An interdisciplinary team of archaeologists and biologists from Oxford University recently completed a study of parasite infections in ancient Britain. Their exhaustive survey covers a period of over 4,000 years and concludes that people living in England have battled parasites throughout history, suffering from intestinal worm infections since the Bronze Age, which began around 2,500 BC.

The Effects of Intestinal Parasites Throughout History

In an article just published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, the study authors introduce the results of their innovative and revealing research project, which offers new and unique information about how people were affected by intestinal parasites during various historical eras.

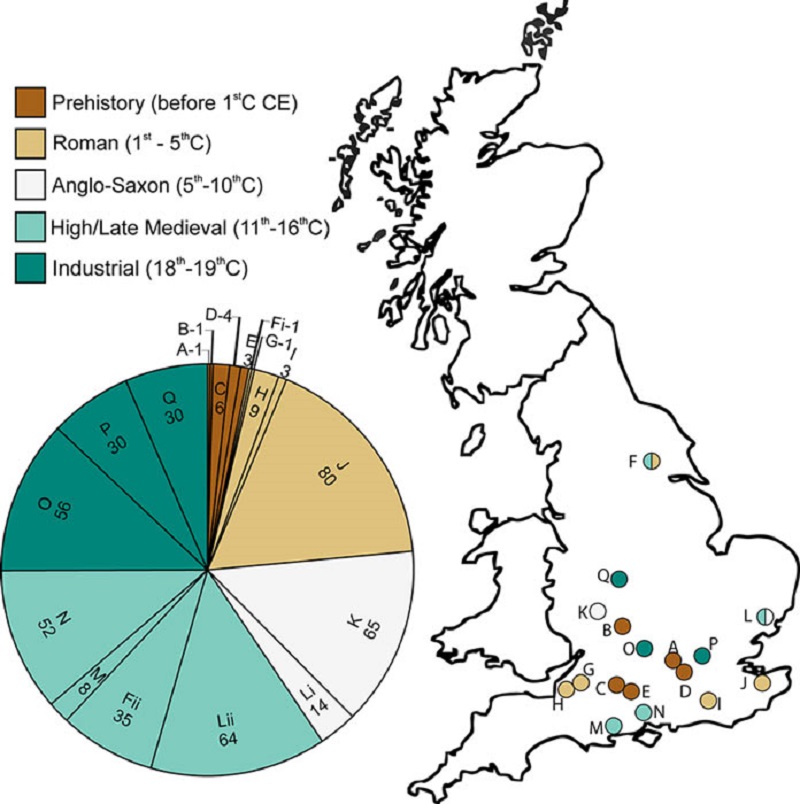

To obtain the data they sought, the Oxford scientists collected soil samples from inside the graves of 464 individuals who were buried at 17 mostly ancient archaeological sites across Britain. These sites were dated from the British Bronze Age to the near-modern Industrial Age, meaning they cover more than 4,000 years of British history.

The researchers then analyzed these samples looking for dormant parasitic worm eggs, knowing that if they found them it would mean the individuals buried in those graves had been infected by parasites at the times of their death.

Representational image of a human skeleton. The study has taken soil samples from below the pelvic areas of skeletons to analyze the remains of parasitic worms. (Mulderphoto / Adobe Stock)

Analyzing Parasites of the Long-December

The soil samples the scientists removed came from below the pelvic areas of the skeletons they unearthed. Parasitic worms would have been lodged in the intestines of the long-deceased individuals who carried them, and the remnants of worm eggs would have been deposited beneath the pelvis as the buried bodies decayed.

Using this clever approach to study the biology of people whose bodies no longer exist, the Oxford researchers were able to confirm that Bronze Age Britons had indeed suffered from parasitic infections, as had all the generations that came after. They discovered that individuals living during the Roman and Late Medieval periods were the most frequently infected, although people living in every historical era between 2,500 BC and the 19th century had to deal with parasitic worms to some degree.

In the graves of those who were buried during the Industrial years of the 19th century, there was a noticeable decline in the frequency of parasitic infections. Not coincidentally, this was when public health strategies were first implemented with the intention of improving public sanitation and personal hygiene. In the Victorian era in particular there was a so-called Sanitary Revolution that led to a sizeable decrease in parasitic infection rates all across Britain.

Improvements in sanitation in these later ages will have been linked to the installation of water- and sewage-treatment facilities in densely populated areas. People also stopped using human excrement obtained from cesspools, septic tanks, and outhouses as a form of fertilizer.

Pie chart showing number of samples, proportion of the sample set and the time period of each of the 17 sample sites in the study. (Ryan, H. et. al. / PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases)

How—and Why—Parasitic Infection Rates in Britain Changed Over Time

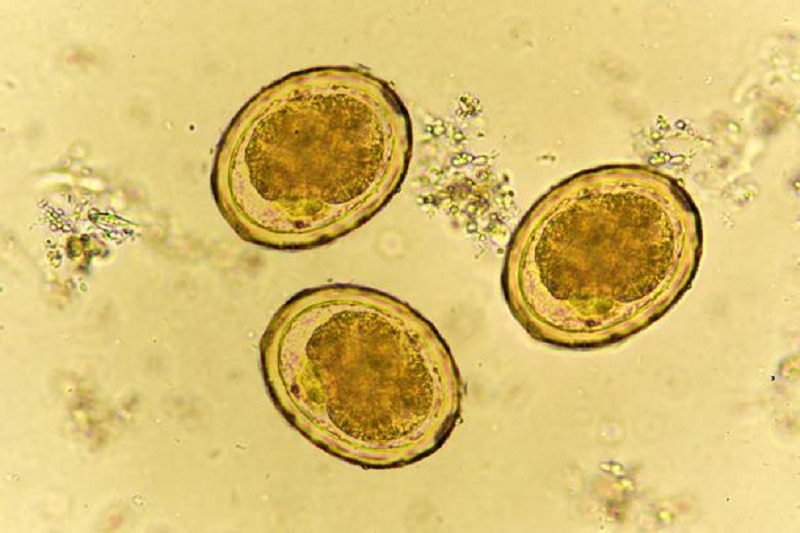

In their soil analysis, the Oxford researchers were looking for species of worms known as helminths. Some of the more common helminths are tapeworms, round worms, and whip worms, all of which are known to infect humans to this very day.

These parasites are usually picked up through contact with soil or water that has been contaminated with raw, drained sewage. In the case of tapeworms, parasites can also be contracted by eating undercooked or raw meat or fish. Helminths lodge themselves in the intestinal systems of their victims, where they can absorb partially digested nutrients before they can be passed on to their host’s body. The result is that people with parasite infections become weaker and more and more hazardous to all types of diseases.

While evidence of parasitic infection was found at prehistoric burial sites, parasites that preyed on humans were not particularly common at that time. It would seem the unsanitary practices that make people vulnerable to parasites were not widely practiced yet, although the parasites were able to gain at least a small foothold in Bronze Age populations.

Parasitic infections in Britain first soared during the Roman period, specifically between the second and fourth centuries AD. Infection rates were even higher during the High or Late Medieval period, or between the 11th and 16th centuries. Increased population densities combined with the unsafe or unregulated of human waste likely accounted for these health issues, as parasitic animals thrive in environments where sanitation and hygiene are neglected or ignored.

Intestinal parasite, Ascaris, under a microscope. (jarun011 / Adobe Stock)

Expanding the Search for Ancient Public Health Data

“Defining the patterns of infection with intestinal worms can help us to understand the health, diet and habits of past populations,” study co-authors Hannah Ryan and Patrik Flammer, from the Oxford archeology and biology departments respectively, said in an Oxford Press release . “More than that, defining the factors that led to changes in infection levels (without modern drugs) can provide support for approaches to control these infections in modern populations.”

Why the Romans Were Not Quite As Clean As You Might Have Thought

2,000-Year-Old Feces from the Silk Road Reveal Spread of Infectious Diseases

Ryan, Flammer, and the other members of the Oxford research team, were interested in studying how the incidence of parasitic infections in Britain changed over time. With such information it is possible to analyze how infection rates may have been impacted by the evolution of hygiene and sanitation practices. Scientific knowledge about the importance of cleanliness and sanitation has advanced by leaps and bounds since the Middle Ages, and through historical studies of this type it is possible to see how this increase in understanding was linked to better public health.

The Oxford scientists were thrilled with their results, which revealed quite a bit of information about parasitic infections in England over more than four millennia. They plan to use the same methodology to study other types of infection and disease that were experienced in ancient times, as they expand their search for data that could be valuable to public health officials all over the world.