We all remember the daring, thrilling novels about pirates, buried treasure and exciting sword fights that fired our imaginations when we were such children. any. Iconic novels like “Treasure Island” by Robert Luis Stevenson, or “Peter and Wendy”, “Desert Island” and “Billy Budd” have all transformed our childhoods and made us dream about great adventures. But what about the truth behind the fiction? What about real-life pirate adventures and hidden gold?

Today we’re exploring the real-life inspiration behind these fictional adventures, as we look at the story of the legendary Treasure of Lima. What secrets lie in mysterious tropical islands in the Pacific? And will the secret of the legendary gold treasure of the Incas ever be discovered?

Enemy at the Gates – The Catholic Church tries to save the treasures of Lima

The story of Lima’s greatest treasure begins around the 16th century, when Spanish conquistadors finally conquered the Incas and established their rule over Lima and its territories. The previous Inca Empire. Now the main desire of the Spaniards in their conquest was gold. And if the Incas had large quantities of anything, it was gold.

Ancient Peruvian mask made from gold. (Carlos Santa Maria/Adobe Stock)

Over the following decades and centuries, the Spanish, especially the Catholic Church, amassed large amounts of gold – in the form of coins, bars, and other artifacts – as well as gems, jewels, and jewelry. energy and all kinds of valuable things. Among these legendary treasures are large golden crosses exquisitely crafted with precious stones, and it is even said that the Spanish created life-sized effigies of Saint Mary and the Apostles in solid gold and studded with precious stones.

There are also many other gold and silver objects – holy grails, gold bars, Inca gold relics, 273 jeweled swords and many others. During that time, it was worth about $60 million. But today that value would be more than a billion.

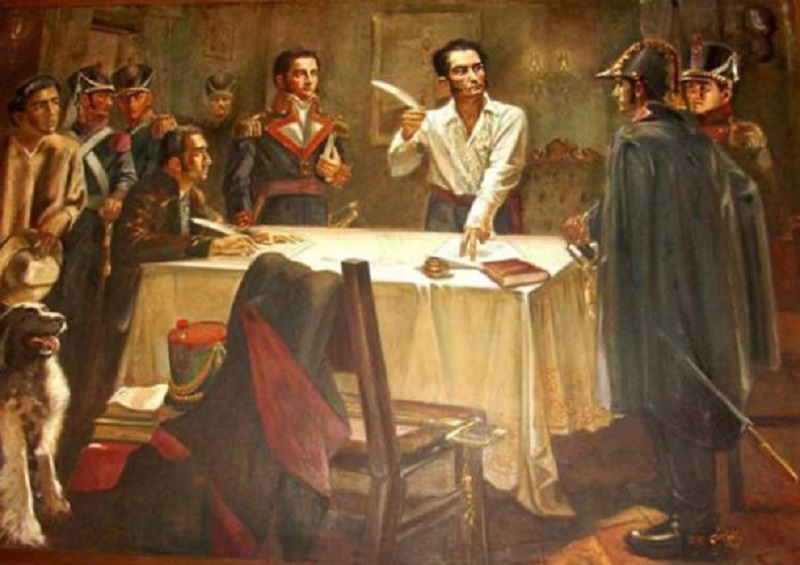

But when the Wars of Independence in South America began to break out in the early 19th century, panic quickly arose among high-ranking Spanish officials. With the beginning of the Peruvian War of Independence (c. 1811-1826), Lima itself became a target and in 1820 the city had to be evacuated. In the following year, 1821, the revolution’s leaders, Simón Bolívar and José Francisco de San Martín, aimed to conquer Lima, and in the process gain access to vast wealth. accumulated by the Empire and the government. Church. San Martín gained partial control of Lima on July 12, 1821, but the treasure was not there.

Liberator Simón Bolívar signs ‘Decree of War to the Death’. (Public domain)

Fearing mass looting by the revolutionaries, Spanish officials, with Lima Viceroy José de la Serna at their head, decided to play a game of cards and try to preserve the enormous treasure. Their plan was to move the treasure to the port of Callao and hire a merchant ship to help them “smuggle” the treasure out to sea. Once there, the ship would wait for Lima’s fate to be decided. If the revolutionaries are defeated, the treasure will be returned.

The merchant ship they chose was the “Mary Dear,” a conflict-neutral British merchant ship from Bristol, with Captain William Thompson at its helm. This plan was a gamble from the beginning, but the Spanish were desperate and had to rely on Thompson and his crew.

William Thompson. (Keith Thomson)