An old English proverb says “necessity is the mother of invention”. At La Gomera in Spain’s Canary Islands, residents developed a need to communicate with each other about the island’s natural landscape of deep valleys and steep ravines. The result of this need was the invention of a language known as Silbo Gomero or el silbo, which means ‘Gomeran Whistle’ and ‘the whistle’ respectively.

Before the Spanish conquest of the Canary Islands in the 15th century, La Gomero was inhabited by a people known as the Guanches. Silbo Gomero is a whistled form of the Guanche language and is believed to have been invented by the indigenous people of the Canary Islands.

However, by the 17th century, the Guanche language had disappeared and little is known about it other than a few words recorded in travellers’ diaries and a few other words incorporated into the Western form. Spanish is spoken on the islands.

It is thought that the Guanche language had a simple phonetic system that allowed it to be adapted into a whistled language.

The narrow valleys of La Gomera. Wikimedia Commons

After the colonization of the Canary Islands, the islanders began to use Spanish as their spoken language. Out of practicality, like their Guanche-speaking ancestors before them, the people of La Gomera began translating Spanish into a whistling language. In the whistling language of La Gomera, each vowel or consonant is replaced by a whistling sound – two separate whistles replace the five Spanish vowels and four whistles replace the consonants. Based on the pitch changes and whether they are intermittent or continuous, sirens can be distinguished and any message can be conveyed from one user to another.

The whistling sound can be heard in the following short documentary:

In the past, whistling was passed down through direct contact between teacher and student, and often within the family. This has ensured its survival over the centuries.

Between the 1930s and 1950s, whistling was a means of protest against the government. Some older generations recall that during those decades, the Guardia Civil often picked up locals by truck and drove them to places on the island where fires had broken out to help extinguish the flames. This forced firefighting was not welcomed by the islanders (incidentally they were not paid for their hard work, although the council and mayor received money to pay them), and so they will warn each other using whistling language. Since the Guardia Civil do not understand the whistling language, they are often unable to find the locals because they hide when the Guardia arrives in their village.

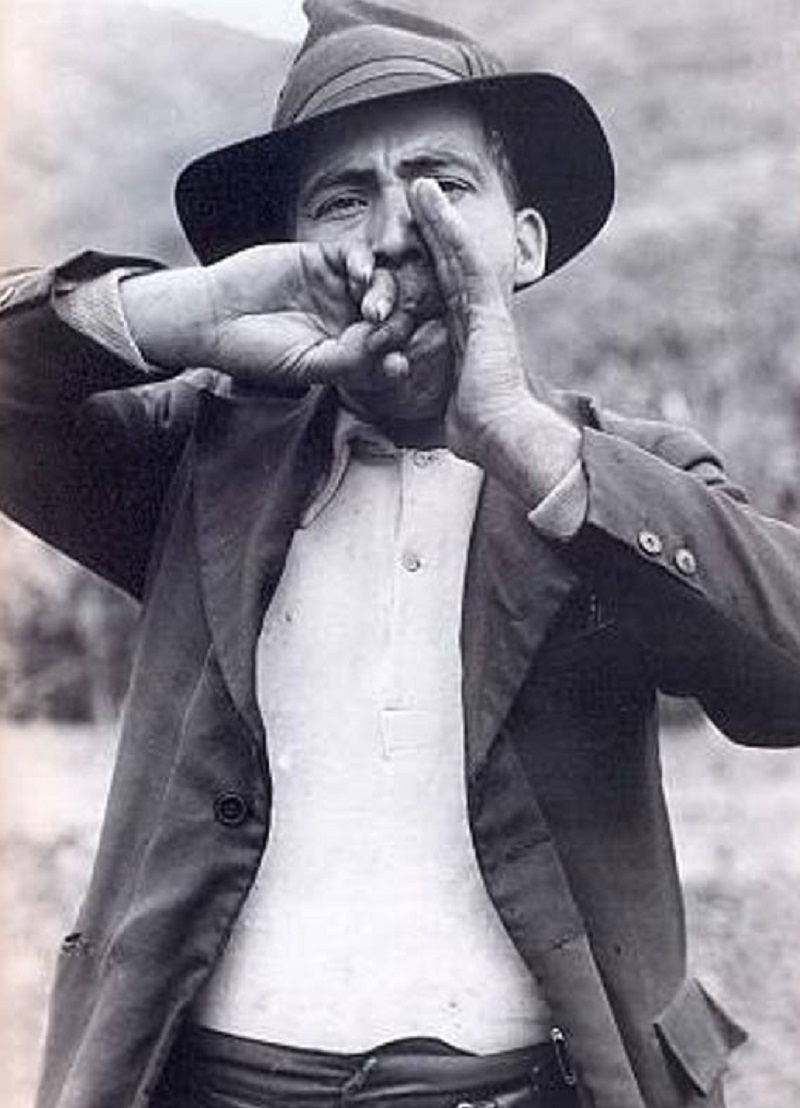

Man whistles in Silbo Gomero language. Service provider: Gouvernement des Canaries

However, by the 1950s, economic difficulties forced many locals in La Gomera to emigrate from their homeland to neighboring Tenerife and even Venezuela. As a result, the whistling sound begins to gradually decrease. La Gomera’s growing road network and the subsequent invention of the mobile phone further reduced the island’s residents’ need to use the whistling language.

By the end of the 20th century, there were so few whistling speakers that it was almost extinct. Fortunately, in 1999, Silbo Gomero was introduced as a compulsory subject in high schools across the island. In addition, the Canary Islands Ministry of Education spends about 100,000 euros ($106,000) per year on Silbo Gomero projects to maintain the language. As a result, the whistling language is being revived and around 3,000 students are now learning the language in their schools.

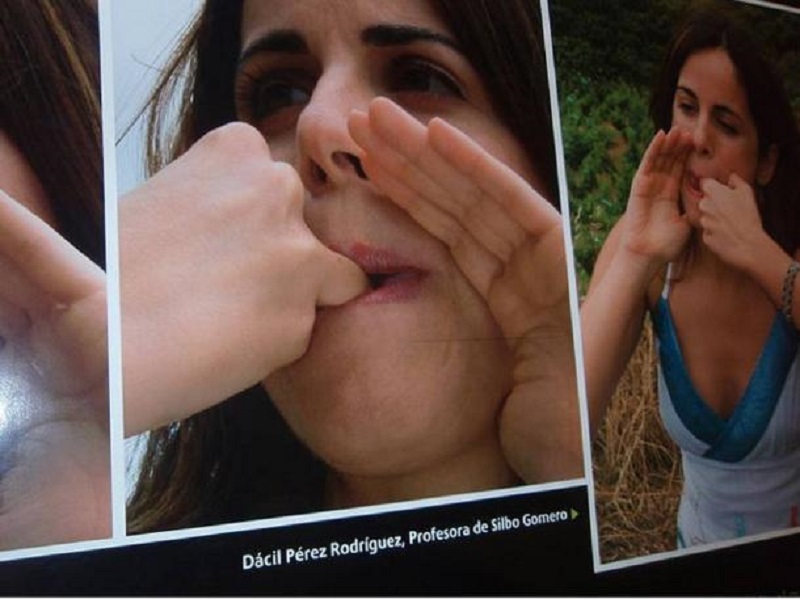

The photos depict modern uses of the ancient whistling language Silbo Gomero. Tino Prieto/Flickr

In 2009, the whistling language was inscribed on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, thus bringing international recognition to this unique heritage of the islanders of La Gomera.