Major collectors were established in the Great Pyramid and the muons flowing through the structure were measured in the hope of identifying any hidden chambers. The idea of a beautiful internal passage through the structure being revealed has excited millions of archeology lovers. Then the results came.

While a large void was discovered above the Grand Gallery, no internal ramp was discovered. Nada. This news of deflation was given by Bob Brier himself, the expert who first supported this theory: “these data show that the ramp is not there. I think we lost.” So if there is no ramp inside the Great Pyramid, how was it actually built? How were the rocks lifted hundreds of feet into the sky, beyond the ramp?

New research looking at the density of particles called muons has found an empty space (shown in this illustration) more than 98 feet (30 meters) long just above the Great Pyramid’s Grand Gallery , but no ramp was found inside the pyramid. (Pyramid scanning mission)

Combination of ramp and leverage

Any theory based on ramps, whether internal or external, runs into problems near the top of the pyramid. Lehner and Hawass admit that: “the fact that the four sides of the pyramid are so narrow that they are closed at the top means that the builders ran out of room for ramps.” (Lehner 2017; 418), and that: “it is likely that leverage was the only means of lifting the blocks of the highest courts, near the top, once the builders had brought them as high as possible on the gradient.” (Lehner, 2017; 417).

Other archaeologists have proposed a combination of ramps and levers, including Martin Isler in Pyramid Buildings I & II (1985 & 1987).

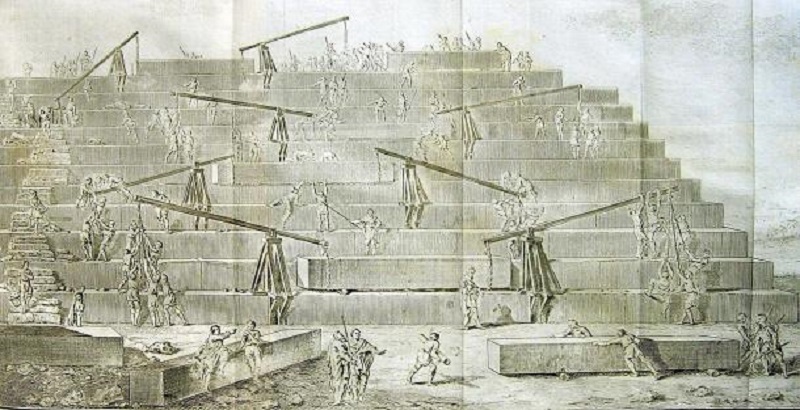

The idea of ancient Egyptians using technologies other than ramps was first proposed by Herodotus in 425 BC. He describes the construction of the Great Pyramid as follows: “This pyramid was built in steps which some call ‘rows’ and others ‘bases’: and when they did it this way For the first time, they lifted the remaining stones using machinery. short wooden logs, first raise them from the ground to the first level of the ladder, and when the stone reaches this level, it is placed on another machine standing on the first level, and from there it is pulled to second floor. on another machine.” (History 2. 125).

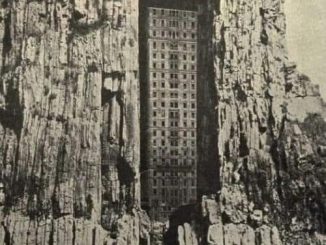

“Construction of the Great Pyramid according to Herodotus”, lithograph depicting many of the so-called ‘Herodian Machines’ operating on the Great Pyramid (Antoine- Yves Goguet (1820) / Public domain).

This description is reminiscent of a ‘liftjack’ tool, which uses levers and small shims or wedges to gradually lift a large block in many small steps. This was first proposed by Petrie in 1883: “for ordinary blocks, each weighing several tons, it will be practicable to use the method of placing them on two piles of wooden boards and moving them up alternately to one side and the other by crossbeams under the block, thus raising the piles and raising the stones in turn.”

A number of other scholars have also noted this theory, including Isler, who actually tested the theory on the 1991 Pyramid construction project filmed for NOVA. He discovered this was more difficult and took longer than he had anticipated, but that was mainly due to his inexperience and the instability of the wooden cradle.

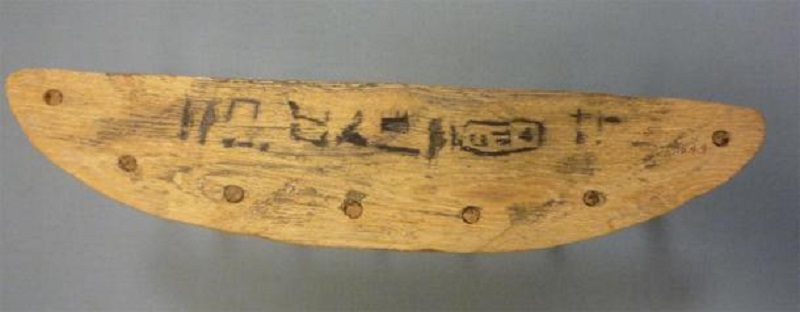

Supporting this method may be the mysterious round wooden objects known colloquially as “Petrie rockers”. Found by the famous Egyptologist at Thebes, he proposed that these semicircular wooden devices could be used to help lift heavy blocks by allowing them to tilt back and forth more easily (” push them alternately to one side and the other”), allowing successive planks to be inserted on either side and lifting the block up.

Others like Paul Hai imagine the Egyptians actually “rolled” the large blocks by tying a Petrie crane to each side of the block, creating a cylinder. Again, there is no evidence for this, and any wooden seesaws have never been found near the pyramids.

A wooden model “rocker” device found by Flinders Petrie at Thebes, from the New Kingdom, ~1450 BC. (Metropolitan Museum of Art / CC0 )

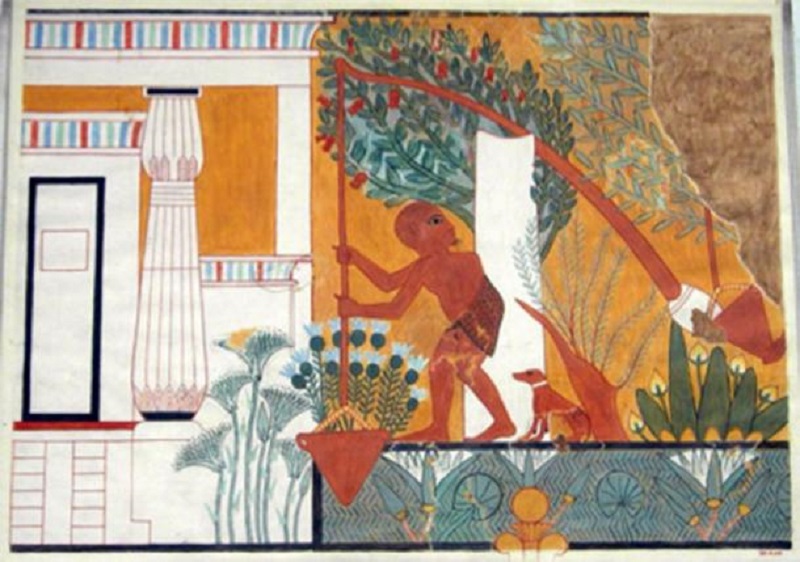

Alternatively, the Egyptians may have used a counterbalanced lever mechanism, similar to the shaduf, which has been used for millennia to raise water from the Nile. The machines described by Herodotus may have included wooden bars with counterweights, used to seesaw the blocks along each path.

Tomb painting of an ancient Egyptian gardener using shaduf (Tomb of the Royal Sculptor Ipuy, Deir el-Medina, 19th Dynasty, 1279-1213 BC). Shaduf is based on counterbalanced lever principles similar to the so-called “Heroduf Machine” imagined by Goguet and other artists. (Metropolitan Museum of Art / CC0 )

Did the Egyptians use scaffolding?

Other researchers such as Peter Hodges, Julian Kable, Louis Croon and Robert Scott Hussey-Pailos all made improvements on these designs, reducing Isler’s original lift time of more than an hour to just a few minutes. Whether the Egyptians used the seesaw lever method or the counterweight lever method, they would have needed some degree of wooden scaffolding.

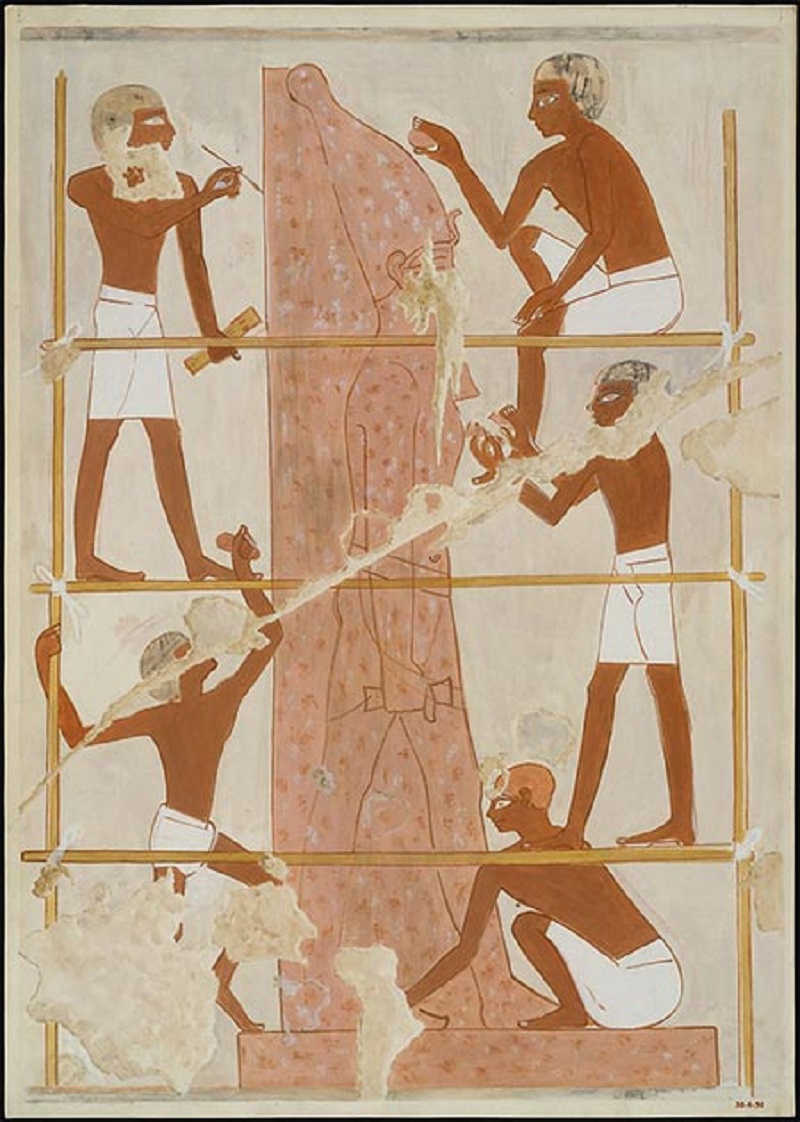

We have no surviving paintings or materials of any of these proposed lifting devices, but we do have evidence that the Egyptians were familiar with wooden scaffolding. In a painting from the tomb of Vizier Rekhmire in Thebes (~1450 BC), we can see several workers standing (and even sitting) on scaffolding while they polish and paint a statue big.

Depiction of wooden scaffolding from the Tomb of Vizier Rekhmire, ~1450 BC. (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Nina De Garis Davies/Public domain)

An earlier scene from the Khaemhesit tomb of Fifth Dynasty Saqqara shows a vertical wooden ladder with workers sitting along it, and surprisingly, there are wheels and an axle at the base of the ladder! This is the only known description of wheels from the Old Kingdom, and the Egyptians did not use them to move heavy pyramid blocks: the wheels would have sunk into the ground, and the material was not sturdy enough. for shafts.

Many researchers claim that scaffolding was used to help build the pyramids, as far back as Somers Clarke and R. Engelbach in their classic Architecture and Construction of Ancient Egypt (1930). Hawass, Lehner and Isler also voiced limited support for this idea, along with James Frederick Edwards in their article Building the Great Pyramid: Possible Construction Methods at Giza (2003). He specifically noted that masons could use scaffolding to lay smooth white Tura facing stones, often thought of as the final stage of the construction process. Perhaps the strongest proponent of the wooden scaffolding idea is Welsh structural engineer Peter James, who was called upon to save the Step Pyramid after it was damaged in the 1992 earthquake.

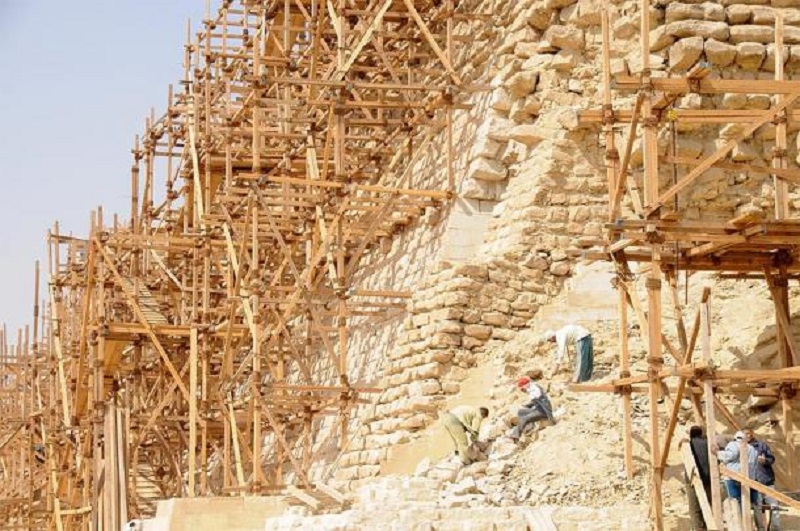

As detailed in the 2018 book Saving the Pyramids, James and his team worked deep beneath the Step Pyramid in Djoser’s burial site, using large airbags combined with wooden scaffolding for support. the ceiling is sagging. They carefully drilled narrow holes into the superstructure, inserted steel bars and cemented them in place, ultimately protecting the 4,700-year-old building – the world’s oldest stone building – from damage. fall.

Modern wooden scaffolding set up around Djoser’s Step Pyramid at Saqqara (David Broad / CC BY 3.0)

However, it was the abundant wooden scaffolding erected around the Step Pyramid to restore its crumbling facade that gave James the idea for its construction. He thinks similar scaffolding may have been used in the past, consisting of pieces of wood tied together: “In recent restoration work on the pyramids, traditional wood tied together has used as scaffolding, which proves that it is clearly possible to use scaffolding to build them in the first place.”

“We have people, we need wood”

Most scholars dispute the view that scaffolding serves any basic construction role, only taking on a minor function, such as decorating the stone cladding or laying the upper layers of bricks. together. This remains an unpopular idea for one simple reason: most Egyptologists believe that the ancient Egyptians, with their arid and relatively treeless environment, had limited access to wood. limit.

However, some scholars have demonstrated that Old Kingdom Egypt, around 2550 BC, would have had more vegetation than it does today. Researchers have demonstrated that a major climate change accompanied or perhaps caused the end of Egypt’s Old Kingdom around 4,200 years ago. For example, Jean-Daniel Stanley and his colleagues, using strontium isotopes and petrographic data, showed in their 2003 study that the water level of the Nile and thus the number of trees had plummeted during period from 2200-2000 BC.

As DM Dixon stated in his article Wood in Ancient Egypt (1974), “in ancient times, Egypt possessed and still possesses a number of trees capable of providing wood”. These include the date palm, acacia, tamarind, Persea, willow, sidder, moringa and sycamore. These trees were used to build boats, furniture, giant temple doors, coffins, bows and ramps, as described in Papyrus Anastasi I: “A ramp must be built … consisting of 120 compartments full of reeds and beams.”

Left: Acacia tree, similar to those found in Egypt and the Levant during the time of Khufu, Negev Desert of Israel. (Mark A. Wilson / Public Domain). Right: avenue of acacia trees leading toward the pyramids in 19th-century Cairo (William Henry Jackson (1894) / Public Domain)

Archaeological evidence of wood within ancient ramps has been found at Lahoun, Lisht and Deir el-Bahri. We also know that Egypt imported huge blocks of Cilician cedar and fir from Lebanon, this is confirmed by the discovery in 1954 of two damaged Khufu funerary boats buried beside next to his pyramid.

Al Arzz above Bsharri (God’s Cedar Forest), Lebanon. (BlingBling10 / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Made from giant cedar slats, they were tied together with rope and would seal by swelling in water. We know from the inscription on the Palermo Stone that Pharaoh Sneferu, Khufu’s father, sent an expedition of forty ships to Lebanon to collect the precious cedar beams: “Bringing forty ships loaded [with] cedar… Build a ship [with] cedar, one ship, 100 cubits [long].” 100 cubits is roughly equivalent to 50 meters (164 ft), even longer than Khufu’s boat at 43.6 m (143 ft).

Khufu’s beautiful boat, Sun Boat Museum, Giza. (David Berkowitz / CC BY 2.0 )

We can still see the massive 15m high cedar beams that Sneferu’s engineers inserted between the walls of the Bent Pyramid burial chamber to keep it from collapsing. He could easily have used similar beams to construct wooden scaffolding for the construction of his two pyramids at Dashur (and the earlier work at Meidum).

Ancient wooden beams remain inside the Bent Pyramid of Sneferu in Dashur. (Ivrienen / CC BY 3.0 )

Secrets of building pyramids

An interesting feature of the solar boats is that their beams are held entirely by hemp rope, which is also stored next to the boat. With cedar beams and strong ropes, the Egyptians certainly could have built a sturdy scaffold capable of supporting large blocks of stone and many workers.

I believe that the secret to building the pyramids, aside from the ramps, is actually very simple: a relatively narrow piece of wooden scaffolding, lashed together with ropes and securely anchored at the base . This would create large external mudbrick ramps, unnecessary internal stone ramps and the need to decorate the stone from above. The entire structure may have been finished in levels, with the outer layer of stone ground before starting the next layer (or even in the quarry when it was first removed, when it was softer and easier to touch). more severe, as Bob Brier noted).

I believe the work crews would use a combination of levers, seesaws, and wedges to lift the blocks up through the scaffolding to the active building surface, where other crews would take over. The scaffolding itself would have had dedicated teams of carpenters building it as the pyramid rose. Each level of scaffolding will have separate teams, while the teams operating on the pyramid will likely be divided again.

Most work crews will focus on internal fill and less precise internal masonry, some will focus on core blocks and mortar, while the most skilled will be stationed around external to set and perfect high and precise angles. Polished Tura limestone shell block. So I imagine a kind of assembly line process, from the quarry to the pyramid, with the teams staying at their positions and the rocks moving between them.

There is no good reason why the Egyptians could not have built a narrow section of scaffolding on the south side of the Great Pyramid to support all the blocks needed for its construction. It can then be removed very quickly and reused at subsequent pyramid projects or used as an alternative for solar boats, coffins, etc. Reusing wood was common in Egypt, as Pearce Paul Creasman demonstrates in his article: Ship Timber and Wood Reuse in Ancient Egypt (2013).

Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt. ( sculpies / Adobe stock)

The pyramids were built using technology available since the Old Kingdom: ramps, bronze chisels, stone crushers, levers, ropes, columns, plumb bobs, cubit bars, mallets, adzes, wedges and squares . I believe that, to these primitive but capable tools, we can add wooden scaffolding, the final missing piece to their construction puzzle.

However, it is not just this technology that has helped realize these huge construction projects. It was the organization and hierarchy of workers, overseers, priests, and scribes that helped make these grand national dreams a reality. It was the skillful coordination of this hard-working society, all based on the priests’ careful measurements of the seasons, the sky and the Nile, that eventually built the pyramids . It was a nationwide effort, one of the greatest in our history, to serve the kings and the gods and maintain balance in the land, so that their names and works would lasts forever.

Final note

Interestingly, Welsh architect and pyramid rescuer Peter James disputes the idea that the Egyptians used poles and ropes to raise their slopes at the sites. pyramid point, as suggested by the new ramp discovery at Hatnub. In a personal email communication, he discussed some of the flaws he identified with this model:

“The question of the size and diameter of the ropes needed to pull the heavy blocks was also an issue as was their strength on the edges of the cube. The method of attaching ropes to the blocks to avoid twisting the blocks as they are lifted is also an issue.

How can you ensure that the two groups of workers pulling the blocks can create equal tension on the rope to control the elevator and not cause twisting and movement of the blocks, especially when they are above the temporarily constructed steps? This would be a very dangerous operation.

The same goes for temporary wooden columns which may be suitable for permanent placement in quarries but will be susceptible to shifting under load on unconsolidated foundations and will again make it difficult to control the block; Additionally, the leading edge of the block will dig into the soil and any force used to move it will cause the block to move through the soil and prevent further movement.”

Jonathon Perrin is the author of Moses Restored: The Oldest Religious Secret Never Told, available in print or as an e-book from Amazon.com.