The mystery of how the Pyramids of Giza in Egypt were built continues to baffle scholars, even in the 21st century. As the famous Egyptologist Flinders Petrie recorded in The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh (1883): “The means used to lift such blocks of stone are not presented to us in any model. What description? The world’s brightest minds still struggle with competing ideas, making educated guesses based on incomplete evidence.

Every theory begins with an inclined plane, or pyramid-shaped ramp. This idea was first mentioned two millennia ago by the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who recounted what the Egyptians had told him about the pyramids: “It is said that… Construction was carried out with the support of earth slopes, as at that time cranes had not yet been invented.” (History Library 1. 63).

Many theories for the pyramid ramp

In the late 19th century, Petrie carefully measured the Giza Pyramids, especially the Great Pyramid of Khufu, and determined that the most suitable way of construction was to use a single, long ramp, with a smaller zigzag ramp near the summit. Since then, this idea has been largely discredited due to lack of evidence, and other theories have replaced it.

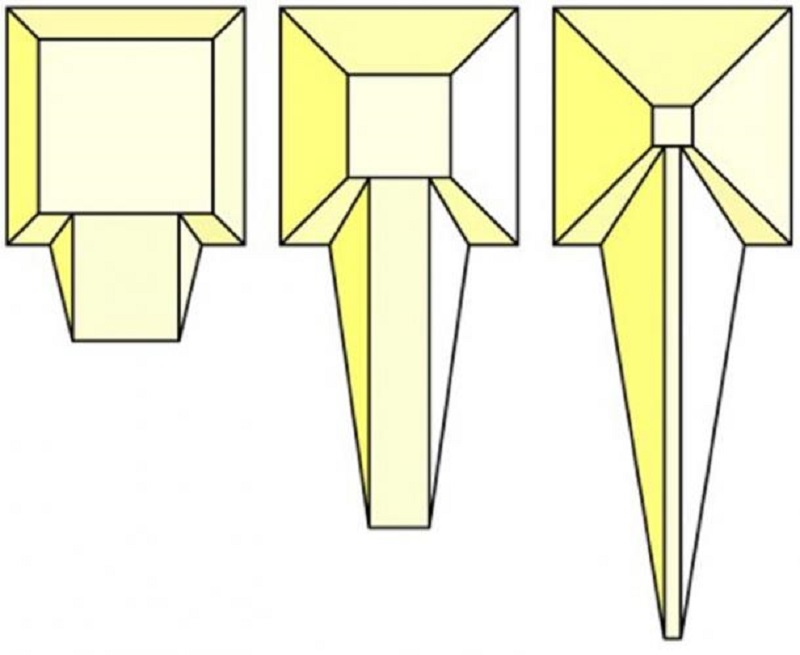

Three types of straight, single pyramid ramps for construction may have been used in the construction of the ancient site. (Smuckola / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

The late German Egyptologist Uvo Hölscher believed that the Egyptians used a short ramp that snaked across the face of the pyramid, while Dieter Arnold, the German archaeologist who wrote the famous Work in Egypt (1991) believe that a long ramp was used, but it cut through the center and was partly composed of the pyramid itself.

Meanwhile, Giza archaeologists Zahi Hawass and Mark Lehner believe that the clearest physical evidence points to a spiral ramp that may have spiraled up the outside of the pyramid, resting against the structure or on a large mound. They suggest that water or milk may have been used to lubricate wooden sleds tied to stone blocks, similar to the scene in the tomb of Djehuti-hotep in the Middle Kingdom (~1900 BC).

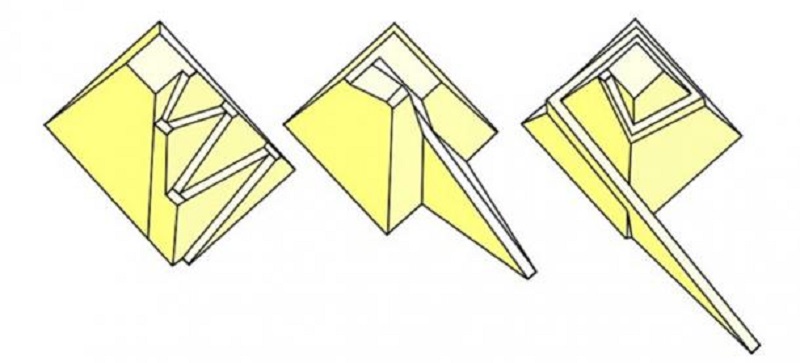

Three different pyramid ramp proposals, by Uvo Hölsher (left), Dieter Arnold (center) and Mark Lehner (right). (Althiphika / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Many recent experiments have confirmed this possibility, including a 2014 study by Daniel Bonn and other scientists from the FOM Foundation and the University of Amsterdam that demonstrated that the right water-to-sand ratio can reduce half of the people need to pull a block. There is also a depiction on a New Kingdom stele showing six oxen pulling a load on a sledge (~1575 BC), and many actual sledges have been recovered.

What about evidence?

Evidence of land ramps exists in Egypt. The best example comes from the Temple of Karnak in Thebes, which can still be seen leaning against the back of the towering First Pagoda. Made of mud brick, it was never completely disassembled and today it stands as a testament to the way in which these large stone structures were built and decorated. Other examples come from the abandoned step pyramid of Sinki in Abydos. Apparently built by Huni, Sneferu’s father and Khufu’s grandfather, the pyramid has four construction ramps still intact, consisting of two outer mud-brick walls with an interior filled with debris and stones. chips.

Ruins of an ancient mudbrick ramp at the Temple of Karnak in Thebes (First Tower, New Kingdom). ( Vermeulen-Perdaen / Adobe stock)

Surprisingly, the potential construction ramp of the Great Pyramid has been discovered and it is similar to other ramps. In 1995, Inspector Giza “excavated trenches through thick layers of limestone south of the southwest corner of Khufu’s pyramid. Remains of stone walls were found running north-northwest, possibly as fill or retaining walls of the foundations of a supply road (for example). (Lehner, 2017; 440).

According to Hawass, the lower part of this ramp: “consists of two walls built of crushed stone and mixed with “tafla” (a calcareous clay). The area in between was filled with sand and plaster, forming the bulk of the ramp.” (Hawass, 1998; 58). He calculated the ramp would be ~30m (98ft) higher than the base of the pyramid, or about 20% of the pyramid’s original total height of 146.7m (481.3ft). Additionally, he believes the ramp will spiral up the outside of the structure.

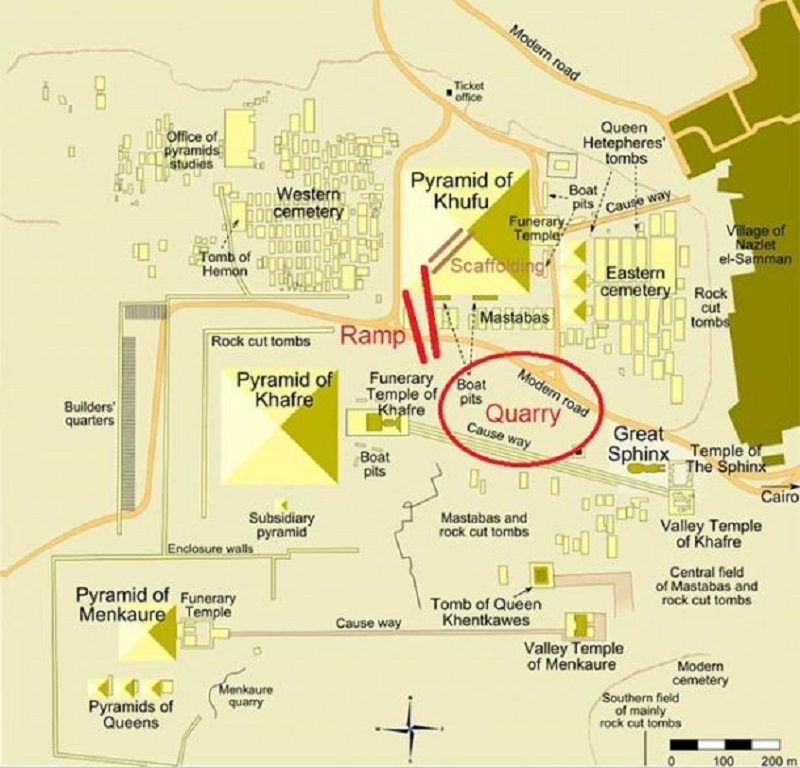

Map of the Giza Plateau, showing the newly discovered ancient ramp in the red line at the southwest corner of Khufu’s pyramid, and the author’s proposed wooden scaffolding running to the top (red and brown lines added by the author). (MesserWolland / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

In late 2018, the remains of a ramp were found at an ancient gypsum quarry in Hatnub, from the time of Khufu. It reveals how the Egyptians were able to move extremely heavy blocks of stone using physics to assist them. Archaeologists from France’s Institute of Oriental Archeology and the University of Liverpool have excavated a ramp with steps on either side and with post holes near the stairs running all the way up the ramp.

The excavation team proposed that by using ropes tied around wooden poles, ancient workers could pull large blocks much more easily by using gravity to pull down instead of up. They can also maneuver the blocks better, imagined as lying on wooden sleds attached to ropes.

The ancient ramp discovered at Hatnub, Eastern Egypt, in 2018, has a similar shape but is smaller in size than the pyramid ramps that may have been used to build contemporaneous sites. in Giza. (Yannis Gourdon / IFAO )

Adding ropes and wooden poles to change the direction of the force can effectively double the slope, meaning any ramp on the pyramid only needs to be half the size of its intended size. its determination. their. This would double the slope of the Khufu ramp, discovered in 1995, to ~60m (197ft), or 40% of the pyramid’s original height (and most of its volume).

However, the problem still exists. A spiral ramp around the pyramid would be impractical because of the impossibility of looking back at each corner for authenticity, its enormous size (rivaling the pyramid itself), and lack of any archaeological evidence. Which neck? So if the builder uses a ramp, where is it? An ingenious architect named Jean-Pierre Houdin thinks he has the answer.

A hidden ramp inside

Perhaps no other hypothesis in recent years has attracted as much attention as the ‘inner ramp’ of the Great Pyramid, an idea proposed by French-British architect Jean-Pierre Houdin first appeared in 2005. Aided in his expedition by Egyptologist Bob Brier, they flew to Egypt to search for evidence of this proposed interior ramp.

In essence, Houdin proposed that the Egyptians built an internal ramp just inside the structure’s perimeter, curving up as the pyramid rose, including a bell-shaped ceiling and a fluted ceiling. the angle at which the blocks will be rotated on the rope crane. This would seemingly eliminate the need for external ramps, levers, cranes or scaffolding.

Several lines of evidence have been put forward by researchers as evidence for their ideas. First, Houdin discovered faint ‘ghost’ lines within the pyramid’s masonry running at an angle of ~7°, the exact angle at which he determined the interior ramp should run.

Second, there is a mysterious ‘notch’ on the northeastern edge of the pyramid, which Houdin predicted was an early ‘angle station’. This ‘notch’ was explored by Brier, who found an unusually small room (“Bob’s Room”) but nothing more than that.

Third, in 1986, a French team completed a microgravity study of the pyramid and the resulting CG images of the low- and high-density areas showed images consistent with a inside ramp.

Fascinating theory but where is the evidence?

Although this theory initially seems appealing, many consider this an unlikely scenario. Egyptologist David Jeffreys called it “far-fetched and terribly complex,” as it suggests the pyramid was much more complex than is currently believed. Instead of having four rooms and hallways inside, it will actually have dozens of rooms inside. Instead of having one impressive Grand Gallery with bells, it would have had the equivalent of over thirty large galleries running along the monument, all corridors lined with impressive stone bells.

It seems absurd, considering the Grand Gallery itself is an incredible feat, that there are still thirty more statues to discover somewhere inside the pyramid, all connected to each other. And despite plenty of circumstantial evidence, Brier and Houdin have yet to find any concrete data specific to their ramp. Even their much-vaunted microgravity scan can be interpreted differently, for example through an internal ‘steps’ model.

Grand gallery in the Great Pyramid of Giza. Houdin’s theory would require 30 more of these inside the pyramid. (Keith Adler / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Now, despite the conceptual difficulties, it remains a promising theory that needs independent verification. Fortunately, the ‘Scan Pyramids Mission’ ( scanpyramids.org ) will be its final test. Started in 2015, this research is based on the idea of using cosmic particles called muons to remotely scan the pyramid for voids, an idea first used by famous physicist Luis Alvarez in the late 1960s on Khafre’s pyramid.