Cave paintings of Għar Ħasan

Hidden in the cliffs along Malta’s south coast, about 2km west of Marsaxlokk Bay, lies a cave system called Għar Ħasan. With its grand, stunning entrance overlooking the sea at a height of 70 meters (229.7 ft.), Għar Ħasan was once a tourist attraction. Today, the area around the cave entrance has been fenced off. Before this happened, one could walk along the footpath towards the edge of the cliff. Here a set of steps and a narrow stone path, with a rusty railing for safety, lead along the steep cliff face to the cave entrance.

Ghar Hasan Cave. (Coastal road)

At the entrance, Għar Ħasan is a tunnel that runs straight into the rock. For the first 20 meters (65.6 ft.) it is pleasantly spacious; Its large triangular entrance offers stunning views of the sea and allows enough light for one to find one’s way through the irregular cave bottom. Going straight forward, the cave becomes increasingly narrower and lower. At this time an iron gate blocked the way.

Side passages opened up from the main gallery, most of which soon dead-ended. But a larger branch turns to the right and winds through the rock in an easterly direction, parallel to the outer cliff face. A torch is needed here. After about 50 meters (164 ft.), it widens into a room with a door to the sea. From here, the narrow tunnel continues for another 70 meters (229.7 ft.), until ending in an artificial circular room with a stone bench around the walls. Here too, the door opens like a window allowing a beautiful view of the sea. According to legend, this is the room where a runaway Saracen slave named Ħasan lived a long time ago.

In this cave system, world-renowned expert on rock art, Professor Emmanuel Anati, discovered cave paintings during a visit to Malta in the late 1980s. They consist of shapes animals, handprints and hieroglyphs in red and black. Covered by a thin layer of minerals left by stalagmites that have dripped over time, these images are faint but still visible to the naked eye. They are recorded photographically at the time of discovery.

Examples of vermilion spiral cave paintings at the Hypogeum. (Damien Entwistle/ CC BY NC 2.0 )

Anati donated his manuscript with color photographs, dated 1989, to the library of the Archaeological Museum in Valletta. He wrote:

“Many of the images are unclear and partially covered by shells, so systematically detecting them is quite difficult. However, it can be established that the stylistic, associative, graphic and conceptual patterns reflect a class dating from the hunter period, before the Neolithic period, which has not been previously reported in Malta. Surprisingly, among the animal images were identified a number of figures that appear to represent elephants, an animal that is commonly believed to have become extinct in the archipelago at the end of the Stone Age. old, even before rising sea levels cut off the Maltese islands. from Sicily. The date of this geological period is not clearly established and there are many different hypotheses, although all scholars agree that this period occurred before 12,000 years ago. (Author’s translation)

In the 1990s, after these findings were announced, the paintings seemingly disappeared from the cave walls. Photographs taken during and immediately after their discovery may be the only reminder that they ever existed.

Hypogeum’s bull fresco

Another example of ancient Maltese cave art suffered the same fate as the rock paintings of Għar Ħasan. It involves a fresco of a bull inside the ancient underground temple at Ħal Saflieni called the Hypogeum. The fresco was discovered in the 1950s and photos of it were taken. It was also recorded and duly recorded by archaeologist David Trump in his 1971 book Malta: A Guide to Archeology.

Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum photo by Richard Ellis before 1910. ( Public Domain )

The painting was done using black manganese oxide, a substance commonly used in Paleolithic cave art. According to Mifsud, both the application of this paint and the design of the bull clearly indicate a pre-Neolithic date for this part of the Hypogeum. He recalls that in the late 1980s, UNESCO experts took paint samples and tests confirmed the Paleozoic date.

The fresco of the bull no longer exists today on the Hypogeum wall. A few years ago, an employee at the Hypogeum personally told me that one day in the 1990s, when the monument was closed for renovation, he was ordered to get a bucket of water and a broom to clean that part of the wall. The reason given to him for this order was that the wall had accumulated mold and needed to be washed. As far as I can verify, mention of the bull mural has disappeared from all publications except the 2010 reprint of David Trump’s aforementioned Guide from 1971. When asked during a group tour of the Hypogeum in 2008 why the bull fresco was not mentioned in his recent works, Trump replied: “It’s very faint.”

Hand ax found in Comino

A few years ago, I was introduced to Tony Lautier, a diver and tour boat owner in Gozitan, who wanted to show me some finds.

On the table in his garage are several objects displayed. They are all of stone, among them small pieces of black obsidian covered with a patina that shows their remarkable antiquity. There is also a larger, rougher and much lighter colored stone. It is wedge-shaped, slightly oval, tapering to one side. When Lautier held it up for me to see, his hand fit it perfectly. The stone appeared to be slightly shaped, such that his third and ring fingers were in shallow recesses carved along one of its long edges. Although these make the object fit perfectly in his hand, this feature alone would not prove anything. But the head of the farming tool was broken. It was clearly used as a tool, and the patina on its broken surface suggests this did not happen recently.

This object is made from hard Coralline limestone which occurs throughout the islands of Malta. It was the size and shape of a primitive hand ax like those made by Neanderthals. This implement was found along the water’s edge of the San Niklaw Bay beach in Comino, thus in a non-stratified context. However, the broken tip clearly shows that this primitive tool was once used as a hand ax or stone hammer.

The walls of Ggantija in Malta (upper part of photo) are made of rough coral limestone, in contrast to the interior architectural elements (lower part of photo) which are made of Globigerina limestone. Globigerina limestone is softer and easier to work with and smooth. This makes it suitable for interior finishes, such as the three-piece stone niches shown here. (Michael Gunther/ CC BY SA 4.0 )

Parallel channel on the seabed

In recent decades, Maltese experts from the diving community have made great efforts to investigate the seabed around the islands. Despite the skepticism they always endured, all these surveys were carried out at their own expense, out of pure love for their country’s history.

During one of these diving expeditions, Kurt and Shaun Arrigo, diving school owners from Sliema in Malta, while searching for underwater temple ruins, found some very interesting man-made features of other nature. in this process.

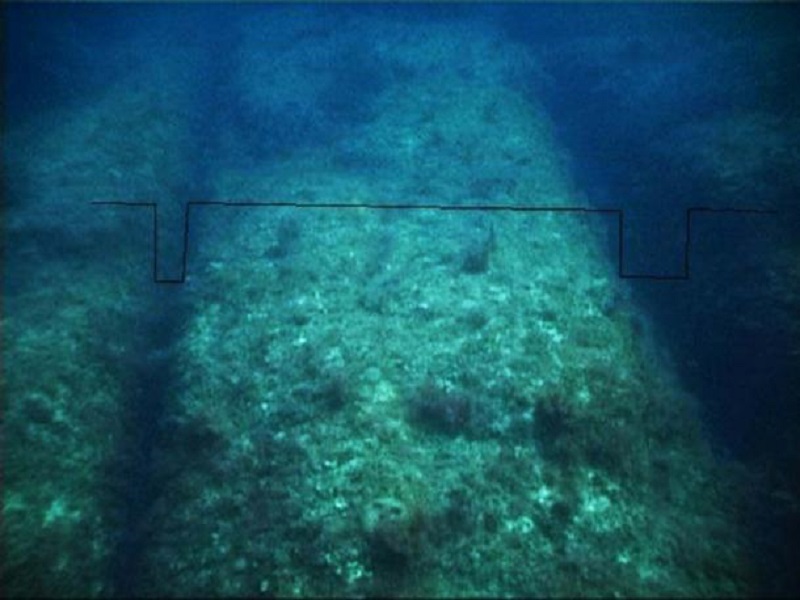

Off the northeast coast of Malta, in the area around the Gulf of St. George, large canals were discovered lying parallel to each other, as a clear indication that they must have been man-made. They were found 8 to 10 meters (26.2-32.8 ft.) below sea level, suggesting that they must have been created at least 8,000 years ago, which means they are at the latest. Neolithic period. Although they resemble the mysterious ‘carriage tracks’ that can be found across the mainland surface of Malta and Gozo, Shaun Arrigo has made it clear that they are much larger and deeper than the tracks on land immediately.

As far as can be determined at the time of writing, these underwater canals have not yet been formally studied.

Parallel canals are found in the Gulf of St. George. Credit: Shaun Arrigo

Monolith in the Sicilian Canal

Megalith builders were active in the central Mediterranean immediately after the end of the last Ice Age. This can be inferred from the recent discovery of a giant megalith, shaped by human hands, found at the bottom of a Sicilian canal. Recently found, the monolith is 12 meters (39.4 ft.) long and has a hole drilled through the thickness of the rock at one end. It lies on a flat plateau 40 meters (131.2 ft.) below sea level, 60 km (37.3 mi) south of the southwestern tip of Sicily. Whatever the reason it was placed there, the event must have occurred 11,000 years ago or more, during the early Neolithic period, when sea level was still below the platform on which it rested.