Occasionally, objects of interest that come across my desk have certain characteristics that place them beyond our understanding. The mysterious Newton Stone is one such artifact, not only because this ancient monolith is inscribed with a message inscribed in a mysterious and currently unsolved language, but also because the writing can be explained using at least five ancient alphabets.

Discover Newton’s stone

Discovered in 1804 while George Hamilton-Gordon, Earl of Aberdeen, was building a road near Pitmachie Farm in Aberdeenshire, Scottish antiquities collector Alexander Gordon later moved the mysterious megalith to the garden of Newton House, in the Parish of Culsamond about a mile to the north. of Pitmachie Farm. According to Aberdeenshire Council of Newton House, the Newton Stone is described as:

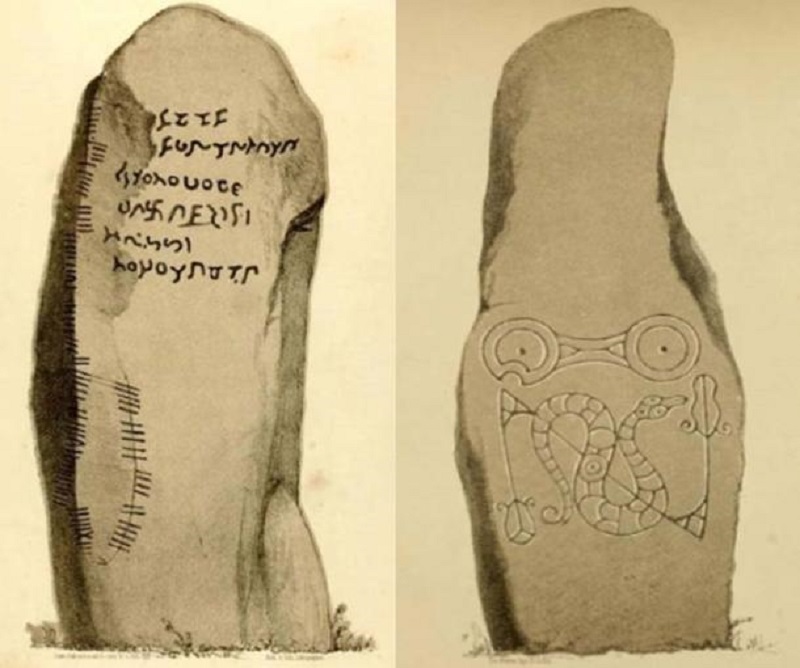

“made of green gneiss and about 2.03 meters high. It has 6 horizontal lines engraved at the top, believed to be outdated Roman writing, the meaning of which is unknown. To the left of this, below the stone, is the Ogham inscription. It contains a personal name (Ethernan) and additional material that is incomplete or not entirely legible. A ‘pea’ shape was observed engraved on the underside of this stone, which was identified as possibly a Pictish mirror symbol.”

The Newton stone and accompanying stone have hieroglyphic symbols. (John Stuart, Sculpted Stone of Scotland (1856). Plates I, VIII)

“Unknown scenario”

Ogham was an early medieval alphabet used to write the early Irish language between the 1st and 9th centuries. The short inscription on the Newton Stone contains 6 lines of 48 letters and symbols, including both swastikas and located on the top third of the stone. The language used to write this message has never been precisely identified, and it is known in academic circles as “unknown writing.”

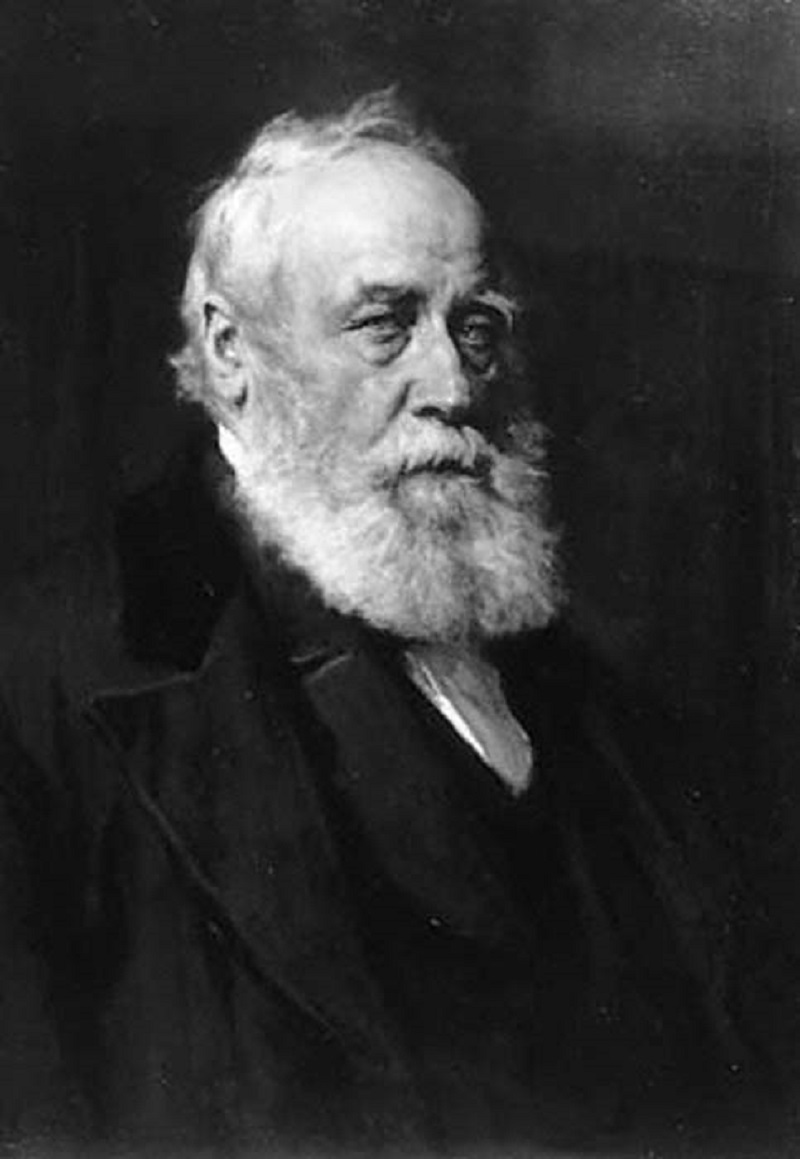

Most experts agree that Ogham’s long inscription is ancient. For example, Scottish historian William Forbes Skene dates this unknown inscription to the 9th century. But some scholars also suggest that the short row was added to the stone in the late 18th or early 19th century. 19th century, suggesting the mysterious “unknown writing” was a modern hoax or a poorly executed forgery.

Portrait (dark) of Scottish historian William Forbes Skene. ( Public domain ) He dated the unknown inscription to the 9th century.

Decoding the stone

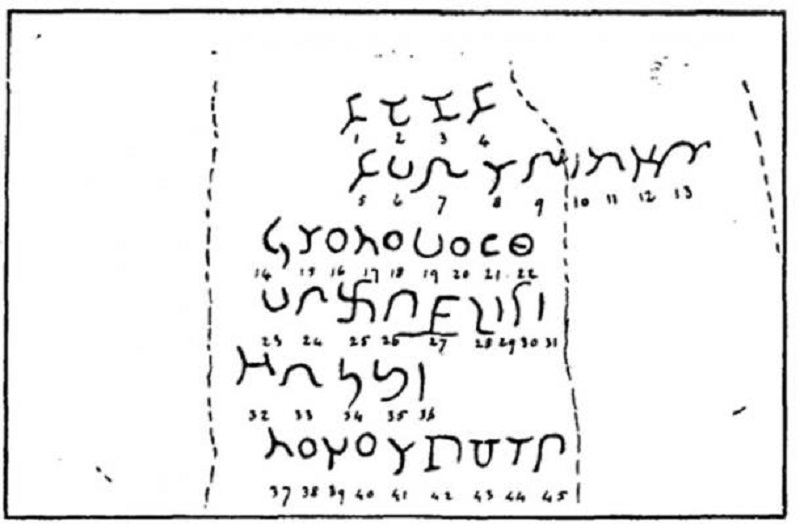

The mysterious inscriptions on the Newton Stone were first published by John Pinkerton in his book ‘Historical Investigations of Scotland’ in 1814, but he personally did not attempt to decipher the “unknown writing”. That first happened in 1822 when John Stuart, Professor of Greek at Marischal College, detailed a translation attempt by Charles Vallancey, who considered the characters to be Latin, which he published in a paper submitted to the Society of Antiquaries of Edinburgh titled ‘Sculptural Pillars of the Northern Part of Scotland.”

In 1856, Stuart published ‘The Sculpted Stones of Scotland’, detailing the work of Dr. William Hodge Mill (1792–1853), an English churchman and orientalist, the first rector of Bishop’s College, Calcutta, and was later Regius Professor of Hebrew at the college. Cambridge University. Dr. Mill proposed “the unknown Phoenician script” and was highly respected in ancient linguistic circles, his opinion was seriously considered and also much debated, nowhere none other than at a meeting of the British Association at Cambridge in 1862. Mill died in 1853, his paper was titled ‘On the decipherment of the Phoenician inscription on the Newton stone discovered in Aberdeenshire’ was read in this debate, and his translation of “unknown script” was:

“To Eshmun, God of Health, by this monumental stone, may the wandering exile of me, your servant, be remembered endlessly, even by the record of Han Thanet Zenaniah, the Judge, who is filled with sadness.”

Main inscription diagram—Newton Stone. (Yes, the Earl of Southesk)

Some scholars support Mill’s Phoenician theory, for example, both Dr. Nathan Davis, the explorer of Carthage, and Professor Aufrecht also believe that the script is Phoenician. But in the skeptical camp, Mr. Thomas Wright proposed a simpler ‘lower Latin’ translation, reading: hie acet Constantinus, “This is Constantine, son of.” Mr. Vaux of the British Museum agreed that it was ‘medieval Latin’ and Wright’s translation was also supported by the paleontologist Constantine Simonides, but he replaced the Latin with Greek.

Three years after this failure, in 1865, antiquarian Alexander Thomson read a paper to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland mentioning the five most popular decoding theories:

• Phoenicians (Nathan Davis, Theodor Aufrecht, William Mill)

• Gaelic (anonymous correspondent for Thomson’s)

• Latin (Thomas Wright, William Vaux)

• Greek (Constantine Simonides)

• Gnostic symbol (John O. Westwood)

Close-up of the undeciphered inscription on the Newton Stone. (golux/ Megalithic Gate )