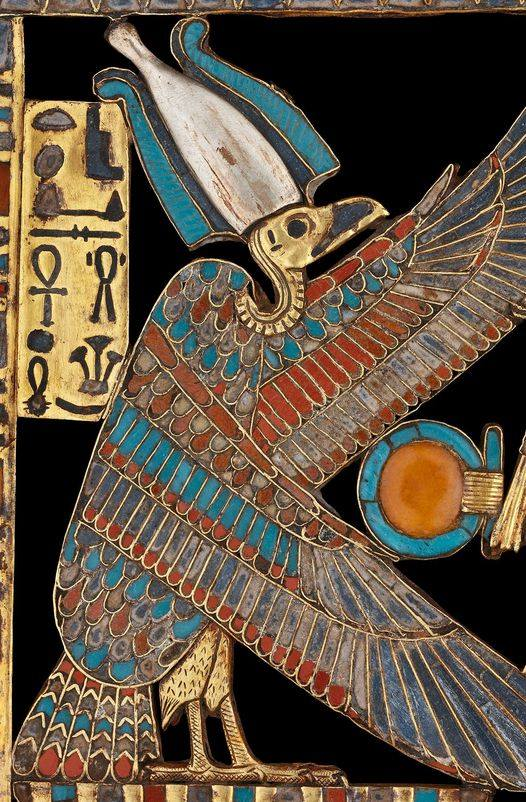

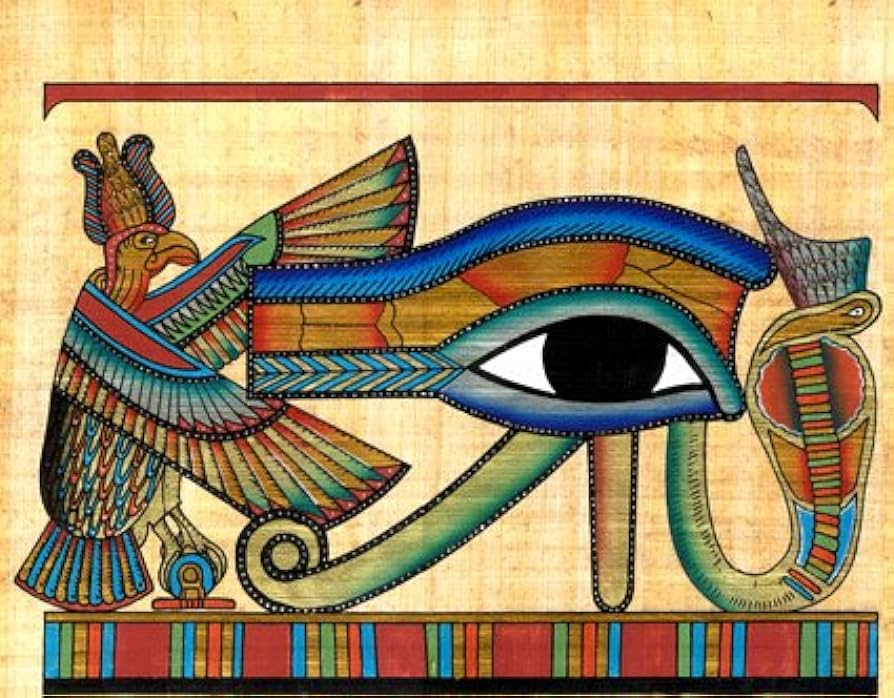

Detail of a shrine-shaped pectoral made of gold inlaid with silver, semi-precious stones, and multi-colored glass paste. It was found in the tomb of King Tutankhamun, who reigned circa 1336-1327 BCE during the 18th Dynasty.

We see what appears to be a depiction of Nekhbet―the patron deity of Upper Egypt―in the form of a vulture with extended wings around a shen ring (representing eternal protection). Interestingly, however, the inscriptions here name this deity as Isis. The goddess wears a white crown of silver with two plumes, reminding us of the Atef Crown.

“Gold and silver, the precious metals of Old World antiquity, appear in Egypt at least as early as the Predynastic Period, and remained in use thereafter for the manufacture of ritual and funerary objects and personal possessions. Gold has been particularly associated with ancient Egypt in the minds of the public and Egyptologists alike, even before the spectacular discoveries in the tomb of Tutankhamun in the 1920s. Our culture, like most others that have preceded it, pays more attention to gold than to silver, but certainly the relative scarcity of large or complex silver objects from ancient Egypt, particularly those dating before the Eighteenth Dynasty, has shaped our perceptions of the significance and value of silver to the Egyptians of ancient times.

Early sources of gold in Egypt and Nubia are well known from contemporary texts and from evidence of exploitation in antiquity. Gold was available from alluvial deposits in dry river beds in the desert, known as wadis, or mined from veins occurring in quartz formations. Many texts attest to royal expeditions to mine gold, while others mention the gold received as foreign tribute and booty and through trade.

By way of contrast, silver was not readily available in Egypt, and this is reflected in both the archaeological record and in ancient texts. Availability and value, however, did not have a consistent inverse relationship, and gold took precedence over silver in terms of economic value beginning in the Middle Kingdom, while silver was still the less common metal. The ancient Egyptians had no true coinage until the fourth century [BCE], and our understanding of the relative values of the two metals is based on the order in which they appear on offering lists in temples of pharaonic date.”

― Schorsch, Deborah, “Precious-Metal Polychromy in Egypt in the Time of Tutankhamun,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Volume 87, issue 1, December 2001, pp. 55-71.

This pectoral (JE 61946) is now in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt.