There is a certain perception of the Great Pyramid as a completely empty arrangement of empty halls and rooms, strangely lacking artifacts and inscriptions that might provide clues to its construction. However, in 1992, German engineer Rudolf Gantenbrink and his team gave modern-day viewers their first glimpse of the Great Pyramid’s original metal artifacts by sending a rover compactly into the southern axis of the Queen’s Chamber.

The probe’s endoscopic camera revealed a limestone monolith, a ‘door’ fitted with a pair of bronze fixtures or pins whose purpose is still debated. However, these pins are not the only pieces of metal found inside the Great Pyramid that are believed to be original to the structure. Indeed, when the 19th-century British explorer and civil engineer Waynman Dixon first identified the north and south axis of the Queen’s Chambers in 1872, he also discovered a trio of other artifacts. often, seemingly unrelated. These have come to be known as the Dixon Monuments.

Granite hooks and balls were recovered in the Great Pyramid by Dixon and Grant in 1872. (F lanker / Public Domain )

In 1872, after Dixon and his colleague Dr. James Grant chiseled their way into the sealed Queen’s Chamber shafts, they installed a stick into the north shaft. Like its southern counterpart, the northern shaft penetrates the wall seven feet before tilting upward. Dixon’s probe managed to loosen three objects amid the rubble in the shaft: a bronze grappling hook, a granite ball and a short stick described by Dixon as ‘resembling a cedar’.

The objects were returned to England, where their discovery attracted much interest before they eventually disappeared from the records. For nearly a century, researcher Robert Bauval later learned that the relics remained in the possession of the Dixon family, and in 1972, Dixon’s great-granddaughter donated the objects to the British Museum, where they once again disappeared, only to reappear in 1993 thanks to Bauval’s arduous efforts. However, the cedar stick is still inexplicably missing.

The Queen’s Chamber shaft where the Dixon relics were discovered. (Bakha~commonswiki / Public Domain )

What is the Dixon Monument?

The remote location of the artifacts inside the pyramid seems to leave little doubt that they were placed at the time of the pyramid’s construction. So what exactly are those objects and what are they doing in the axis? The 19th-century pyramidologist Charles Piazzi Smyth, Dixon’s friend and correspondent, speculated in 1877 that the objects were primitive tools made by enslaved pyramid builders. slaves were accidentally released into the shaft (although today we know that slaves did not participate in the construction of the pyramid).

An article in the journal Nature in the year of the discovery proposed that the granite ball was a standard Egyptian weight ball, with a rough concavity on one side, reused as hammers, and wooden sticks. The cedar, carved with a file, may have originally been attached to a bronze hook to form a tool. For 19th century explorers, speculation was short lived.

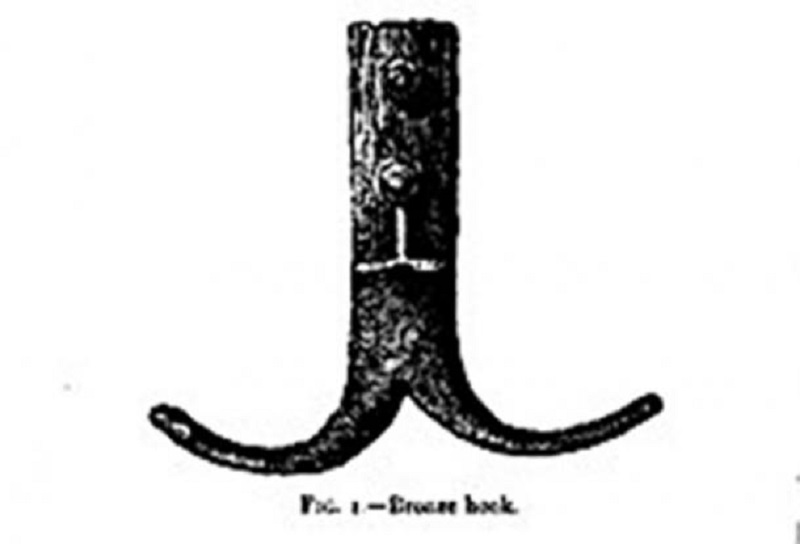

Dixon Relic – bronze hook found inside the Queen’s Chamber vault. (Nature, Volume 7 / Public Domain)

Dixon Relic – piece of cedar found inside the Queen’s Chamber vault. (Nature, Volume 7 / Public Domain)

The resurfacing of the artifacts in the 1990s sparked new theories regarding the artifacts. Some modern-day researchers have begun to suggest that these objects were not lost as leftover debris from pyramid construction but were placed on purpose with ceremonial precision. by priests or architects. Citing Czech Egyptologist Dr. Zbyněk Žába and Oxford University’s Dr. IES Edwards, Robert Bauval and Adrian Gilbert proposed in their groundbreaking work The Orion Enigma that the bronze hook resembled a pesh-device. en-kef (pesesh-kef, elsewhere) used in funeral rituals wepet-er (opening of the mouth) would release the jaws of the deceased king and allow him to eat, drink and breathe in the afterlife that .

Furthermore, this ritual is reflected in the alignment of the northern axis with the constellation Ursa Minor. As Bauval and Gilbert argued in a later article, Ursa Major, the companion of Ursa Minor was involved in the ‘mouth opening’ ritual in the Pyramid Texts, in which an instrument resembled the constellation , an adze, was used by Horus to open the dead pharaoh’s mouth. So is there any connection between the tool found in the north axis and the tool in the sky?

The most intriguing connection seems to be the adze, the tool often used in conjunction with the pesh-en-kef during the ‘opening of the mouth’ ceremony. Not only is Adze shaped like the constellations Ursa Major, or ‘thigh’, and Ursa Minor, but the Egyptian word khepesh, akin to pesh-en-kef, refers to the leg of an ox (inversion The hieroglyphic reverse of khepesh also refers to strength or power, qualities bestowed on the deceased by pesh-en-kef during the ‘opening’ ceremony).