In 2012, a citizen alert brought the Mexican police to a cave on the Guatemalan border where a horrific cave sacrifice scene met their eyes. Some 150 skulls and other human skeletal remains lay piled up in the cave in the municipality of Frontera Comalapa in southern Chiapas state, according to the New York Post. At first, the police thought the Chiapas cave sacrifices were a grisly modern mass murder. The conjecture wasn’t far-fetched, given that the Mexico-Guatemala border area is a famous area for modern human trafficking and extreme violence.

Now, after a decade of chemical analysis and investigation of the remains collected from the Chiapas cave sacrifice scene, in collaboration with the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), has led to a radical revision of the original police theory. A recent INAH press release announced that the investigation has shown that the cave sacrifice remains in fact pre-Hispanic. They are believed to date to the Early Postclassic period (AD 900-1200), according to Fox5.

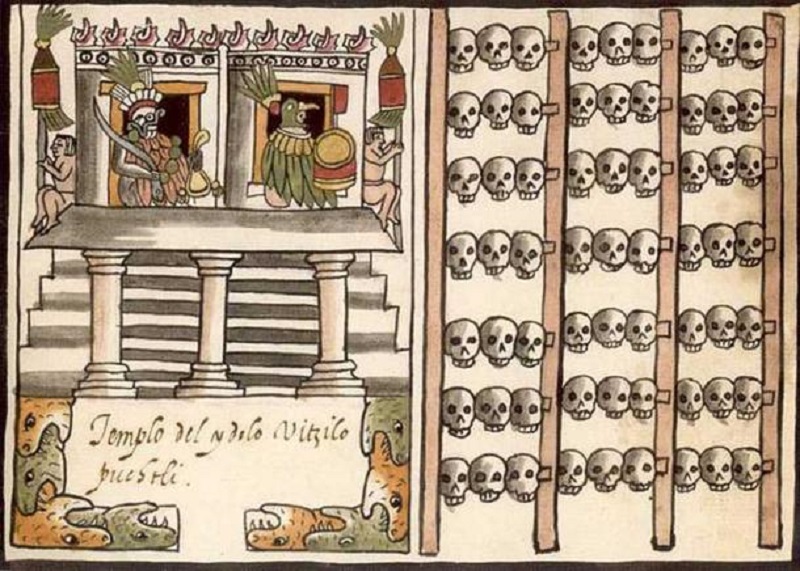

The Chiapas cave sacrifice scene also contains the remains of a wooden altar display structure, known as a or tzompantli, shown here, but the Chiapas skulls were mounted on top of poles and therefore were not perforated through the temples. (Picyrl / Public domain)

The Chiapas Cave Sacrifices: Remains of a Ritual Death Altar

The initial suspicions of the Mexican police that the skulls were part of a recent mass murder, were influenced by the fact that the skulls did not display the typical characteristic of most pre-Hispanic human sacrifices in Mexico, where skulls would be perforated on either side to mount them on a display rack.

However, experts examining the cave sacrifice skulls and what was found around them have concluded that the victims had been ritually beheaded. The INAH press release states that the scientists believe that they are from a thousand-year-old funerary context and that in fact a sacrificial altar or tzompantli, a kind of trophy display rack, exists in the Comalapa cave. The accounts of Spanish conquistadors in the 1520s mention seeing such tzompantli.

Physical anthropologist Javier Montes de Paz, a researcher at the INAH Chiapas Center, said in the INAH press release that there are several factors supporting this hypothesis. One is that while some femur, tibia and radius bones have been found along with the skulls, until now not a single complete skeleton has been identified. This lends weight to a ritual beheading context. “We still do not have the exact calculation of how many there are, since some are very fragmented, but so far we can talk about approximately 150 skulls.”

The scientists also point to the record of the Chiapas State Attorney General’s Office from 2012 that mentions traces of aligned wooden sticks. The skulls of human sacrifice victims in Aztec and other indigenous cultures were usually strung up on wooden poles using holes hammered into their temporal and parietal bones. However, experts believe the cave skulls might have rested at top poles instead, which would account for the absence of perforations. “Many of these structures were made of wood, a material that disappeared over time and could have collapsed all the skulls,” stated Montes de Paz in the INAH press release.

A closeup of one of the Chiapas cave sacrifice victims, who were mostly female for some reason. (YouTube screenshot / USA Today)

All the Victims Had No Teeth And Were Mostly Female!

The INAH said that skulls belong mostly to women, although they didn’t comment on why this was so. “We have recognized the skeletal remains of three infants, but most of the bones are from adults and, until now, they are more from women than from men.”

Obviously, the skulls were almost all toothless. While the experts are yet to establish whether the teeth were extracted in life or postmortem, precedents of this type have been recorded in the Chiapas region. In the 1980s, 124 toothless craniums, found in a cave in the municipality of La Trinitaria, were evaluated by the INAH. In 1993, Mexican and French explorers discovered five skulls placed in a wooden grid in another cave in the municipality of Ocozocoautla. These too deprived teeth.

Montes de Paz appeals to people to respect their archaeological heritage and immediately alert local authorities or the INAH when they stumble upon scenes that bore evidence of the remote past. Unsupervised visits by locals could affect the archaeological heritage, sometimes irreversibly. “The call is that when people locate a context that is likely to be archaeological, they avoid intervening and notify the local authorities or the INAH directly,” he said in the INAH press release.The INAH intends to continue exploring the Comalapa cave sacrifice scene. Perhaps some clues may be found to the puzzle of the toothless craniums. Answers to the mystery of why more women were sacrificed than men may also be forthcoming. Was it a reflection of power relations in the pre-Hispanic Chiapas society? Or were female human sacrifices more sacred than male?