1993 that authorities were alerted to the looting in Malagana. According to reports, reporters present at the scene recorded the chaos on camera and posted photos in the newspaper. Police at the scene were unable to contain or control the chaos, prevent looters from fighting each other, and were unable to protect the site from widespread destruction.

It is not known how many irreplaceable artifacts were lost to private collections or simply melted down for gold.

Malagana was one of four societies that made up the Calima culture. Calima Cultural Golden Mask, Gold Museum, Bogotá, Colombia. ( CC BY 2.0 )

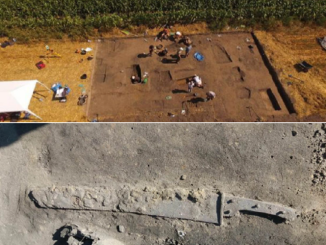

Rescue excavation

Beginning in March 1993, archaeologists from the Instituto Vallecaucano de Investigaciones Científicas (INCIVA) and the Instituto Colombiano de Antropología (ICAN) attempted to excavate the site, but looters kept interrupting the work. and the security situation is still difficult, so research has to be paused. . By 1994, the treasure hunters had given up and archaeologists were finally able to learn more about the mysterious culture.

Research indicates that the inhabited site dates from 300 BC to 300 AD.

Because the cemetery was largely destroyed, the researchers focused their attention on the residential area about 500 meters (1,640 feet) away.

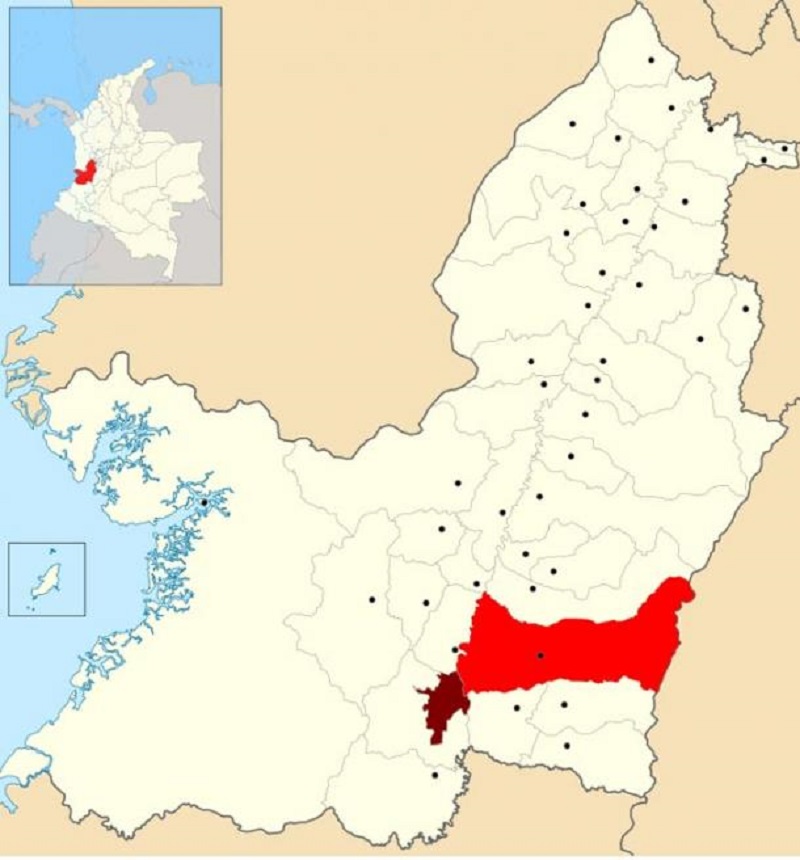

Malagana is located in the municipality of Palmira, Valle del Cauca of Colombia. ( CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Malagana culture

Because this site was found under the sugarcane growing area of Hacienda Malagana, the cultural complex was discovered underground and the unknown people were so named. The Malagana people were one of four societies that successively occupied the valley and created the Calima culture (200 BC – 400 AD). Calima culture includes Llamas, Yotoco, Sonso and Malagana.

Calima Cultural Golden Ceremonial Tweezers. Men in ancient Colombia used tweezers to pluck facial hair. This complex pair may have been used in rituals or ceremonies. Simpler versions of these tweezers would have been used on a daily basis. Gold objects were created throughout ancient America for the exclusive use of the ruling class, priests, and other nobles. Acquired by Henry Walters, 1910. ( Wikimedia Commons )

In “Women in Ancient America: Second Edition,” authors Karen Olsen Bruhns and Karen E. Stothert write that the Malagana people flourished in their settlements located in swamps and farmlands fertile. The remaining artifacts and ceramic patterns in the tombs of this culture suggest to researchers that the Malagana people lived in rectangular stilt houses.

Bruhns and Stothert write that some excavations have revealed ceramic offerings depicting women, perhaps shamans. In the sculptures depicting young women, each statue contains a rock crystal.

Crab-shaped boat (alcarraza), Malagana, Colombia. (Beesnest McClain, Flickr/ CC BY 2.0 )

Possessing a distinct iconic style, Malagana crafts high-end ceramics, mainly in white or terracotta. They made large bottles, jugs with double spouts and wind instruments, ocarinas. Their gold and silverware is clearly outstanding as judged by reports from looting witnesses and the surviving artifacts today in museums.

It belongs to the Museum

Bogotá’s Museo del Oro said it recovered several gold objects looted from Malagana in late 1992. About 150 pieces of Malagana gold were eventually bought back, with nearly 500 million pesos ($300,000) saved by the museum. pay looters in conservation efforts. artifacts. The move was criticized by some as encouraging looting of sites and trafficking in artifacts. However, with the rescued artifacts and information from researchers, 29 Malagana tombs from the hypogeum were reconstructed and the context established.

Other museums have also tried to salvage some artifacts, if only by taking photos of the artifacts to document the lost Malagana.

Calima Cultural Sculpture, Gold Museum, Bogotá, Colombia (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Unfortunately, looting at Hacienda Malagana has continued since the initial landings in 1992 (although the numbers have decreased) and cases of digging were reported as recently as 2012.

The sad reality of looting

In “Handbook of South American Archeology,” Helaine Silverman and William Isbell note with dismay that in Peru alone, “more archaeological sites have been destroyed since World War II than in the first 400 years after the Spanish conquest. And destruction is increasing, whether through looting, economic development (e.g. agricultural development, irrigation projects) or population resettlement.”

Sadly, such looting and destruction continues to this day across the globe.

Cemeteries and cultural artifacts may have been plundered, but gradually they are making their way to museums, and researchers are diligently preserving and protecting the cultural heritage of ancient peoples. era was lost in Malagana.