Archaeologists have unearthed the world’s oldest fake eye

Shahr-i Sokhta (sometimes written as Shahr-e Sukhteh), meaning The Burnt City, is the name given to a substantial Bronze Age walled urban settlement in what is now southern Iran (fig. 1) [1]. The site has been excavated periodically since its rediscovery in 1900, and was granted UNESCO World Heritage status in 2014 [2]. Founded c.3200 BC and abandoned c.1800 BC, the settlement underwent four phases of construction, with three separate episodes of burning (hence the name). At its largest, it covered at least 100 hectares, the total site area spans some 151, including a 25 hectare cemetery with between 25,000 and 40,000 burials [1]. The abandonment of the settlement, along with several other contemporary sites, brought an end to urban occupation of the region for some 1500 years. Climate change, drought and the breakdown of trade networks are all posited as causes for this widespread settlement loss [3].

There is evidence from the site for trade connections with Mesopotamia, Central Asia, India and China, and ‘cultural packages’ that place Shahr-i Sokhta in the cultural area of both the contemporary Helmand and Jiroft cultures [3]. Since 1967, teams from Italy and Iran have been regularly excavating sections of the settlement, with new discoveries reported every few years, including the earliest known animation, and the first example of backgammon pieces [4].

Archaeologists have unearthed the world’s oldest fake eye. A ‘palace’ has been previously uncovered, as well as dedicated industrial neighborhoods, homes and storage rooms [3]. During the 2007-8 excavation season, the team investigating the Burnt City put trenches into a known cemetery and a craft area [5]. Within the funeral they uncovered 54 graves, containing 56 individuals and 270 grave goods [6]. In one area (Square MJN) only children and females were recovered, the absence of males suggests sex-based segregation. This area also contains some of the ‘richest’ graves, while another (Square NGL), on the edge of the known cemetery area, contains four children, two males and three of unknown sex, with a total of 35 grave goods, compared to 134 in the ‘rich’ area [6]. Again, there appears to be division of status/wealth, as well as sex, but seems not age. Several more areas of the cemetery were investigated, but unfortunately poor preservation limits the extent to which this theory can be proven – it may simply be the result of selective preservation.

The most dramatic burial from Square MJN was Grave 6705. This grave contains the skeleton of a young-middle adult woman, aged between 28 and 35 when she died. She was well preserved, and around 1.8m, exceptionally tall. Within her grave were 25 pottery vessels, a copper alloy mirror, 10 beads, made from lapiz, lazuli, or turquoise, and the organic remains of a leather bag and a mat basket [6]. Organics survived so well that it was possible to identify textile fragments on the bones, evidence that she was wrapped in a shroud [6]. The most striking and unique element of this burial, however, was found in her left eye socket. A 3 cm, hemispherical artefact made from bitumen and animal fat, the first known prosthetic eye in the archaeological record, dated between 2900 and 2800 BC (fig 2-4).

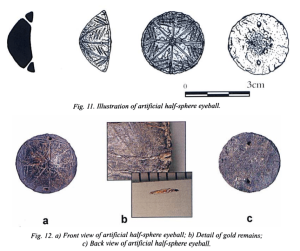

Archaeologists have unearthed the world’s oldest fake eye. The eye is black, with a central circular false cornea [6]. Radiating from this are eight regularly spaced lines, and incised decoration that forms diamond patterns. Gold wires under 0.5 mm thick were placed within these patterns (fig.4) [6]. Three small spots of white pigment on the eye surface hint that it may have been painted white over the whole surface, mimicking the sclera (white bit) of a real eye, with the gold wires interpreted as capillaries [5]. The eye had two very small holes, one on either side, probably for thread which kept their eye in place, like an eye-patch [6]. This object was not created for the burial. Microscopic abrasions in the socket both where the eye would sit, and also where the thread would have been, show that she wore the prosthesis regularly, and for some considerable time [6]. An abscess in her left orbital ridge has led investigators to believe that the prosthesis caused an infection in her eyelid due to long-term contact [6].

Investigators have also suggested it is an imitation sun – the lines representing sun rays. They posit that the creator, or the wearer, were basing the construction of the eye on a kind of emission theory – the idea that seeing is associated with light emanating from the eye [5]. The prosthesis would obviously not have been functional, so its existence provides an excellent insight into contemporary views of beauty, identity, status, and disability.

Variously described as a member of a royal family, a priestess, a wealthy woman and a soothsayer, it does seem likely that she may have held some unique status within the community. Her burial accompaniments are rich, her grave is large, and her eye is unlike anything else from the contemporary archaeological record. She was, it seems, not ostracized for her disability, her unusually large stature or her possibly non-local origin (though this is based solely on skull shape) [7]. She may have been seen as somewhat ‘other’ though – certainly a striking figure, and if the investigators are to be believed, perhaps she was thought to posses sight through the prosthetic.