In a remarkable revelation from a recent study, ancient Egypt once again defied expectations, demonstrating its globalized nature even during the early Bronze Age. Research focusing on the glamorous silver bracelet that adorned the wrist of Queen Hetepheres I from the Fourth Dynasty, has revealed a trade network between ancient Egyptians and Greeks dating back to 2600 B.C. These findings challenge previous assumptions, shedding light on long-standing and extensive trade relationships that extended beyond Egypt’s borders. From the enchanting Cycladic Islands to bustling Lavron in Greece, these discoveries paint a vivid picture of a world interconnected through trade and treasure.

A lasting connection: Trade and treasure

The study, published in the renowned Journal of Archaeological Science, analyzed silver artifacts from ancient Egypt, revealing the trade network with the ancient Greeks was not only more extensive but also older. significantly more than previously believed. It seems that the ancient Egyptians were actively involved in a trade network that grew far beyond their borders.

Trade routes stretched through the Bronze Age Cycladic Islands, Greek cities nestled in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), the enchanting island of Crete, and bustling Lavrion on mainland Greece.

“Egypt has no domestic sources of silver ore, and silver is rarely found in the Egyptian archaeological record until the Late Middle Ages,” write the authors, a team of archaeologists from Australia, France and the United States. middle”. “Surprisingly, lead isotope ratios are consistent with ore from the Cyclades (Aegean islands, Greece) and to a lesser extent from Lavrion (Attica, Greece), and are not separated from gold or electricity as previously assumed. This. Sources in Anatolia (West Asia) can be ruled out with high confidence,” the report authors wrote.

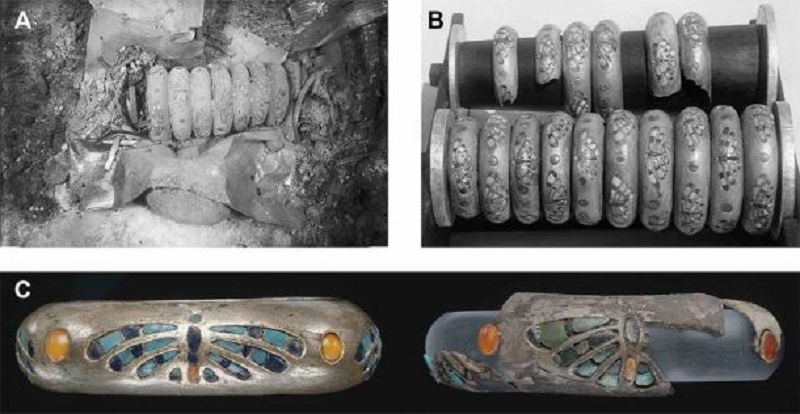

(A) The bracelets in the burial chamber of Tomb G 7000X were discovered by George Reisner in 1925 (Photographer: Mustapha Abu el-Hamd, August 25, 1926) (B) The bracelets in the frame were restored, Cairo JE 53271–3 (Photographer: Mohammedani Ibrahim, August 11, 1929) (C) A bracelet (right) in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MFA 47.1700. The bracelet on the left is an electronic reproduction made in 1947, MFA 52.1837 (Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition; All photographs © Museum of Fine Arts April 2023, Boston).

These beautiful silver artifacts were forgotten without thorough analysis for decades until now. The report’s lead author, Karin Sowada from the Department of History and Archeology at Macquarie University in Sydney, led this groundbreaking research and report.

“This type of ancient trading network helps us understand the beginnings of the globalized world,” Dr Sowada told the ABC. “For me it was a very surprising finding in this particular discovery. Egypt is famous for its gold but has no local silver sources. Dr. Sowada continued: This early period of Egypt was an unknown land from the perspective of silver. She added that these bracelets were “essentially the only large-scale silver that existed during this period of the third millennium BC.”

Queen Hetepheres: Daughter of God – A Hidden Mystery

Queen Hetepheres, known as ‘God’s Daughter’, held an important position as the direct royal bloodline of the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, during the Old Kingdom period that lasted from 2700 BC to 2200 BC. She married King Sneferu and gave birth to a son and successor, Khufu, who built a large tomb and pyramid as her eternal resting place.

For centuries, the burial place of Queen Hetepheres remained a mystery until its accidental discovery in 1925. Explorers stumbled upon a previously hidden crypt in Giza, where they discovered her empty coffin. While Hetepheres was initially believed to have been laid to rest near her husband’s pyramid at Dahshur, her son, Khufu, ordered her tomb moved to Giza after it was targeted by tomb robbers.

The exact location of Queen Hetepheres’ body and other precious artifacts buried with her is unknown. Dr. Sowada emphasized that “it is these objects that give us a glimpse into her life and how she lived.”

Research and Analysis: An elegant science

To delve into the secrets of these ancient artifacts, the report’s authors meticulously examined samples from the collection housed in the famous Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Using advanced techniques such as bulk XRF, micro-XRF, SEM-EDS, X-ray diffractometry and MC-ICP-MS, they successfully detected essential mineral and elemental compositions . Additionally, the team used lead isotope ratios to gain valuable insights into the nature, metallurgical processing, and possible source of the silver ore.

To their surprise, analyzes revealed the presence of silver, silver chloride and possibly even traces of copper chloride in the minerals. However, it was the lead isotope ratio that surprised them. These proportions correspond only to those found in silver originating from the Aegean, Attica, and Anatolia—areas that flourished during the Bronze Age, before the Hellenistic period.

Hetepheres Bracelet I. Parts of two silver bracelets (about one-third preserved) with parts of two butterflies set in turquoise, lapis lazuli, and carnelian (© Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition )

Further examination of the cross-section of the bracelet fragment owned by Queen Hetepheres has provided fascinating details about the craftsmanship involved in creating these ancient treasures. The metal apparently went through annealing and cold forging multiple times during the complex fabrication process, ABC revealed.

Perhaps the most important finding to emerge from this study is the compelling evidence that Egypt and Greece engaged in long-distance trade much earlier than previously known. In fact, this study provides the first scientific evidence that silver originated in the Aegean Islands in Greece, revealing a previously unknown aspect of their ancient trade networks.

While more information about Egypt’s trade networks is recorded during the Middle Kingdom (2040 BC – 1782 BC) and New Kingdom (1550 BC – 1069 BC), the application of lead isotope analysis for silver objects from the Middle Kingdom is the biggest lesson from this study.

Dr Gillan Davis from the Australian Catholic University, one of the authors, told the ABC: “In the Middle Kingdom and the much later New Kingdom, we have a lot of papyri containing administrative records, records commercial, etc. “But for the Old Kingdom, it’s been so long that those documents largely no longer exist,” she concluded.

Above: Below, Hetepheres bracelet at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MFA 47.1700. Top, an electrical copy made in 1947, MFA 52.1837 (Harvard University—Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition) Source: © April 2023 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston/ Journal of Archaeological Sciences archeology