Due to fluctuations in the earth’s temperature, sea levels around the world rose and fell more or less steadily during the Pleistocene between 400,000 and 12,000 years ago. During times of very low temperatures, large amounts of water freeze and deposit as ice in northern regions of the world, causing sea levels to drop up to 140 meters (459 ft.) lower than today. now. This is the Ice Age, of which there were four ice ages during the Pleistocene. As this happened, vast areas of land around the world less than 140 meters below sea level were exposed during the Ice Age. As sea levels rise again during warmer periods, these lands are submerged by rising seas and disappear underwater. For the Mediterranean islands of Malta, this means that during the last Ice Age, when sea levels sank up to 140 meters, they were connected to Sicily by a strip of land. At the height of the last Ice Age, Malta and Sicily formed one vast landmass.

Malta and Sicily, 20,000 – 12,000 BC. Image courtesy of Lenie Reedijk

The first humans arrived in Sicily about 24,000 years ago, at the height of the last Ice Age, when a land bridge between Malta and Sicily existed. The distance between the southeastern point of Sicily and Malta is 80 kilometers (49.7 miles). People living in Sicily who wanted to reach the land now known as Malta could do so on foot in a few days. That’s an option.

Ancient seafaring in the Mediterranean

However, the earliest evidence of seafaring in the world has been found in the Mediterranean region. Crete in the Aegean has been an island for the past 5 million years and has never been connected to any other landmass in human history. However, up to 2000 stone tools, among them Lower Palaeolithic handaxes, have been found on its southwestern coast in contexts believed to date back at least is 130,000 years old and possibly even 190,000 years old. The makers of these tools could only reach Crete by boat. The New York Times, in reporting on these findings, quoted archaeologists and experts who were astonished:

“…this discovery seems to suggest that these ancient sailors had stronger and more reliable craft than rafts. They must also have had the cognitive ability to form and make multiple sea crossings over great distances to form sustainable populations, producing countless stone artifacts.”

If seafaring in the Mediterranean is proven to go back to these extremely remote times, we can assume that people could have reached Malta from Sicily easily, either on foot or by boat. from more distant places.

Evidence of Paleolithic humans in Malta

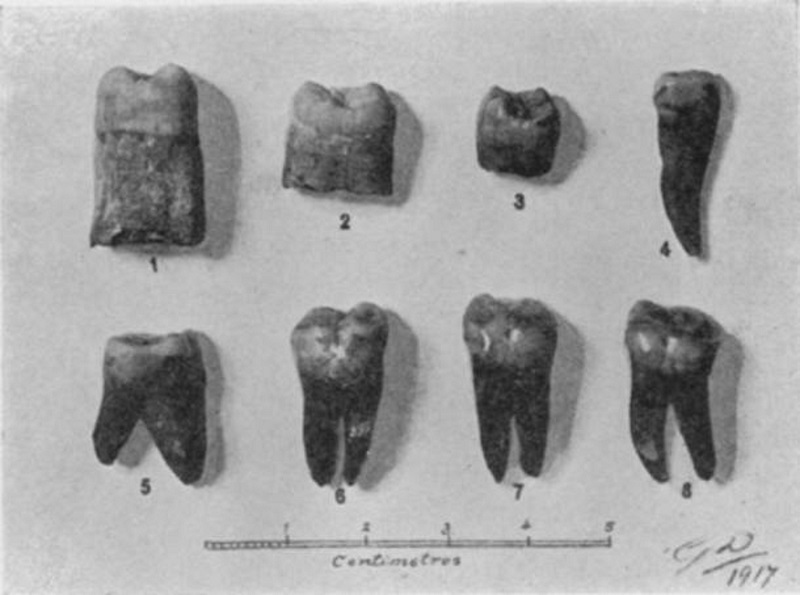

The presence of Paleolithic humans in Malta was once widely accepted by domestic and foreign researchers as a proven fact. Convincing evidence for that was found in two fossil teeth with fused roots (called ‘taurodonts’ in the literature), attributed to Neanderthals and debunked by Maltese paleontologist Giuseppe Despott. excavated in 1917. They were excavated in the Għar Dalam cave in southern Malta, in a layer that contained no ceramics but instead flint and obsidian. A third tooth with similar characteristics was found by compatriot JG Baldacchino in 1936. Thorough investigations of the cave were dynamic and carried out by experienced hands. During those glorious pre-war decades, Malta was famous among experts worldwide for its ancient temples as well as for its Paleolithic ruins, in which humans are still considered to have their rightful place. worth.

Photograph of Dr. Despott’s teeth found in 1917. (Sir Arthur Keith)

Covers the early human presence in Malta

The War of 1939 ended all research into Malta’s Paleolithic past. Although enemy action caused damage to many antiquities on the archipelago, none of this can compare with the setbacks received at the introduction, immediately after the war, of the review tells the whole story of Malta’s distant past.

One step towards achieving this is to remove from all future publications any reference to a human presence during the Ice Age in Malta. Instead, the story of the settlement of Malta by a group of Neolithic farmers around 5,200 BC was introduced, accepted and then cast into stone. How this version of history could have been accepted in Malta for so long remains, in retrospect, a mystery. Nor is it easy to understand why any broader view, no matter how well researched, has been met with implacable resistance ever since.

Human presence can be detected in many ways. First, there are skeletal remains, which give us a direct indication. Second, human-made artefacts and works of art are direct evidence that they were present at the scene. Third, and most overlooked in our Maltese context, there are traces of human activity that indirectly but clearly indicate their presence. Although they are signs by inference, they are no less important. These include:

Piles of carcasses and body parts of edible animals, large or small

Animal bones found in places that would not normally be their habitat, such as elephants, deer or swans in caves, crevices or surface crevices

Pile of broken seashells in a landlocked area

Bones, especially long bones, are broken to remove marrow

There are signs of strong impact on parts of the skeleton, such as the elephant’s teeth being broken in half, and stones still stuck in the jaw.

Skeleton and skull at Għar Dalam Museum. (Continental Europe/ CC BY SA 4.0 )

All these cases, which can be said to be the smoking gun of any detective’s dream, were reported in Malta by various investigators at times when curiosity and research were still alive. Handsfree.