The fact that India has thousands of megaliths is something that deserves to be more widely known. These monuments include Menhirs (tall standing stones), arrangements, avenues, stone circles, cysts, dolmens, burial mounds, stone cutting chambers and more. Professor KP Rao, Professor of History at the University of Hyderabad is a great authority on these monuments and he estimates there are several thousand sites, each of which contains from 10 to 50 stones and several The complex contains up to 2000 to 3000 stones. Overall, India may have more monuments of this type than all of Europe.

These monuments date from 1400 BCE to 200 BCE, and thus belong to a more recent culture than that of the European megalith builders, dating from 4500 to 1500 BCE.

Smaller alignment stone – Madumal. (Photo provided by Professor KPRao, University of Hyderabad)

Construction of megaliths

The relationship between the megalith builders and religious practices in south India is complex and ripe for further explanation. It is commonly believed that the megaliths were the work of various tribal groups in India, who left behind little or no literary records. By contrast, what we might call the “great” tradition of India has a very large body of texts. The Bible and early Indian mythological literature indeed sometimes mention megaliths. For example, there are a number of highly respected epic poems of South India, products of the Tamil Sangam era, which take their name from a gathering or gathering of three hundred Tamil poets and scholars who was “swept away by the sea”. The late Kamil Zvelebil, a respected scholar of Tamil culture, opined that the gathering was indeed a regular occurrence. The time frame for the Sangam era is usually placed around 350 BC to 300 CE and would coincide with the final stages of megalithic construction.

Sage Agastya, President of the first Tamil Sangam, Thenmadurai, Pandiya Kingdom. ( CC BY-SA 2.5 )

One of the most famous works of this Sangam era is Manimekalai, an epic poem, which lists several types of burial practices. There are “Crematologists, who dispose of or expose the dead to nature or animals. Those who place the bodies in holes they dig into the ground, those who bury the bodies in cellars or underground vaults, and those who place the bodies in a burial urn and turn the lid upside down.” (Ch 6.11, 66-67)

A palm leaf manuscript with ancient Tamil text (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Since this Sangam era, Hindu India has become more famous for cremations than mausoleums, although some contemporary Hindus, wish to break the widespread taboo against murder, took these ancient practices as a precedent.

Manimekalai tells the story of a beautiful prostitute, the eponymous heroine of the poem. This is a sequel to The Story of the Anklet (The Silappatikaram) which I discuss in detail in my book “Isis, the Egyptian and Indian Goddess”. Manimekala is the “illegitimate” daughter of Kovalan and Madhavi; the femme fatale with whom he had a disastrous liaison and affair. After an eventful life, including an encounter with the Sea Goddess, whose name she also bears, she converted to Buddhism.

Burial of tribal leaders and heroes

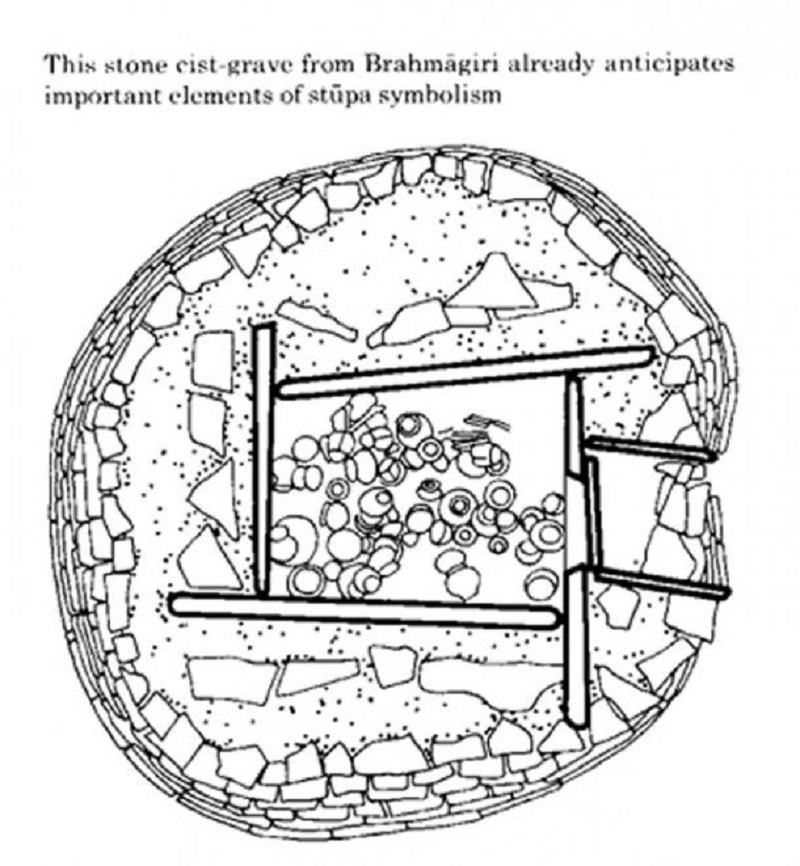

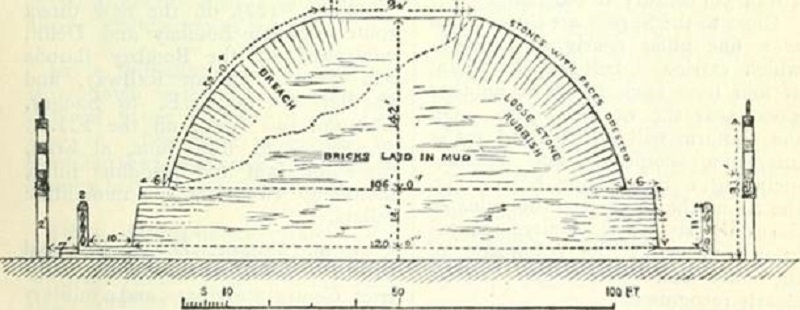

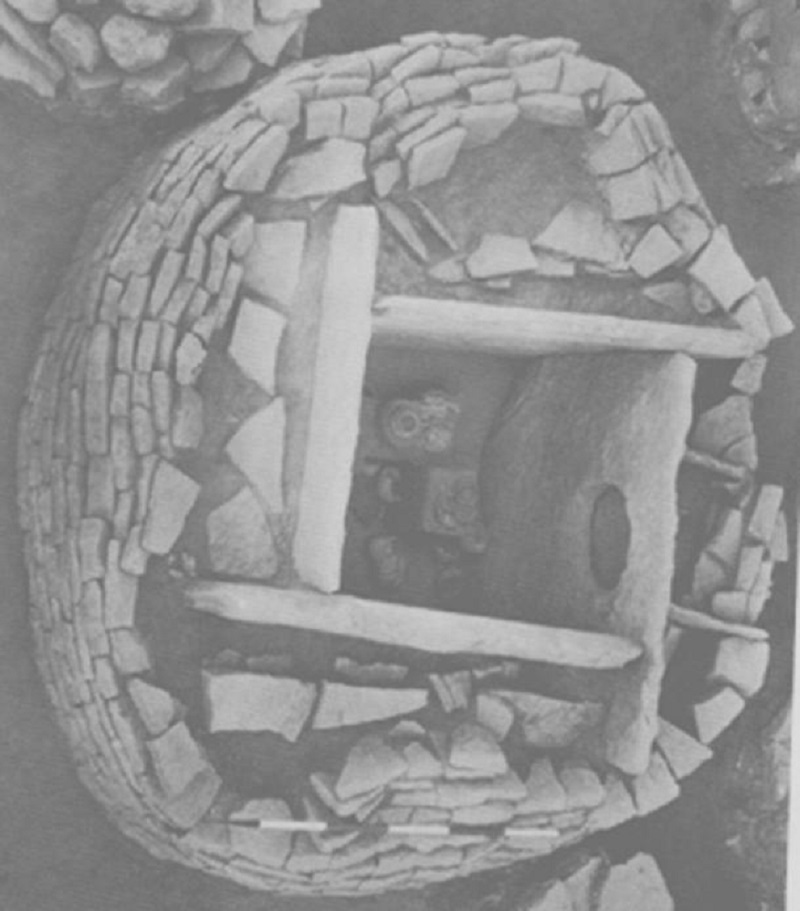

The Buddhist context is important because there is an interesting connection between Buddhism and the megalith builders of India. Consider the burial mounds that abound in peninsular India. The following images from the research of British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler show the construction of the square room by placing four orthomosaic panels, one of which has a window opening. If you look at the overall shape from above, you can make out the swastika. The swastika is a powerful Sanskrit word with no apparent meaning other than a completely benign and auspicious image.

Cist Burial Place – from Brahmagiri, which has thousands of similar monuments, porthole, 1.5-2ft diameter, facing east for sunrise – it is too small to be an entrance but is approached by a downward ramp and potentially a spirit-door to allow communication between the worlds of the living and the dead. (Source Mortimer Wheeler, My Archaeological Mission to India and Pakistan, London 1976 p. 61)

Drawing of the same tomb – from Andreas Volwahsen, Living Architecture Indian London 1969 p. 90

It is entirely possible that this swastika symbol, revered by Hindus, Buddhists and Jains, has an older origin dating back to the megalithic builders, a symbol that may have been transferred assigned to the founders of this religion, all of whom spent time in remote, jungle retreats, often with tribesmen who may have built the megaliths.

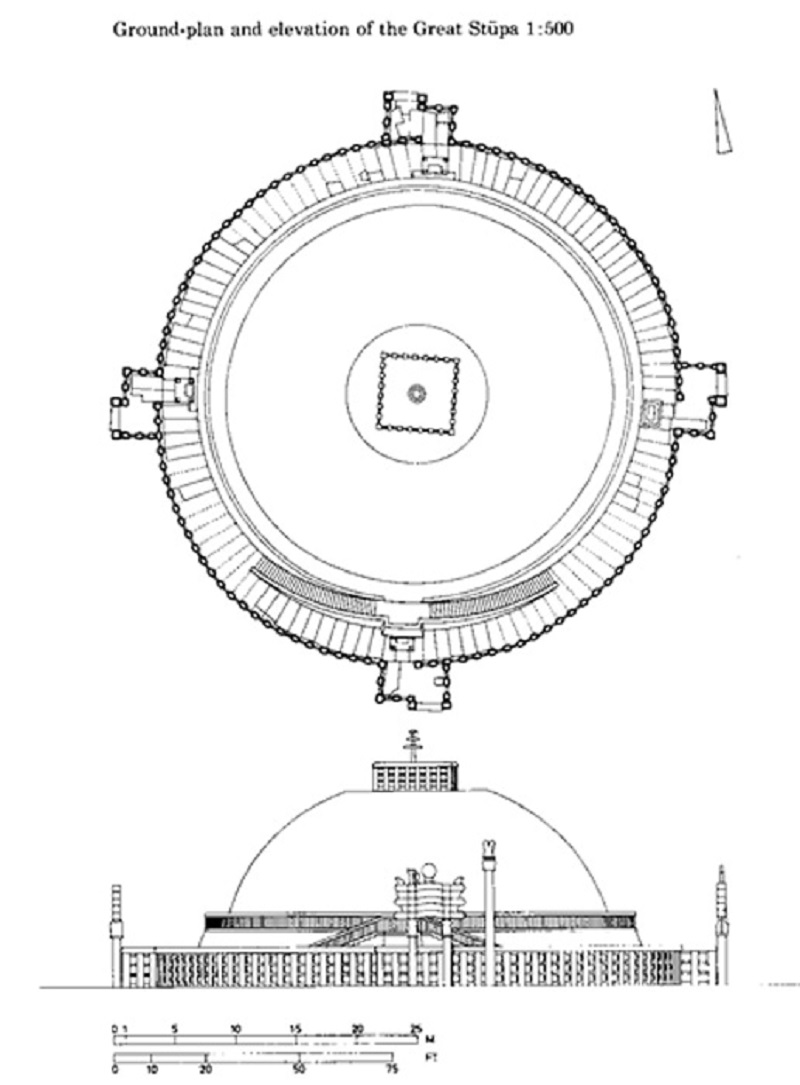

According to Andreas Vohwahsen, cist tombs were mainly for tribal leaders and heroes. It is significant that the Buddha instructed his disciples to commemorate the great kings and sages by erecting, at crossroads, so-called stupas, mounds of earth surrounding a relic. Early Buddhist texts say that after the Buddha’s death, eight princes fought among themselves for his ashes. Each person built a giant egg-shaped stupa or mound to house them.

The floor plans of these stupas reflect the floor plans of the megaliths. In addition to the swastika-shaped plan and egg-shaped dome, there is also a square room inside the ritual containing human remains. As a macroscopic model of the human body, the outer path ( medhi ) is the abdomen, the egg-shaped dome ( anda ) is the upper body, and the umbrella over the vase represents the head. Mushroom or umbrella-shaped stones also appear in older megalithic tombs. The full influence of megalithic burials can be seen in the following diagram of a stupa.

There are other symbolic connections between megalithic culture and what one might call the more heterodox religious trends in India – Buddhism, but also what we call Tantra. The origins of Tantra may also overlap with those of the megalith builders in India. Some of the more “extreme” Tantric practices involve meditation in open ground or cremation grounds; where corpses are stored overnight and then cremated. KR Shinivasan reminds us that the original meaning of smashana was a stone bench, i.e. a tomb. So perhaps the original impetus for Tantra was one of a long list of ancient practitioners whose core practices involved communion with the dead.

Astronomical meaning: Sun, moon, stars

Although the builders of the megalith left no literary remains, many signs have been found on stones and pottery in the tombs. Many appear to have astronomical significance, depicting the sun, stars on the moon, and directions. Megalithic tombs are highly political, oriented according to compass points. The window, an example of which is shown in the cist photo, was too small to accommodate the body and must have been equivalent to a spirit door so that the living could continue to communicate with their ancestors. These windows also allowed the rising sun and perhaps other stars to illuminate the tomb at dawn during important “twilight” times of the year, especially the winter and summer solstices.

The Sky Religion, what Professor Rao calls “megalithism,” remains a living tradition among many tribal groups in India. There are 645 tribes defined by the Indian constitution. For example, the Gonds, who worshiped the sun, moon and stars and offered symbolic human sacrifices (see Bahadur 1978:89 “caste, tribe and Indian culture”, were quoted in KP Rao.)

Many tribal groups still erect menhirs to commemorate the dead, often in response to the appearance of a deceased ancestor who was once a troublesome ghost. A religious expert, a “shaman”, asks them what they want, which turns out to be always a party and the erection of a menhir to bring them respect among other ghosts. For anyone who has studied the folk magic of Egypt or Sudan, this is very familiar territory. This seems completely similar to the funeral customs of many other cultures, including our own, where funeral stele are still erected to commemorate the name of the soul of the deceased. We are dealing with a universal human nature.

Chris Morgan is a respected independent scholar, a Wellcome alumnus and holds an advanced degree in Oriental Studies from Oxford University. He is the author of several books on Egypt, specializing in folk religion, ritual calendars, and the “archaeological memory” encoded in the religions of post-Pharaonic Egypt. He was also an Indologist, interested in Indian philosophy and technology, especially Ayurvedic medicine and folk magic traditions. His latest book is “Isis: Goddess of Egypt & India.”