Krapina, a famous Neandertal site in northwestern Croatia, was excavated under the direction of Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger between 1899-1905. Based on fauna and geology, he suggested that the site dates back to the last ice age and that it now dates to 130,000 years ago. Gorjanović-Kramberger was a man far ahead of his time. The site was excavated stratigraphically and many human remains, animal bones and tools were labeled according to the level where they were found.

He tested the antiquity of Neandertal remains by comparing their chemical characteristics with the bones of extinct animals, being the first to use X-rays to analyze fossils, recorded by evidence for cannibalism and the saving of large amounts of material from the site. This was fortunate because the original sandstone shelter and the sediments within it no longer exist. Gorjanović-Kramberger published widely on the site and in 1906 published a long descriptive monograph, mainly on human fossils. He also allowed scholars to study the documents and as of 2006 there were over 3000 references to Krapina documents. One might think there is little to say about the website, but new ideas, new technology and new people add a lot.

In 1986, I began my work at the Croatian Museum of Natural History by recording toothpick grooves on countless isolated teeth. This is the result of continuously probing the interdental spaces, eventually leaving a groove at the crown/root junction. I worked with Mary Doria Russell, then a paleoanthropologist, but now a famous science fiction and historical fiction writer (e.g. , The Sparrow; A Thread of Grace ). Following the study of toothpick grooves is the study of scratches on the labial surfaces of incisors and canines. When they occur with a high enough frequency, they indicate whether the person is right- or left-handed. This work was carried out with Carles Lalueza Fox, currently one of the leading researchers in ancient DNA and proteins. It was wonderful working with these two and I have many fond memories of our time together. My later work involved describing the forehead cuts of the most famous Neandertal specimen from this site, Krapina 3, together with my friend Jkov Radovčić, who was then the curator of the collector and a number of other colleagues. Milford Wolpoff, my advisor from Michigan, found the forehead fragment in the collection and placed it on Krapina 3, some seventy years after it was found as an isolated bone fragment.

The marks appear to be related to some type of ritual as they do not match patterns seen in cannibalism, secondary burial preparation, animal trampling or damage measurement.

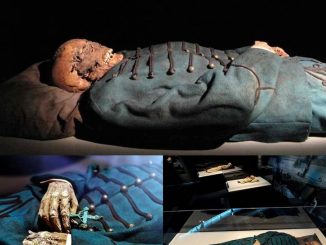

I have known Jkov and his family for over 40 years. When I was making toothpick paper, we often picked up his daughter, Davorka, from the kindergarten near the museum. We dumped her in the garden near a bar and she played while we smoked and drank beer and talked about Neandertals and solving the world’s problems. I remember her as a really cute kid. In 2013, she was no longer a child, and with a Michigan PhD from Wolpoff, she took over as curator from her father. She did a complete inventory of the Krapina literature and in 2014 emailed me that she had found eight eagle talons with cuts on some of them. Discovered together on the top floor at the site, they appear to be part of a necklace, bracelet or rattle. The claws had been studied before, starting in 1912, so I was a little skeptical.

When I arrived in Zagreb and saw the set of eight claws plus the phalanx, I was stunned – the cuts were so obvious. How could they have been missed for so long? Along with the notches, there were polished areas along the edges of many of the claws, some blackened areas from compaction in a few, notches on some of the edges of the toenails, and some clearly pigmented areas. In a cut, sealed by a layer of silicate, is a wavy fiber. Found on Talon 386.1, this is really interesting but also raises the conundrum of how to analyze the fiber without destroying it.

After various attempts, Davorka found Giovanni Birarda and Lisa Vaccari at the Synchrotron Infrared Source for Spectroscopy and Imaging – SISSI, Elettra – Sincrotrone Trieste, Italy. They were experts in infrared forensic analysis and after many long investigative sessions, Giovanni determined that the fiber was animal, not plant. Because of the comparative scale’s young age, he was unable to identify the specific animal. This is a different type of fiber than described last week in Scientific Reports by Hardy et al. from Abri du Maras in France. Theirs is twisted rope derived from coniferous trees, ours is from animals. The type of animal was not specifically identified, but surely some future worker with new techniques will more specifically identify the type of fiber and provide more information about it.

In addition to fibers, Giovanni and Lisa also analyzed some color stains on Talon 386.1. These are orange and black colors found in various areas of the claws. First are the dark spots. We think they are manganese dioxide, a common pigment used elsewhere by Neandertals. However, their infrared reflections suggest they are carbonaceous, possibly from the hearths Gorjanović-Kramberger recorded on the top floor at Krapina. It is unclear whether the black marks were accidental or intentional, but the claws showed no signs of being burned and black marks appeared in many other places of 386.1’s claws. It’s also present on most of the other claws, and none of them show signs of burning, so we think it’s likely that the carbon was intentionally applied. The orange stain was another matter—Giovanni identified it as a mixture of red and yellow ocher. These ochers do not occur naturally in cave deposits and must have been collected elsewhere and deliberately applied to the claws by Neandertals. It is also possible that the red and yellow pigments were transferred from other elements of the ornament, but they are clearly of human origin and not natural colors from cave sediments. There are other cases of Neandertals using red ocher, so this adds to the growing body of data on sophisticated Neandertal behavior, which many mistakenly believe is unique to modern humans. so them.

This would not have been possible without the collecting skills of Dragutin Gorjanović-Kramberger more than 100 years ago, without Davorka Radovčić who recognized the cut marks on the claws, or without infrared forensic work by Giovanni Birarda and Lisa Vaccari. It was a chance encounter that happened over a century ago. I have been fortunate to participate in this and my other research at Krapina and to work with these scholars, young and old. I look forward to new developments—there will be many.