A bas-relief from the 11th dynasty currently on display in the Louvre, pictured below, depicts a butchered leg of ox with a shape that clearly resembles the fish tail of pesh-en-kef, suggesting that pesh- The fishtail en-kef, the ceremonial adze and the northern sky Constellation ‘thigh’ carry a deep and complex connection. However, an adze companion to the Dixon hook has not yet been discovered in the shaft.

Abkaou receiving gifts, 11th dynasty, Louvre Museum. (Rama / BY-SA 2.0 FR )

The pesh-en-kef theory is not without question. One might ask, as Egyptologist Stefan Bergdoll did in his extensive study of the Dixon artifacts, why a pesh-en-kef device of apparently atypical workmanship was placed inside the shaft when Other devices, like the elaborate model in the photo below, have survived since then. the first dynasties of the Old Kingdom. One can speculate that the Dixon object may have been a much more ancient and therefore precious pesh-en-kef device left inside the pyramid for preservation as well as ritual performance, but they we have examples of these devices being made from the Predynastic period. stone and not similar to the metal Dixon hook.

These first flint devices were sharpened and used to cut the umbilical cord during childbirth, and it was from these fish-tail devices that the stylized pesh-en-kef of the Old Kingdom developed for religious purposes. is to ‘cut’ or release the soul from it. body after death. Despite the similarity in shape, both the predynastic flint device and the later stone pesh-en-kef device were identical to the Dixon hook, but there was another important function attributed to Egyptian fishtail tools: astronomical observations.

Model of ‘open mouth’ ritual tool. (Paros / Public Domain)

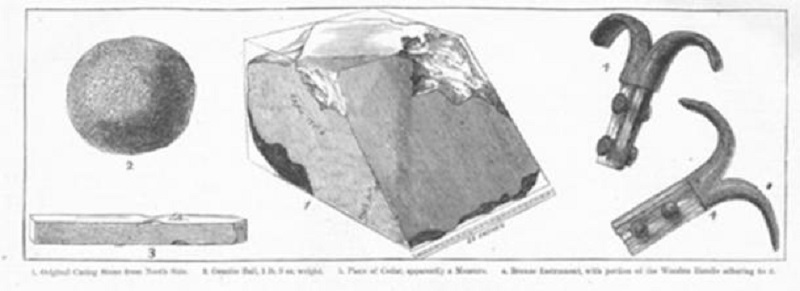

Crichton E.M. Miller, who wrote extensively on the astronomical significance of the Dixon artifacts, using the work of Dr. Zbyněk Žába as a basis, believes that the bronze grappling hook may have been used in conjunction with the ball granite to form the master craftsman’s plumb line tool. capable of surveying, timekeeping, navigation, and making astronomical measurements used to align the pyramid.

In 1956, Dr. Žába became the first person to find a connection between the pesh-en-kef double hook and the Egyptian astronomical device known as the merkhet, the ‘instrument of understanding’ that incorporated an closely matches a plumb line, bar and line. He showed how the merkhet was used to align a temple or pyramid with the polar stars, and he suggested that the shape of the pesh-en-kef devices of the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods The modern is significantly applicable to use as an observation tool and can be understood as an early form of the V-shaped observation tool later known as the bay.

If the Dixon relic did indeed form a merkhet, this would explain the lack of stylization of the Dixon hook compared to pesh-en-kef devices of the time. Furthermore, this would make the Dixon hook not an idealized model but an actual observational tool used in conjunction with other pieces to align the pyramid with the pole stars, such as Bauval and Gilbert initially proposed. If this is correct then the tool would possess some form of ritual significance, which would explain its location on the north axis.

Finally, the exact nature of the dorsolateral shape shared between pesh-en-kef and Old Kingdom observables remains unclear. However, it is clear that the Dixon tool may have been astronomical in nature and that any ceremonial connection with funeral rites was secondary to its original function as a device. astronomical or surveying.

Is Dixon Relics a construction tool?

On a more practical level, it should also be noted that the metal hook may have some connection to the metal latches fixed on the Gantenbrink door. Because this tool was found in the air-sealed shaft—perhaps initially at the base of the door before sliding down the shaft—it is reasonable to speculate that the tool had something to do with the secured pieces in the door.

However, the pegs are too far apart to accommodate both arms of the grappling hook, but one can’t help but wonder if the hook attached to its wooden pole was used for some purpose for positioning or locating left the door of Gantenbrink during the construction of the pyramid. This possible function of the tool was also mentioned by Bergdoll, who suggested that two similar poles with grappling hooks attached could have been used together to locate the blocks identified by Gantenbrink.

Bergdoll also identified other ancient Egyptian metal hook-like objects similar to those found by Dixon—for example, an object believed to be a ‘lock’ and located in the British Museum—but in as these comparable objects attest to Dixon’s antiquity. hooks, they add little to our current understanding of the functions of objects.

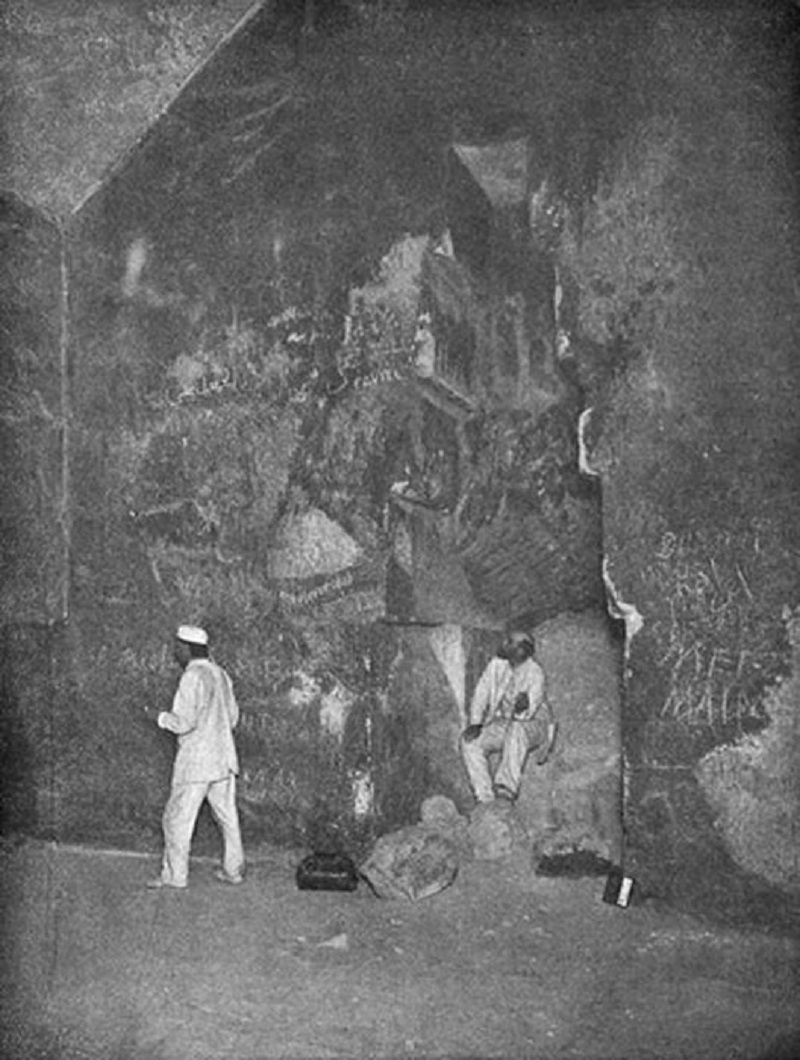

The Queen’s Chamber of the Great Pyramid where the Dixon relic was found. (Bakha~commonswiki / Public Domain )

Traditional building and construction rituals

Because the presence of materials in shafts is as unique as the shafts themselves in pyramid architecture, it was important to establish a precise precedent in Egyptian culture regarding the placement of artifacts. challenge. However, the ritual burial of special tools was not unprecedented in Egyptian construction practice.

The tradition of foundation deposits, dating from the earliest dynastic period, may shed some light when examining artifacts associated with sacred buildings, as Dr. Eiddon Edwards has noted in a 1993 Independent article when the Dixon site was rediscovered.

Founding ceremonies are used to dedicate and consecrate structures, especially sacred structures such as temples, and can incorporate anything from ritual purifying the ground to the rope pulling ceremony. Among these rituals was the tradition of burying special objects in the corners or shafts of buildings, a custom that spanned most of the ancient world, from early Mesopotamia to ancient Greece. grand. Egyptian deposits often included amulets, pottery, dinnerware, tablets and, notably, model tools – some were even ritually broken before burial.

Carpenter’s Proclamation from the Foundation’s Deposit – Temple of Hatshepsut. (Paros / Public Domain)

Adze Model 1479 –1458 BC. (Paros / Public Domain)

Contrary to their name, deposits were not always placed at the foundations of buildings in the ancient world. While Egyptian deposits were often placed underneath the building, there are a number of cases elsewhere in the ancient world where deposits were made above ground, within the structure itself, such as in Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian temples. However, it should be mentioned that the Egyptian foundation-building rituals themselves were often completed before construction took place. In essence, stringing the ropes, ‘breaking the ground’ (breaking ground) and spreading the soil with special plaster powder—as Rameses II is described to have done before building his temple to Amun—required construction to be imminent. happens, not begins. .

Burial of objects also needs to be buried before construction. For example, deposits found beneath the 12th Dynasty pyramid of Lisht, including the bones of a sacrificial bull, were placed at each of the pyramid’s four corners before being sealed with limestone blocks to become the corner blocks of the pyramid base. .

Indeed, even the modern equivalent of these ceremonies, the ‘groundbreaking’ ceremony used by modern builders, takes place before the start of major construction projects. However, due to their location within the pyramid’s structure, the Dixon monuments would require a foundation-laying ceremony to take place during construction or after construction to place them within the Queen’s Chamber shaft, where they were later discovered, this appeared to be a breach of regulations. Egyptian pre-construction traditions. If the relic is part of a so-called bedrock deposit, it is an atypical relic. The ritual breaking of tools, then (assuming that the cedar stick was actually broken intentionally) suggests a different kind of building tradition, one that recalls the idea of a The master craftsman, upon completing his work, would ceremonially break his tools to officially end his work.

Former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Dr. Zahi Hawass wrote in a 2003 article that the artifacts may actually have been placed in the final stages of construction, as it is not known for certain. whether the shafts in the Queen’s Chambers were completely sealed or actually guided. to an exit that would have allowed artifacts to be brought in from outside the pyramid.

Interestingly, Miller, who believes that the Dixon artifacts may be surveying tools belonging to the chief architect of the Great Pyramid, also suggests that the tools were placed inside the shaft to maintained the secrets of Egyptian architectural and astronomical knowledge. The broken tools and their possible location after construction would seem to add a measure of support to some of Miller’s ideas.

If true, then pyramidologist Piazzi Smyth was mistaken in his initial assessment, and the objects would not have belonged to “the rulers of profane Egypt,” as he wrote in 1880, but to the very minds that created the Great Pyramid. It is difficult to say whether the foundation rituals, as Egyptologists now understand them, had any connection to the Dixon objects, but they do shed light on Egyptian recognition about the religious importance of building tools in the ceremonial dedication of architectural works.

Illustrations of sketches made by John Dixon showing the Dixon monuments. (Harper’s Weekly / Public Domain)

Unanswered questions about the Dixon site

In addition to its original purpose, the Dixon relic also has important significance for researchers. The only organic artifact discovered to date inside the Great Pyramid (excluding the red ocher-cleaned cartouche and external mortar used in the 1984 dating studies and 1995, discussed in a 1999 Archeology article), the wooden bar has attracted particular attention from researchers. If the rod is located, it can be radiocarbon dated to provide an estimate of when the rod was made and placed inside the shaft.

For some researchers, this means dating the inside of the pyramid. Dr. Zahi Hawass, in the aforementioned 2003 article discussing the monuments, questioned the notion that dating the stick would provide a date for the construction of the pyramid, since it His point is that artifacts can be brought in at any time after construction.

However, the story continues. Gantenbrink’s research of the south plane shaft in the 1990s revealed what appeared to be other artifacts that had not been recovered, perhaps the remains of the ‘wreckage’ mentioned by Dixon. Interestingly, one of them is a wooden stick that John DeSalvo of the Giza Great Pyramid Research Association believes is the remains of a wooden stick left by Dixon in the channel.

As reported in a 2002 article, Robert Bauval traced the stick’s final location to the Marischal Museum in Aberdeen, Scotland, where Dixon’s colleague, Dr. Grant, allegedly delivered the artifacts . Today, the granite ball and hook are still on display at the British Museum, while the stick remains missing. For many, the case of the Dixon relics remains open, and their ongoing mystery remains a fascinating but little-known part of pyramid research.