It isn’t rare for a once prosperous medieval town to be abandoned and slowly get side-lined in the annals of history. Nothing exemplifies this statement better than the lost Viking village of Borgund, on the west coast of southern Norway.

The Discovery of the Viking Village of Borgund, Norway

The Borgund Kaupang Project was launched in 2019 by the University of Bergen to re-examine the millions of Viking village artifacts found in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, which have long been housed in a basement archive, according to Science Norway.

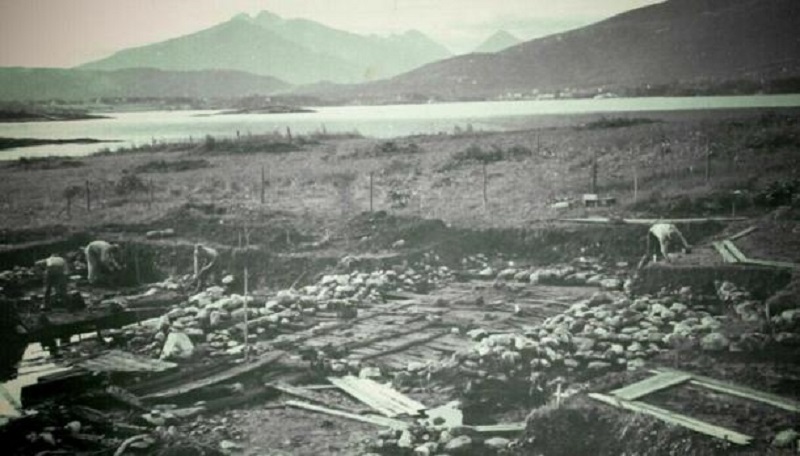

This picture shows the Borgund Viking village excavation site in 1954. The Borgund fjord, a rich source of code, can be seen in the background. (Asbjørn Herteig / University Museum of Bergen / CC BY-SA 4.0)

At the time of discovery in 1953, a piece of land near Borgund church had been cleared, uncovering a lot of debris and objects that were immediately traced to the Norwegian Middle Ages. Over the course of that year and the following summer some 45,000 objects were painstakingly put away into storage after a cumbersome excavation. It was only in 2019 that these items were taken out of storage to piece together the history of a thousand-year-old Norwegian Viking village that the world knows little about.

The 45,000 objects from the 5,300 square meter excavation area in Borgund have just been lying here,” said Danish archaeologist and project manager Professor Gitte Hansen. “Hardly any researchers have looked at this material since the 1970s.”

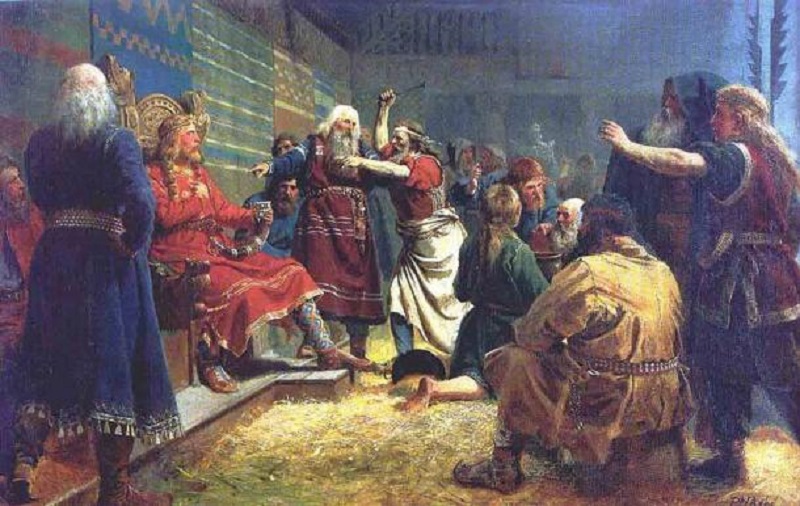

What’s particularly interesting is that the town of Borgund is mentioned in Viking sagas and charters from the Middle Ages. Sagas mention the existence of the town as early as at least 985 AD, as this was where Håkon Jarl and his sons journeyed before the battle against the Jomsvikings in 985 AD, states the University of Bergen (UIB) press release. King Håkon was the de facto Norwegian ruler between 975 and 995 AD.

King Håkon the Good, who visited the Viking village of Borgund, during his reign, overseeing a peasant dispute in a painting by Peter Nicolai Arbo. (Peter Nicolai Arbo / Public domain)

Reconstructing Borgund’s Viking History From Written Sources

From a historical point of view, sagas are always taken with a pinch of salt. The reasoning for this is twofold.

First, sagas are semi-legendary or legendary in nature, bordering on mythology, and have a tendency to conflate the king’s association with gods. For example, this saga associated King Håkon’s lineage with Sæming, son of Odin.

Second, revisionist history writing is cautious in accepting verbatim sources that are issued from the perspective of those at the apex of society, who are never fair or judicious with their representations of reality. This is largely due to the assertion of power and prestige that comes with the burden of disparately designed social hierarchies.

Then there is a reference to Borgund in relation to the Battle of Bokn in 1027 AD, which has been accepted by this group of scholars and researchers as the oldest written evidence for the existence of the Viking village.

The limited sources written about Borgund in the Middle Ages refer to it as one of the “small towns” (smaa kapstader) in Norway. “Borgund was probably built sometime during the Viking Age,” adds Professor Hansen, who is also head of the Department of Cultural History at UIB.

Here lies the remnants of the forgotten Viking village of Borgund. (Bård Amundsen / sciencenorway.no)

Difficulty in Reconstruction and Moving Forward

Within a hundred odd years, Borgund became the most expansive Viking village on the west coast between Trondheim and Bergen. It flourished till the mid-14th AD, when it was actually at its peak.

However, the plague defined Europe in the Middle Ages had a terrible impact on Borgund, to such an extent that by the end of the 14th century AD, Borgund disappeared from the annals of history. This coincided with the Little Ice Age which left much of northern Europe much colder and snowier than before.

Unfortunately, the recovered Borgund Viking village textiles (250 pieces in total) have suffered as no conservation effort was made to preserve them, apart from leaving them in storage. Yet, Hansen admits that she is rather grateful for even having the tattered fabrics to hold onto. Credit for the excavation in 1953 and ’54 goes to Asbjørn Herteig, one of the pioneers of modern medieval archeology.

Herteig’s strength lies in subverting historical interests from important buildings and centers of power like churches, monasteries, and castles. His method was to assemble a meticulous collection of seemingly trivial artifacts. This included shoes’ soles, pieces of cloth, slag, potsherds (ceramic and otherwise), to name a few, that helped piece together the lives of ordinary people.

The unfinished Borgund Viking village investigations indicate a dense settlement of houses and at least three marble churches. The nearby fjord, known as Borgundfjordfisket, was a rich cod fishery that harvested in late February and early March. The inhabitants ate a lot of fish, as proven by the millions of fish bones, and fishing gear artifacts found at the site.

The Borgund Viking village was probably created in the 10th century AD, and there is evidence of trade and contact with the rest of Europe, particularly Western Europe. Numerous pieces of English, German, and French tableware were found at the site. An exchange of art, music, and fashion also occurred. The last official mention of Borgund was from 1384 AD, in a royal decree which involved the farmers of Sunnmøre to buy their goods in the market town of Borgund.

Financed by the Norwegian Research Council, the ambitious and historically crucial documentation of Borgund Viking village has been captured in detail on the official Facebook page of the BKP and the Per Storemyr Archeology and Conservation Group page. A five-part documentary series has been prepared by the BKP and can be accessed here. The BKP team includes archaeologists, geologists, osteologists (bone experts), metal scientists, and art historians.