Representing a national first, an ancient sarcophagus bearing the title “Emperor’s Protector” has been unearthed in western Turkey (ancient Anatolia). Furthermore, it’s also the first time the remains of an individual Imperial bodyguard have ever been found.

Leaving a Legacy

How will you be reminded in time? This question was of great concern in Roman times. Especially in the generally short lives of soldiers, politicians, and their bodyguards. Thus, the burial practices of ancient Roman elites between the 2nd and 4th centuries AD made heavy use of elaborate marble and limestone sarcophagi, with their life achievements and post death instructions carved in relief on the coffin’s exterior.

The Emperor’s Protector burial site was found between 2017 and 2019 in the province of Kocaeli, in western Turkey, while excavators were laying the foundation for a new building. Now, the Kocaeli Archeology and Ethnography Museum Directorate says the site has yielded “37 individual graves” including the magnificent sarcophagus carved with the Latin inscription “Emperor’s Protector,” according to Arkeonews. Furthermore, the emperor’s protector’s life story and immortal afterlife instructions were carved on the side of his coffin. According to a report on TRT, “this is a first for Anatolia.”

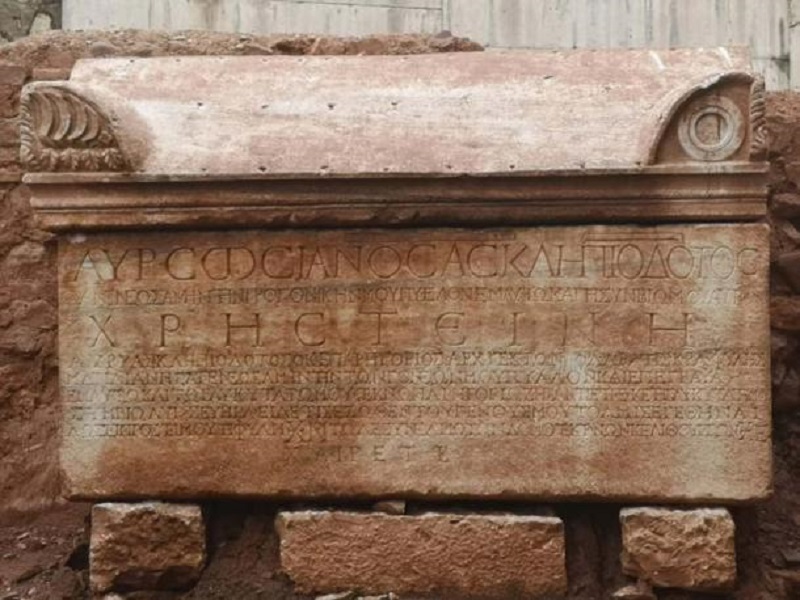

The side of Tziampo’s stone coffin inscribed in Latin with his legacy and hopes for the afterlife. (TRT)

The Life and Death of Tziampo: The Emperor’s Protector

Associate Professor Hüseyin Sami Öztürk from Marmara University said the sarcophagus belongs to a man named Tziampo, who was a personal bodyguard of Emperor Diocletian (who ruled or co-ruled the Roman Empire from 284 to 305 AD). Tziampo was very clear as to how he wanted to be remembered in history, and on the side of his stone tomb a Latin inscription reads:

“I lived 50 years. I do not allow anyone other than my son Severus or my wife to be buried in this tomb. I served in the military for 9 years as a cavalry, 11 years as an ordinary person, and 10 years as a protector. If anyone dares to bury another in this tomb, he will pay 20 follis to Fiscus and 10 to the city coffers.”

Emperor Diocletian: The Stabilizer of Rome Had a Green Thumb

The Praetorian Guards: To Serve and Protect the Roman Emperors… Most of the Time

Serkan Geduk, Director of Kocaeli Archeology and Ethnography Museum, said Tziampo was of Romanian origin before he joined the Roman army as a cavalryman. Trained to disrupt a line of enemy infantry, cavalrymen attack the flanks of opposing battlefield formations: segueing, arresting, and slaughtering retreating and fleeing enemy soldiers. After nine years of frontline chaos Tziampo was promoted to the rank of ordinarius (captain), and in his 11th year of service he was awarded the illustrious title of the Emperor’s Protector.

The Emperor’s Protector was a title earned by less than ten elite bodyguards serving in the Praetorian Guard. This stone relief shows the Praetorians with an eagle grasping a thunderbolt with its claws. (JÄNNICK Jérémy / Wikimedia Commons & Louvre-Lens)

A James Bond Level Imperial Protector

Reports about Tziampo are all quite dry and they fail to demonstrate that he was in reality a cross between Conan the Barbarian and James Bond. However, this highly-trained killer warrior was one of Emperor Diocletian’s private guards, and as such, he would have rubbed shoulders with the highest ranks of the Praetorian Guard. For three centuries this elite unit of the Imperial Roman army escorted high-ranking political officials, and they also served as a network of intelligence agents during the Roman Republic.

It was Diocletian, upon retiring on May 1, 305 AD, who reduced the size of his “Castra Praetoria” to only a minor garrison stationed in Rome. It will appear Tziampo, and his team did their jobs well, because according to LiveScience “20 percent of emperors were assassinated.” But not on Tziampo’s watch!

Speaking archaeologically, Tziampo is among a group of only eight elite bodyguards, as no more than seven other emperor’s protectors have been found so far. Geduk said the other seven bodyguards originated in “Italy, Croatia, Serbia, Algeria, and Arabia.”

However, Tziampo is special. Not only because he represents the first time a protector of the emperor has ever been found in Anatolia, but because his skeleton was intact and surrounded by sacred artifacts. Archaeologists unearthed a range of ritualistic grave goods around “two skeletons,” the other being Tziampo’s wife. This represents the first time any material remains have been found in the tomb of an imperial Roman bodyguard.

While we have only discussed the tomb of Tziampo herein, five other sarcophagi were also discovered at the site, of which four have Latin inscriptions. Together, the collected grave goods and human remains found at the Kocaeli site will fill in a lot of gaps in the story of Anatolia under Roman rule, both in life and in the afterlife.